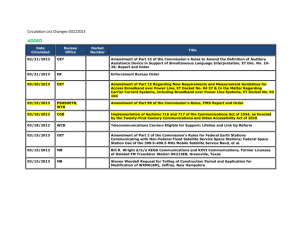

Physically Inaccessible FCC Final Order

advertisement