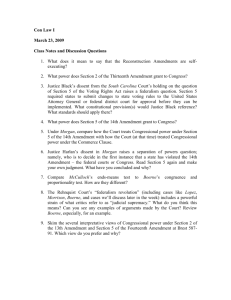

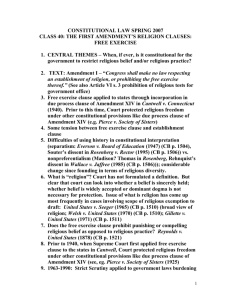

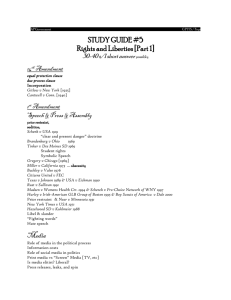

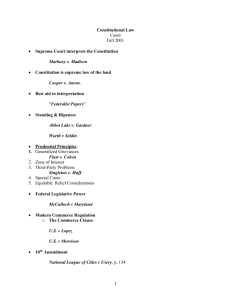

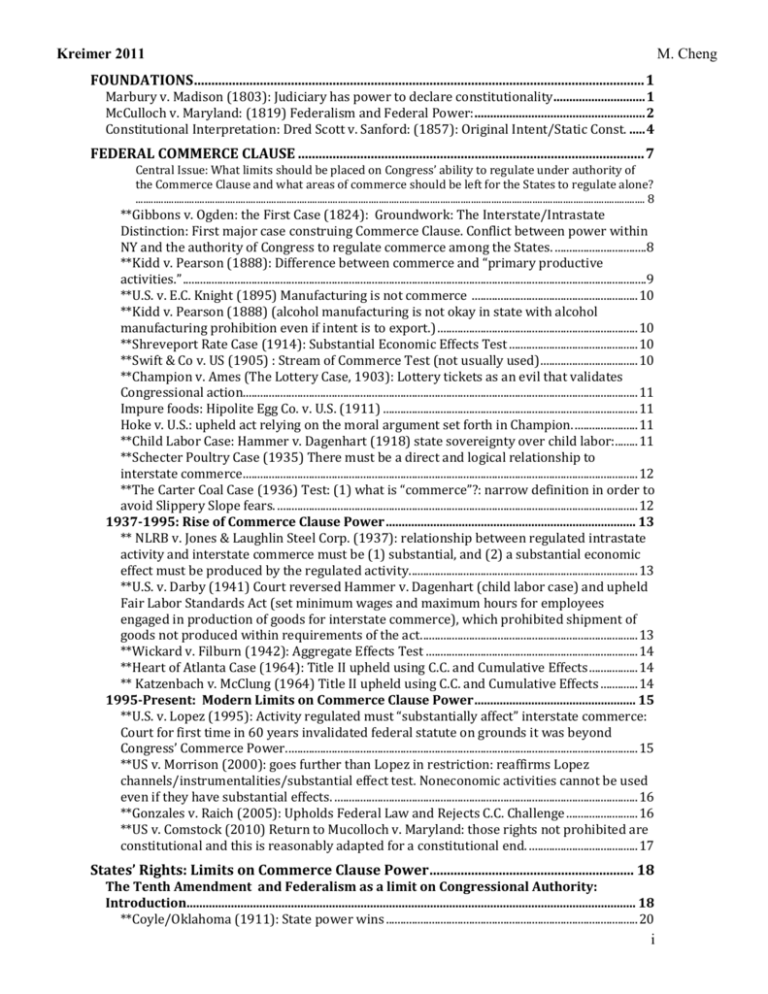

Marbury v - Penn APALSA

advertisement