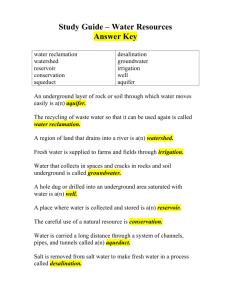

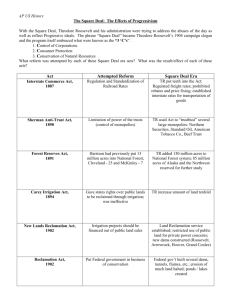

FWR 16 Reclamation Reform

advertisement