Case 4.14

advertisement

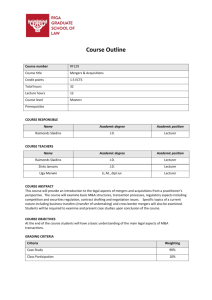

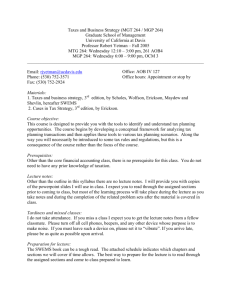

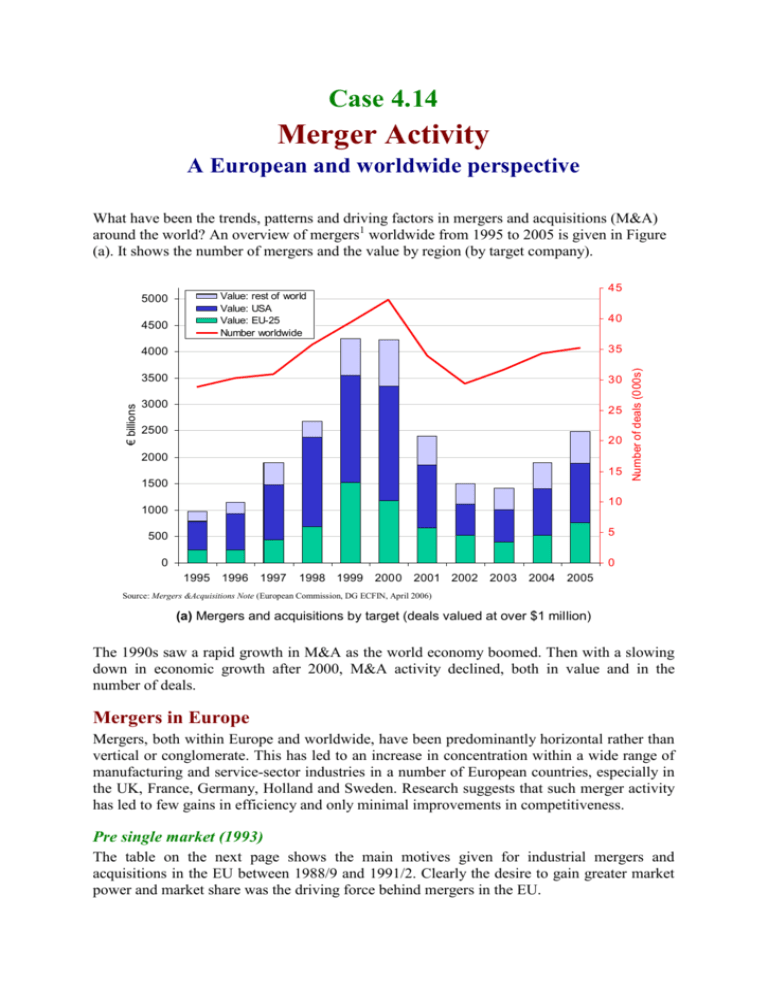

Case 4.14 Merger Activity A European and worldwide perspective What have been the trends, patterns and driving factors in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) around the world? An overview of mergers1 worldwide from 1995 to 2005 is given in Figure (a). It shows the number of mergers and the value by region (by target company). 40 4000 35 3500 30 3000 25 2500 20 2000 15 1500 Number of deals (000s) 4500 € billions 45 Value: rest of world Value: USA Value: EU-25 Number worldwide 5000 10 1000 500 5 0 0 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Source: Mergers &Acquisitions Note (European Commission, DG ECFIN, April 2006) (a) Mergers and acquisitions by target (deals valued at over $1 million) The 1990s saw a rapid growth in M&A as the world economy boomed. Then with a slowing down in economic growth after 2000, M&A activity declined, both in value and in the number of deals. Mergers in Europe Mergers, both within Europe and worldwide, have been predominantly horizontal rather than vertical or conglomerate. This has led to an increase in concentration within a wide range of manufacturing and service-sector industries in a number of European countries, especially in the UK, France, Germany, Holland and Sweden. Research suggests that such merger activity has led to few gains in efficiency and only minimal improvements in competitiveness. Pre single market (1993) The table on the next page shows the main motives given for industrial mergers and acquisitions in the EU between 1988/9 and 1991/2. Clearly the desire to gain greater market power and market share was the driving force behind mergers in the EU. Main motives for mergers and joint ventures in the EC: 1988/9–1991/2 Strengthening of market position Expansion Restructuring (including rationalisation and synergy) Complementarity Diversification Co-operation Research and development Other Total cases specifying reasons 648 419 158 72 55 13 3 73 1441 Source: Reports on Competition Policy (Commission of the European Communities, various years). For most of the 1980s, the majority of mergers occurring in Europe were within national boundaries. But as inter-EU trade grew and as Europe was increasingly seen by business as a ‘single market’, so an increasing proportion of mergers were ‘cross-border’. The proportion of total EU mergers that were between companies in different member states grew from 8.3 per cent in 1987/8 to 20.5 per cent in 1992/3. An important factor explaining the increase in inter-EU mergers was the process of dismantling barriers to trade to create a true ‘common market’ by 1993 (see section 11.5). Firms took the opportunity to establish a European network and restructure their operations as well as to expand productive capacity. A notable feature of European merger activity was the large size of many of the firms involved. The larger the firms, the more likely they are to be involved in cross-border mergers rather than purely domestic ones. The implication of these trends is that markets are becoming increasingly concentrated. Since 1993 When the single market came into being in January 1993, many commentators predicted that there would be a new wave of merger activity as companies, faced with new competition, would be forced to rationalise, or would take the opportunity to expand their operations in other EU countries. As it turned out, the recession gripping Europe caused merger activity initially to decline (see the diagram). The main determinant of merger activity in the short run remains the overall state of the economy. When an economy moves into recession, so merger activity also declines. After 1994 the growth in mergers in the EU resumed. There were several explanations for this: A recovery in growth throughout the EU. A growing process of ‘globalisation’. With the dismantling of trade barriers around the world and increasing financial deregulation, so international competition has increased. Companies have felt the need to become bigger in order to compete more effectively. Falling interest rates, making investment in the stock-market more attractive than saving in a bank. A deepening of the single market, making Europe-wide operation by companies easier. An increasing conviction that there would be a successful move to a single currency, making it easier for companies to operate on an EU-wide basis. 