Document

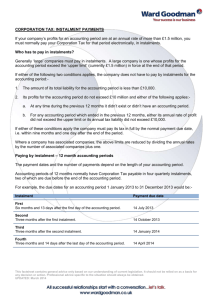

advertisement