Lecture: World Power Status

advertisement

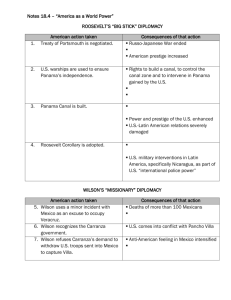

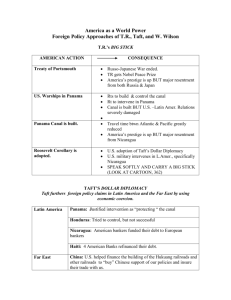

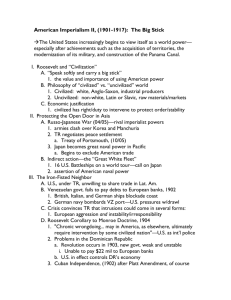

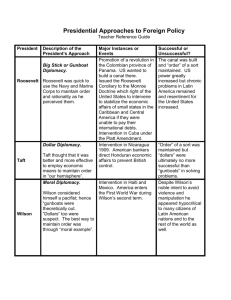

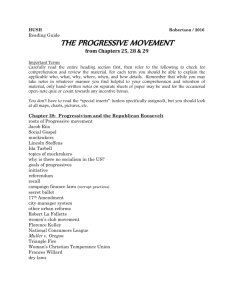

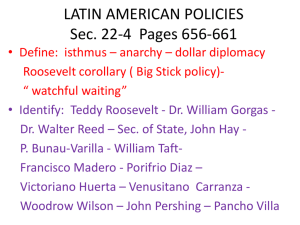

World Power Status The opening lines of the poem “The Second Coming,” by William Butler Yeats, have always seemed to me the best words in the English language to describe the 20th century as it dawned: Turning and turning in the widening gyre The falcon cannot hear the falconer; Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere The ceremony of innocence is drowned; The best lack all conviction, while the worst Are full of passionate intensity. The predictions of the isolationists were exactly right. Our sons did die in far-flung wastes of the world, but also in the seat of Western Civilization, Europe. The great crisis of the Great War should not have been the surprise nations claimed it to be. World-wide imperialism practiced by competing nations seems now a sure recipe for disastrous war. Into this drama stepped the United States of America, a hitherto isolationist power that had its “ceremony of innocence . . . drowned.” The painstaking process of managing world affairs began for the US in China, but on a “widening gyre” swept around the globe. There was no turning back after 1917 even though we tried. China had always been the hidden focus of American history. Remember, this whole hemisphere was discovered because Europeans were trying to find an easier route to the East, and even when colonized the search for a Northwest Passage continued for over a century. Exploration and colonization were tremendous accomplishments in and of themselves, but those who wanted an easy route to China considered them fruitless. With the Pacific coast in our possession, however, China was a jewel again. Trade with China made up 2% of all our foreign trade in 1900. China was why we wanted coaling stations across the Pacific Ocean that made us inclined toward imperialism in the first place. China was weakened by 1900 having lost a war with Japan in 1895. Germany, France, Russia, and Japan were carving out spheres of influence from this prostrate ancient giant, but Secretary of State John Hay sent a “note” to all the nations involved. The Open Door Note, as it came to be called, evoked from one historian the line, “With Hay’s Open-Door policy, the US jammed a foot into the fast-closing door of the East.” Well, I wasn’t really an historian when I wrote that line in an A. P. US history essay for Mr. Pickle, but he liked the line and read it aloud to the class. Maybe that’s why I became a history teacher. Hay’s Open-Door policy did warn the imperialistic powers of Europe and Asia (Sphere Nations) to leave room for the United States to carve out its own sphere. The Open Door Note contained three major provisions. First, Sphere Nations were to respect other nations’ spheres (including that of the US). Hay then said that the Chinese could still collect customs duties in all spheres (big of him to allow a sovereign nation to charge its own tariffs). Finally, China would charge the same customs duties for all nations (interesting that he would set the tariff rate for a foreign country). These and other presumptions on the part of foreign powers ignited the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. Anti-foreigner Chinese militants rioted and killed missionaries and representatives of foreign governments, including the German ambassador. All Sphere Nations sent military rescue missions to save their besieged personnel. The US sent 2,500 troops, and the combined foreign forces crushed the retaliating Chinese nationalists. Then Hay did another interesting thing; he pledged to maintain China’s sovereignty. That was big of him. As you might have guessed, these arrangements did not remain peaceful. The Russo-Japanese War broke out in 1904 over railroad rights across spheres in China. Just as the Japanese had beaten the larger nation of China, she was beating Russia when Theodore Roosevelt stepped in as mediator in 1905 and negotiated the Portsmouth Treaty, receiving emissaries from Japan and