2 As 1999 approached, and with it the arrival of the euro, so merger activity reached fever 1000 18000 900 EU/non-EU 800 Inter-EU 14000 Total number of mergers 12000 € billions 600 10000 500 8000 400 Number of deals 700 16000 6000 300 200 4000 100 2000 0 0 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 Source: European Economy, Supplement A , No 12 - December 2001 (European Commission): based on Table 1 and Graphs 7 and 10 (b) Mergers and acquisitions involving an EU company pitch, stimulated also by the strong growth experienced throughout the EU (see Figure (b)). Then, with the worldwide economic slowdown in 2001, there was a fall in all types of merger in the EU: between companies in a single EU country, in two or more EU countries, and in an EU and a non-EU country. Mergers worldwide The 1990s The early years of the 1990s saw relatively low M&A activity as the world was in recession, but as world economic growth picked up, so world-wide M&A activity increased. Economic growth was particularly rapid in the USA, which became the major target for acquisitions. There was also an acceleration in the process of ‘globalisation’. With the dismantling of trade barriers around the world and increasing financial deregulation, so international competition increased. Companies felt the need to become bigger in order to compete more effectively. By the end of the 1990s, annual worldwide M&A activity was three times the level of the beginning of the decade. At this time there were some very large mergers indeed. These included a €29.4 billion marriage of pharmaceutical companies Zeneca of the UK and Astra of Sweden in 1998, a €205 billion takeover of telecoms giant Mannesmann of Germany by Vodafone of the UK in 1999 and a €50.8 billion takeover of Orange of the UK by France Telecom in 2000. Other sectors in which merger activity was rife included financial services and the privatised utilities sector. In the UK, in particular, most of the privatised water and electricity 3 companies were been taken over, with buyers attracted by the sector’s monopoly profits. French and US buyers were prominent. The early 2000s Then, with a worldwide economic slowdown after 2000, there was a fall in both the number and value of mergers throughout most of the world. What is more, the worldwide pattern of M&A activity was changing. Increasingly both European and US companies were looking to other parts of the world to expand their activities. This is illustrated in Figure (c). 60 1990-3 Percentage of total 50 2000-3 40 30 20 10 0 N. America EU-15 Rest of Europe Asia Rest of world Source: Mergers &Acquisitions Note (European Commission, DG ECFIN, October 2004) (c) Mergers and acquisitions by target region (% of total number) The two major target regions have been (a) the rest of Europe, especially the ten countries joining the EU in 2004 plus Russia, and (b) Asian countries, especially India and China. These new markets have the twin attractions of rapidly growing demand and low costs, including cheap skilled labour and low tax rates. Companies from the EU-15 countries have focused especially on the rest of Europe, with a 65 per cent share of inward M&A in this region between 2000 and 2003. By contrast, the EU-15 countries had only a 17 per cent share of inward M&A in Asia, compared with a 29 per cent share for North America and 47 per cent share for Asia itself. The small share of inward investment in Asia by EU companies is worrying for EU ministers, given that China and India are the world’s two fastest growing markets. Those companies which have already invested in these countries are likely to have gained a ‘firstmover’ advantage through establishing sources of supply and building relationships. 4 Inter-EU € 2001 1999 1998 1997 1996 1995 1994 1993 1992 1991 1000 900 800 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 Number 18000 16000 14000 12000 10000 8000 6000 4000 2000 0 EU/nonTotal billionsof deals of EU number mergers Types of M&A activity Many M&A deals are ‘hostile’. In other words, the company being taken over does not want to be. The deals are often concluded after prolonged boardroom battles, with bosses of the acquiring company seeking opportunities to build empires, and bosses of the target company attempting all sorts of manoeuvres to avoid being taken over. This may involve them seeking deals with alternative, more ‘friendly’ companies. Generally companies are increasingly using the services of investment banks to help them in the process of making or warding off deals. Despite the growing number of horizontal mergers, there has also been a tendency for companies to become more focused, by selling off parts of their business which are not seen as ‘core activities’. For example, not long after its takeover of Wellcome, Glaxo decided to concentrate on the production of prescription drugs, and as a consequence to sell its share of Warner Wellcome, which produced non-prescription drugs. Another example was Volvo. After unsuccessfully attempting to merge with Renault in 1993, it subsequently divested itself of several companies that it owned in a variety of industries, ranging from banking and finance to food, matches and pharmaceuticals. This trend of horizontal mergers and conglomerate and vertical de-mergers has allowed companies to increase their market power in those specific sectors where they have expertise. Consumers may gain from lower costs, but the motives of the companies are largely to gain increased market power – something of dubious benefit to consumers. Question Are the motives for merger likely to be different in a recession from in a period of rapid economic growth? 1 When we refer to ‘mergers’ this also includes acquisitions (i.e. takeovers). 5