RaveretRichter_EcologyFood_SAEM_2005

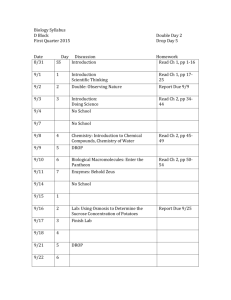

advertisement

Monday 1010-1310 Dana 381 Wednesday and Friday 10:10-11:30 Dana 381 and field trips Raveret Richter Fall 2005 BI 115H Ecology of Food “Tell me what you eat and I will tell you what you are.” Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin Ecology is the study of interactions among organisms and between organisms and their environment. Ecologists observe the patterns characterizing the distribution and abundance of organisms and try to understand the phenomena influencing these patterns in nature. Working from a who-eats-whom perspective, this course addresses central concepts in behavioral ecology, population ecology, community ecology and ecosystem ecology by investigating what organisms eat and how they procure it, how organisms avoid becoming food, and why these arrangements persist in nature. We will also analyze the ecology of landscapes and resources harvested by humans. The study of interactions among organisms in pursuit of food illuminates the fundamental interactions, patterns and processes at the heart of the science of ecology, provides insight into the immense ecological ramifications of human production and harvest of food resources, and even suggests ecological correlates of world cuisine. In the spirit of both the Honors Forum and the Environmental Studies program (this biology course is affiliated with both), we will take on complex issues, and work to understand the rationales for prevailing (and quite often conflicting) arguments regarding how the ecological world works. As often as possible, we will review the actual data on which the arguments are based. Readings and analyses will be abundant, challenging, and absolutely essential components of your course experience. Sources will range from scientific literature in research journals through journalists’ renditions of scientific arguments. You will thus acquire both a grasp of the science and a sense for its broader applications and significance. Since many of us learn by doing (or, as my mother used to put it, “Monica, you always have to learn everything the hard way!”), we won’t just talk about food, we will often eat it. Our studies of herbivory and plant defenses will include discussions of theoretical perspectives, prediction and measurement of patterns of herbivory on North Woods plants, and some salad bowl science as we sample and discuss the physical and biochemical attributes of fall harvest offerings from the Saratoga Farmers Market. Another problem that we will address is how plants, which are sedentary, disperse their progeny in the environment. As we consider and consume the enticements of various fruits, we will distil important principles of seed dispersal. We will take field trips to several local farms to observe firsthand the inputs, outputs and ecological underpinnings of human food production and to evaluate the biodiversity impacts of different sorts of agricultural practices. Throughout the course, we will consider the behavioral ecology of food choice; our perspectives will range from those of honey bees and caterpillars through those of birds and chefs. You will also complete a research project in which you perform a detailed investigation of the physical attributes and ecology of a particular food. Why is it sought as food, and what attributes make it desirable or difficult to utilize? How is it processed for consumption, and why? Is it cultivated or does it grow in the wild? How does utilization of this food influence its population biology? How does cultivation and/or harvest of this organism impact populations of other organisms (remember those food webs!) What roles does this organism serve in the cultures that exploit it as a food resource? After this exploration, you will find it hard to take food for granted. As I write this, my entire study is literally buried in books and articles about food and ecology, and each source that I read points me to several more. A complex web connects the banana on your breakfast cereal to tropical ecology, sociology, economics, and politics, McDonald’s French fries have forever changed the ecology and the essence of the potato, and fisheries have altered entire marine food webs. These relationships are complex (Whooo, boy are they — researching broadly and then successfully distilling the essence is critical, or you will be overwhelmed!), fascinating, and quite often unsettling. I expect that you will find this challenge intellectually engaging and fun: food is central to all life, and there will be many weird twists and surprises as we study its ecology. In addition, this broad-based examination of the ecology food is likely to influence your personal perspectives on and choices of food. So that we all have a chance to learn about what each of you found in the course of your research, you will share your findings with your classmates in an oral presentation. If ecologically and logistically