E. Bradford Burns, “The Poverty of Progress”

advertisement

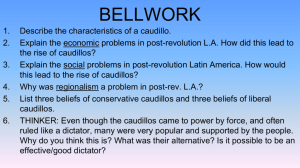

Leighton M. Quarles History 413 Poverty—Response In The Poverty of Progress, E. Bradford Burns does an admirable job of convincing this reader that modernization as realized in Latin America in the nineteenth century was highly undesirable and poorly implemented. Further, that implementation was conducted almost entirely by the creole elite, with precious little input from the “folk,” as Burns calls the mass of ordinary people. Indeed, modernization was in reality slavish imitation of European and AngloAmerican fashions, not genuine concern with raising the people’s standard of living. Problematically, Burns uses caudillos, regional strongmen who at one time or another dominated many Latin American countries, to show how things could have been done better. Native or mestizo caudillismo, as expressed by Burns, is the best of Latin American governmental arrangements in the nineteenth century. He demonstrates throughout that the Europeanized urban elite were sorry governors indeed. Nor did the answer lie in the rural patriarchy, which was a better mix of native and European but still overly idealized and hidebound. Worse, they were naïve beyond even the pipe-dreaming urban intellectuals. Luis Orrego Luco cut Chile’s patriarchal past to pieces with his story of Don Leonidas, a gentle, corrupt, avuncular bumpkin in uncharted waters.1 However, the “folk” maintained their own separate but more beneficial method of self-rule, by so-called “inorganic democracy,” which is to say that, in the words of Juan Batista Alberdi, the caudillos embodied “the will of the popular masses…the immediate organ and arm of the people…the caudillos are democracy.”2 The book is filled with evidence of European incompatibility with native values, as illustrated by the Generation of 1837 and their great influence on South American politics. It 1 E. Bradford Burns, The Poverty of Progress: Latin America In the Nineteenth Century (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1980), 84–85. 2 Ibid., 92. 2 almost escapes the reader’s notice that the Europeanization implemented all over Latin America was not just counter to native values; it was often counter to European standards as well. It is obvious that the supposed European values were a never-ending fad, not a legitimate value system. To Burns, the real, overarching issue was European/American incompatibility. Dependency theorist that he is, his primary yardstick for a government’s beneficence is whether it allowed foreign control of the economy. In showing that caudillos were bulwarks of antiimperialism, he discusses Juan Manuel de Rosas, who ruled Argentina from 1829 until his ouster by Brazilians in 1852. Rosas is highly controversial even today, not least because of the smear campaign perpetrated by his successors, including historian and President Domingo Sarmiento, the Generation of 1837’s most prominent intellectual. Though he “defied the Europeans…held a tight reign on the local elite, and enjoyed a genuine popularity among the masses,”3 Rosas also ruled through a feudalistic network of family members and cronies. Of this, Burns says only that “the identification of the masses with Rosas explains in part the role assigned that caudillo in official Argentine historiography.”4 While that is undoubtedly true, Burns hurts his credibility by focusing only on Rosas’ benefits to Argentina. One need only open Jacobo Timerman’s Prisoner Without A Name, Cell Without A Number to find an acid critique of caudillismo and the woeful ineffectiveness, corruption and instability of Argentine civil government. Burns’ revelation that countries ruled by caudillos maintained strong sovereignty shows that caudillismo could be a viable alternative to what the elites wished to label “democracy,” and is Burns’ trump card for any criticism of caudillos. The example of Paraguay, which was ruled by three successive caudillos from 1810 to 1870 until its overthrow by Brazilian, Argentine and Uruguayan forces, is the shining star for anti-Liberals. Not only does it satisfy reasonable 3 4 Ibid., 69. Ibid., 93. 3 requirements for “development,” it illustrates the zeal with which Liberal elites in other countries promoted their agendas. The three caudillos managed to confiscate the Church’s holdings, thus removing a major bone of contention that plagued other nations. They dispossessed the latifundia, and provided cheap land to all. Trade was conducted by the state, with the result that no merchant class ever developed. In fact, Paraguay built a steam navy and strung telegraph lines, all without incurring any foreign debt.5 As a reward for such innovation, Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay formed the Triple Alliance and crushed Paraguay, installing a suitable exportoriented elite government. The population’s great regard for their caudillo meant that the war took five years and wiped out ninety percent of Paraguay’s adult males.6 Ultimately, Burns’ notion of caudillismo as a more beneficial form of government than Europeanized Liberalism holds water, despite being a trifle idealistic. Dependency theorist or not, it is easy to see the advantages of national self-sufficiency. Burns’ continual evidence of the elites’ failure to do anything besides enrich themselves while bankrupting their countries strongly reinforces his argument, simply by promoting invidious comparisons with caudillismo. Moreover, Rosas’ inarguable popularity with the common people and the mute testimony of the dead in Paraguay support the claim that “inorganic democracy” was just that. 5 6 Ibid., 129. Ibid., 130.