Russia aboard the Presidential Yacht. The Russians were much taller than the Japanese, but the Japanese walked away dominant. For ending the war (which was exhausting both countries and threatening to throw the whole region into turmoil), TR won the Nobel Peace Prize. TR’s own selection for Secretary of State, Elihu Root, further negotiated the Root-Takahira Agreement that allowed Japan and Russia (and the US) to divide influence in key areas, tacitly rewarding Japan for the sneak attack that nearly destroyed the Russian Navy. Watch for that strategy again around Dec. 7, 1941. Indeed, since the Root-Takahira Agreement excluded other Open Door Nations, historians say it launched Japan on an imperialist course that would one day include most of the Pacific Ocean and all of East Asia. China, meanwhile, had been destabilized to the point of the overthrow of the ancient imperial dynasty in a revolution in 1911. The United States bowed out of these conflicts gracefully, but not without becoming an Asian power and therefore a target. Theodore Roosevelt believed in a hands-on approach to foreign policy. Not only did he intervene personally in the Russo-Japanese War, but in the Moroccan Crisis. He embroiled the US in a conflict stemming from Germany’s occupation of North Africa when both the United Kingdom and France had already set their sights on carving out spheres there themselves. TR traveled to Algeciras, Spain, to personally direct a peace conference in 1906. The Algeciras Conference drew lines for all three European powers to share North Africa. This type of management of the world was most pronounced around the Caribbean Sea. TR was responsible for a new interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine called the Roosevelt Corollary. He said that since Europe cannot interfere in the Western Hemisphere, America would have to intervene in times of crisis. We did intervene, and before the 20th century was over we angered virtually every Latin American nation by either exerting economic dominance or by acting as an international police force or both. During TR’s presidency this activity centered on the Panama Canal. US investors took over the rights to dig a canal in Central America from the French who had failed because of yellow fever. American military doctors discovered the cause of malaria as well as ways to combat it, plus lobbying in Congress changed the route from the country of Nicaragua to the Isthmus of Panama. The only problem was that Panama belonged to Colombia who wouldn’t negotiate with the US, so TR aided the Panamanian Revolution. In return, newly independent Panama gave the US a 6-mile-wide Canal Zone (for $10 million and a $250,000/year lease). Construction of the Canal remains one of the greatest civil engineering feats of human history. It took seven years and $400 million to move 211 million cubic yards of dirt out of the way, and did you know the Canal goes up and then down again? The Panama Canal was not merely a ditch dug all the way across. Congress was alarmed at TR’s use of presidential power, but TR famously said, “While Congress debated me, I dug the Canal.” Some historians claim that this feat is Theodore Roosevelt’s greatest contribution to mankind. Obviously, TR believed in the president’s duty to personally manage foreign policy, and every president since has had to at least appear to do so. TR spoke of noble duties while providing for the economic realities of big business expansion. American presidents have ever since had to balance humanitarian stances with America’s “interests” abroad. TR both busted trusts and cooperated with them. All the while he spoke in regard to foreign policy with his famous, borrowed African proverb, “Speak softly and carry a big stick . . . .” He used the “bully pulpit” to make pronouncements to other countries as well as to Americans, and he backed up his assertions largely with the United States Navy. In fact, TR had sixteen of the newest US battleships painted white and sent them to circumnavigate the globe, stopping at all major ports along the way. The Great White Fleet accomplished this feat in 1907, and our friends and enemies all realized we could project our power anywhere in the world. The