reasonable to do so, you will also share an edible sample of your research subject with the class. An analytical research paper will serve as written documentation of your research. PROFESSOR: Dr. Monica Raveret Richter, office/lab: Dana 370/378 Office hours: Wednesday 11:30-12:45 Friday 11:30-12:45 and by appointment My email address is: mrichter@skidmore.edu. This is the best way to reach me during the day before 1400 hrs. My office/lab extension is 5083; my home phone number is 587-3574. If you choose to reach me by phone, try my office/lab extension first. You can also call me at home (before 8:00 PM) to ask questions or set up appointments. I encourage you to drop in and visit with me during office hours, or to make an appointment to visit. I’m always interested in talking about ecology and food (or conducting ecological research, or eating food…), and I would be happy to answer any questions that you might have about course material, or to help you explore topics in greater depth. COURSE STRUCTURE: •Lectures/discussions meet from 1010-1130 hrs Wednesday and Friday in Dana 381. •Laboratories usually meet from 1010-1310 hrs Monday in Dana 381 or in the field; there are also weekend field laboratories. Labs will provide a chance for you to observe what we are talking about in lecture, to test ideas experimentally, and to develop your quantitative skills. We will have several outdoor labs. For these labs, wear comfortable walking shoes (something that can get muddy) and outdoor clothing that provides mosquito and tickprotection and is appropriate for the weather. Recommended clothing: light colored long pants, long-sleeved shirts and, if you wish, a hat. •Discussions will take place throughout the semester. In discussions, we will explore and evaluate supplementary readings and ideas related to lecture topics. •Readings: Assigned readings are listed in the syllabus. Copies of the readings can be borrowed from the file outside of Dana 381 for two hours. Additional readings may be assigned throughout the semester. Students are responsible for keeping up with reading assignments (read them BEFORE class!) and will be responsible on examinations for material covered in the readings. •Course grades will be awarded as indicated below: Food ecology research project: Proposal 2% Presentation 6% Research paper 12% Exams (2 lecture exams + final exam) 50% Best exam score: 20% Other 2 exam scores: 15% each Labs (including data collection, analysis, 25% written and oral reports) Discussion, participation, preparation 5% I do not plan make-up sessions for missed discussions or laboratories. If you miss discussion or laboratory, your grade will be adversely affected. Exams Exams are based on material that we cover in lectures, discussions, and readings. I expect you to demonstrate your mastery of factual material, your ability to argue a point of view on controversial topics (examples from lecture, discussions and assigned readings will be useful), and your ability to synthesize material and apply it to new situations. Exams are to be completed without consulting with your notes, texts, or fellow students during the test unless I give explicit directions otherwise. For example, on a take home essay, I might permit the use of notes and literature. Collaboration and attribution of materials: Much scientific work is done as collaboration, and in this course you will often work in groups to solve problems. I expect, however, that all written material you hand in to me will reflect your own original thought and synthesis. For example, I encourage lab groups to work together to analyze data. If there are questions to answer at the end of a lab, you should feel free to discuss these questions with one another. However, the answers that each of you hand to me should be written individually and should in no case be copied verbatim from other students in your lab group. Similarly, when you are writing research reports for group projects, I encourage you to share, with other members of your group, any useful references that you have found. You should feel free to discuss these references together, and to consider how they bear upon your research topic. However, when you are writing your report, I expect each of you to construct your own original arguments. You should work independently when you write the introduction and discussion for your reports; group authorship is not acceptable. I want to make sure that each of you develops strong critical writing skills. In order to best develop these skills, you must do your own writing. You will often need to draw upon the work of others to support your arguments. Always acknowledge the sources of material that you use in your writing. You must cite the sources of ideas, factual material, and quotations; failure to do this constitutes plagiarism. Citations should follow the format used in recent issues of the journal Ecology. Your handout “Citation Guidelines” illustrates the correct format for citing a variety of