Revision Unit 3

advertisement

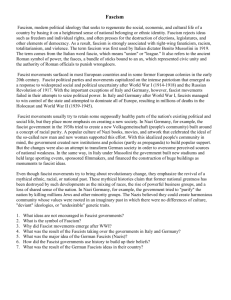

The Appeal of Fascism General The Fascist movement held an appeal to Italians of various classes in the troubled post -war period. In contrast to what seemed to be a weak and indecisive liberal government, Fascism seemed strong and assertive; its uniforms, parades and marches served to reinforced this image. In the wake of the mutilated victory, Fascism promised to make Italy great again on the international stage. Perhaps, most of all, Fascism seemed to be the only force prepared to resist the advance of socialism in the turbulent years of the ‘Bienno Rosso’. Fascist violence gained acceptance because of this and also served to intimidate any potential critics or opponents. It reinforced the image of Fascism as a force for action and change, something that served to attract support from the young. Social Groups While Fascism held a general appeal, it gained particularly strong support from certain social groups. A key group of supporters came from the petty bourgeoisie, or lower middle classes, who felt threatened by the advance of socialism both in the towns and the countryside but felt that their interest were ignored by the liberal government. Many were disgruntled ex-soldiers who looked for a better life after what they consider to be a victorious war. Landowners and industrialists were prepared to back a movement that seemed to take a much stronger stand than the government in the face of socialist agitation. Even certain groups of workers and peasants were attracted to Fascism because of its early revolutionary syndicalism and its promise to create a classless society. Mussolini’s Concessions Mussolini helped to widen the base of support for Fascism by dropping some of its more radical policies such as its anti-capitalist socialism, anti-republicanism and anticlericalism. Such concessions enabled the conservative elite to accept Fascism and, in turn, Mussolini showed that he was willing to enter parliament and worked from within the constitution. Increasingly the emphasis was placed on nationalism, an active foreign policy and a strong state. The last of these was welcomed by many in the face of the threat of socialist revolution that seemed very real during the years of the ‘Bienno Rosso’. Weakness of Opposition The Government Support for the Italian government was precarious enough in 1914 but the ‘mutilated victory’ of 1919 and post-war problems such as inflation and unemployment weakened the government even further. A series of short-lived minority coalitions were the result of the introduction of proportional representation and the inability of the two major parties ( the PSI and PPI ) to cooperate. Even within the two major parties there were further divisions that exacerbated the situation and which impaired their ability to present a united front in opposition to the fascist threat as it emerged in 1921-2. Giolitti’s misplaced attempt to bring the Fascists into the government in the spirit of ‘transformismo’ politics further served to emphasise the impotence of Liberal Italy. The Socialists Although the Socialists seemed to be the strongest force in Italian politics both before and after World War One, they suffered from a number of weaknesses. The political wing of the movement, the PSI, was split into three factions: the minimalists urging reform through parliament, the maximalists urging revolution and the communists who urged an even more radical revolution along Leninist lines. At the ‘shop-floor’ level, socialism was also divided into Chambers of Labour, Socialist Leagues and more conservative Catholic Unions. Perhaps most significant was the lack of a leader or leadership that was strong enough to bridge these divisions and challenge the rise of Fascism; the PSI failed to agree to a coherent strategy. Moreover, in the turbulent years of the ‘Bienno Rosso’, socialism frightened many Italians, as a repeat of the Bolshevik revolution in Russia seemed all too real. Many patriots and ex-soldiers already felt resentful of the socialists’ opposition or neutrality towards the war and the way in which many socialist workers had ‘shirked’ their responsibility to fight. The March on Rome The reasons for the success of the March on Rome and Mussolini’s appointment as Prime Minister can be largely attributed to perceptions of both the Fascist threat and Fascist promise held by those in power in 1922. The successful agitation of the Fascist ‘squadristi’ led by the so-called ‘ras’ in the provinces did much to develop mass support for Fascism but also did much to create the threat of a Fascist revolution or coup. The seizure of provincial cities was vital in creating the exaggerated threat of the march on the capital in 1922. Although Mussolini himself showed little confidence in staying in Milan and preparing to flee to Switzerland, politicians such as Facta, Salandra and Giolitti showed little firmness either. This did little to encourage King Victor Emmanuel who pulled back from his initial decision to impose martial law and ask the army to oppose the anticipated Fascist advance. The king’s eventual decision to invite Mussolini to become Prime Minister, on the advice of Salandra, was influenced by number of factors. The fact that there was some support and sympathy for the Fascists among the armed forces made the King doubt their ability to resist the march. In the event of stern resistance, the king feared the spectre of civil war: in the event of Fascist success, he feared his own replacement by his pro-Fascist cousin, the Duke of Aosta. Like many members of the elite and even Pope Pius XI, the King was disillusioned with the weak liberal government and looked to Mussolini for a stronger leadership in the face of a socialist threat that by 1922 was more apparent than real. In a coalition ministry, it was hoped that the more moderate Mussolini could be tamed further.