fleet was TR’s Big Stick, and when it returned it went immediately into dry dock and was painted grey again in order to be able to pounce upon enemies out of the fog. William Howard Taft had yet another innovation on the Monroe Doctrine. He said that the US needed to “subordinate idealistic humanitarian sentiments to the dictates of sound policy and strategy, and to legitimate commercial aims.” In other words, the American government was going to allow American investment dollars to go to cooperative countries and cut off the supply to countries that opposed American policy, just as if the president had a spigot to either turn off the flow of dollars or let them pour out. Taft’s innovation has been our chief method of foreign intervention ever since, and it is known as Dollar Diplomacy. Nicaragua, Guatemala, Honduras, and Haiti were the biggest recipients of US investment dollars under Taft. President Taft believed Dollar Diplomacy would work with international arbitration to spare the US from involvement in the growing animosity in Europe. Woodrow Wilson and his Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan, agreed. The egotism of these men along with their noble intentions resulted in American intervention in foreign affairs, and eventually the US had to apply force despite Bryan’s anti-imperialism. By 1914, just prior to World War I, the world believed a new age of international harmony was at hand—PEACE ON EARTH! The “melting pot” of America was going to lead the way to a worldwide brotherhood of man, and arbitration was the solution. The International Court was begun in the Netherlands in 1899, and its mission has been that of major beauty queens throughout the 20th century—world peace. Even Woodrow Wilson publicly predicted peace within weeks of the outbreak of World War I. On the Fourth of July in 1914 he said in a speech My dream is that as the years go on and the world knows more and more of America, it will turn to America for those moral inspirations which lie at the basis of all freedoms . . . and that America will come into the full light of day when all shall know that she puts human rights above all other rights and that her flag is the flag not only of America but of humanity. Meanwhile Wilson intervened in Latin America more than TR or Taft. He sent the military into Haiti in 1915, American investment dollars and the Marines into the Dominican Republic in 1916, and both into Cuba in 1917. Mexico proved his complete confidence to take Progressivism to the international level and to solve problems that other nations “could not” solve for themselves. The dictator of Mexico, Porfirio Diaz, was overthrown by Francisco Madero in 1911 while Taft was president. Taft recognized the new government, but a counterrevolution ousted and assassinated Madero in a coup led by Victoriano Huerta. Wilson denounced Huerta as a murderer and “picked” Venustiano Carranza to stabilize Mexico for US investment dollars, especially in an oil industry, but also for democracy. By the way, there is nothing in the US Constitution about the president picking the leaders of foreign countries. Tension escalated when Mexico arrested some US sailors. Wilson demanded an apology but received none. He ordered the US Army to occupy Vera Cruz, which is a polite way of saying he ordered the invasion Mexico. Huerta resigned and Carranza took power, but just like Emilio Aguinaldo in the Philippines, Carranza wanted US forces out of Mexico. Wilson and Carranza turned to the new miracle cure, international arbitration. The “ABC Powers” (Argentina, Brazil, and Chile) were asked to arbitrate a settlement. Before a solution could be worked out, however, Pancho Villa rose up to challenge Carranza and in the process killed 16 US citizens. Before Wilson could react, Villa killed 19 more US Citizens. Then Wilson sent John J. Pershing (the future commander of US forces in World War I) to bring Pancho Villa to justice. Carranza decried another invasion of Mexico. Did you know the US almost had another Mexican War? Perhaps the only reason we did not is that the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir of the thrones of Austria-Hungary, was assassinated in Serbia on June 28, 1914.