sources. You are responsible for adhering to these guidelines for collaboration and attribution of material. If you have any questions about this, please bring in your work-in-progress, and we can discuss how to apply these guidelines to specific situations. Failure to follow these procedures will result in a grade of zero for the assignment or exam, and violations of academic integrity will be reported to the Dean of Studies. TENTATIVE COURSE SYLLABUS DATE TOPIC READING ASSIGNMENTS (Read these BEFORE class!) WEEK 1 7 Sep Ecology and food: An introduction Stiling, P. 2002. Why and how to study ecology. Pages 2-18 in Ecology: theories and applications. Prentice Hall, New Jersey, USA. Owen, J. 1980. Food and feeding. Pages 922 in Feeding strategy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois, USA. 9 Sep Scientific inquiry: A critical approach Dawkins, R. C. 1998. Unweaving the uncanny. Pages 145-179 in Unweaving the rainbow: science, delusion and the appetite for wonder. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. Dayton, P. K. 1998. Reversal of the burden of proof in fisheries management. Science 279: 821-822. Townsend, C. R, M. Begon and J. L. Harper. 2003. Ecology and how to do it. Pages 337 in Essentials of ecology. Second edition. Blackwell Publishing, Massachusetts, USA. 11 Sep (Sunday) LAB 3-Corner Field Farm Field Trip Leave Dana parking lot at 8:00 AM (Sorry, the sheep can’t hold their milk any longer!). Return to Skidmore at approximately 12:00 noon. Dress for the weather. Bring water and use sun protection if it is a hot day. Wear shoes or boots that can be dipped in a vat of disinfectant and scrubbed as you enter and exit the farm. This is not a good place for sandal WEEK 2 14 Sep 16 Sep Robinson, J. 2004. Imagine; Back to basics. Pages 9-17 in Pasture perfect: the farreaching benefits of choosing meat, eggs and dairy products from grass-fed animals. Vashon Island Press, Vashon, Washington, USA. Find information about the farm at http://www.dairysheepfarm.com/ If time permits, we will make a quick stop at the Sheldon Farms farm stand on the return trip to Skidmore. You can peruse their offerings and, if you wish, purchase fresh, locally grown produce, cheese, maple syrup and other foods. Scientific inquiry: case studies in foraging Gould, J.L. & Gould, C.G. 1988. Discovery of the dance language; dance communication. Pages 55-65 in The honey bee. Scientific American Library, New York, New York, USA. An evolutionary perspective on foraging: Darwin’s thesis and the evidence Solomon, E. P., L. R. Berg, and D. W. Martin. 1999. Introduction to Darwinian evolution. Pages 370-388 in Biology. Fifth edition. Saunders College Publishing, Philadelphia, USA. Gould, S. J. 1983. Evolution as fact and theory. Pages 253-262 in Hen’s teeth and horse’s toes. W. W. Norton and Company, New York, New York, USA. WEEK 3 19 Sep LAB Honey bee foraging: Experimental design Barth, F. 1985. Visual signposts on the flower. Pages 116-122 in Insects and flowers: the biology of a partnership. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, USA. Gould, J. L. and C. G. Gould. 1988. The life of the bee. Pages 19-44 in The honey bee. Scientific American Library, New York, New York, USA. Raveret Richter, M. A. and J. M. Keramaty.* 2003. Honey bee foraging behavior. Pages 133-143 in Exploring animal behavior in laboratory and field. Academic Press, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. Wanna dance? 21 Sep Adaptation and natural selection: Case studies in foraging *(a.k.a. Dr. J. M. Keramaty DVM, Jasmin collaborated in researching this material, presenting it as a demonstration laboratory at the Animal Behaviour Society’s annual meeting, and preparing it for publication, all when she was a Skidmore undergraduate.) Weiner, J. 1995. A special providence. Pages 70-82 in The beak of the finch. Vintage Books of Random House, New York, USA. Boag, P. T. and P. R. Grant. 1981. Intense natural selection in a population of Darwin’s finches (Geospizinae) in the Galapagos. Science 214: 82-85. 23 Sep Populations: Demographic patterns and processes Ehrlich, P. R. and A. H. Ehrlich. 1990. Why isn’t everyone as scared as we are? Pages 13-23 in The population explosion. Simon and Schuster, New York, USA. Raven, P. H. and G. B. Johnson. 2002. Population ecology. Pages 495-514 in: Biology. McGraw Hill, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. WEEK 4 26 Sep LAB Honey bee foraging: Field experiments Opportunity to volunteer (or, splurge and attend the benefit as a guest): Through Farmers’ Hands—A Country Prom Monday, September 26, 6:00 to 10:00 pm Canfield Casino, Saratoga Springs, NY A celebration of our region’s farms and food, set to the tune of new and old country music, presented in an elegant 19th century ballroom, to benefit the Regional Farm & Food Project. 28 Sep Predation I: Adaptations for defense Forsyth, A. and K. Miyata. 1984. Jerry’s maggot. Pages 153-167. in Tropical nature. Scribner, New York, USA. Owen, D. 1980. Warning coloration, mimicry. Pages 105-125 in Camouflage and mimicry. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois, USA. Recommended: Plumwood, V. 2000. Being prey. Utne Reader 100: 56-61. 30 Sep Predation II: Trophic cascades, marine food webs, and human consumption of marine resources. Estes, J. A., M. T. Tinker, T. M. Williams and D. F. Doak. 1998. Killer whale predation on sea otters linking oceanic and nearshore ecosystems. Science 282: 473-476. Naylor, R. L., R. J. Goldburg, J. H. Primavera, N. Kautsky, M. C. M. Beveridge, J. Clay, C. Folke, J. Lubchenco, H. Mooney and M. Troell. 2000. Effect of aquaculture on world fish supplies. Nature 405: 1017-1024. Williams, N. 1998. Overfishing disrupts entire ecosystems. Science 279: 809. WEEK 5 3 Oct 5 Oct LAB Herbivory and adaptations for defense I: Milkweed field lab Dussourd, D. 1990. The vein drain; or, how insects outsmart plants. Natural History 99(2): 44-49. Field trip: Skidmore campus •Dress for the weather. Wear light colored clothing (long pants and long sleeves; insect protection). Wear sturdy shoes. •Meet at 10:00 in the lab, Dana 381. Recommended Dussourd, D. E. 1993. Foraging with finesse: Caterpillar adaptations for circumventing plant defenses. Pages 92131 in N. E. Stamp and T. E. Casey, editors. Caterpillars: ecological and evolutionary constraints on foraging. Chapman and Hall, New York, New York, USA. Herbivory Hairston, N. G., F. E. Smith and L. B. Slobodkin. 1960. Community structure, population control and competition. American Naturalist 94: 421-425. What color is the world? Why? Stiling, P. 2002. Herbivory. Pages 170-188 in Ecology: theory and applications. Prentice Hall, New Jersey, USA. 7 Oct Exam 1 (through ecology of marine resources) WEEK 6 11 Oct LAB Herbivory and adaptations for defense II. Herbivore food choice and evolution of plant defenses: Observations and analyses in the North Woods and the salad bowl. Field trip: Skidmore campus •Dress for the weather. Wear light colored clothing (long pants and long sleeves; insect protection). Wear sturdy shoes. •Meet at 10:10 in the lab, Dana 381. 12 Oct Parasites and pathogens; the evolution of virulence. Fisher, M. 2003. Want herbal remedies? Look to your salad. University of Wisconsin-Madison College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Quarterly 21(1): 2. Ogorzaly, M. C. 2001. Spices, herbs and perfumes. Pages 192-217 in Economic botany: plants in our world. Third edition. McGraw-Hill Higher Education, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. Ewald, P. W. 1993. The evolution of virulence. Scientific American 268:86-88, 90-93. Smith, R. L. and T. M. Smith. 2003. Parasitism and mutualism. Pages 309-328 in Elements of ecology. Benjamin Cummings, San Francisco, California, USA. Recommended Hooper, J. 1999. A new germ theory. The Atlantic Monthly 283(2): 41-53. 14 Oct WEEK 7 17 Oct Population size and species interactions Jones, C. G., R. S. Ostfeld., M. P Richard. E. M. Schauber and J. O. Wolff. 2002. Chain reactions linking acorns to gypsy moth outbreaks and Lyme disease. Science 279: 1023-1026. LAB Data analysis and writing workshop 19 Oct Mutualism 21 Oct STUDY DAY No class meeting Smith, R. L. and T. M. Smith. 2003. Parasitism and mutualism. Pages 309-328 in Elements of ecology. Benjamin Cummings, San Francisco, California, USA. WEEK 8 24 Oct LAB Seed dispersal (Or, how fruits have their way with us) “Well, I’ll eat it,” said Alice, “and if it makes me grow larger, I can reach the key; and if it makes me grow smaller, I can creep under the door: so either way I’ll get into the garden, and I don’t care which happens!” —Lewis Carroll Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Forsyth, A. & Miyata, K. 1985. Eat me. Pages 77-87 in Tropical nature. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, New York, USA. Recommended This reinforces ideas in the required reading, and has gorgeous illustrations (so does the rest of the book; page through it and enjoy.) I’ll leave the book in the lab for you to peruse. Forsyth, A. 1990. Fruits of reason: interpreting the meaning of tropical fruit. Pages 52-59 in: Portraits of the rainforest. Camden House Publishing, Ontario, Canada. 26 Oct Competition I Ricklefs, R. E. 1997. Competition. Pages 341-360 in The economy of nature. W. H. Freeman, New York, New York, USA. 28 Oct Competition II Introduced species Simberloff, D. 1996. Impact of introduced species in the United States. Consequences 2(2) <http://www.gcrio.org/CONSEQUENCES /vol2no2/index.html> Accessed August 4, 2005. LAB Solving evolutionary puzzles in pollination biology Forsyth, A. and K. Miyata. 1985. Listen to the flowers. pages 65-75 in Tropical nature. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, New York, USA. WEEK 9 31 Oct “We can talk,” said the Tiger-lily, “when there’s anybody worth talking to.” —Lewis Carroll Through the Looking Glass Recommended More incredible illustrations in this chapter and in The essence of snake. Forsyth, A. 1990. Hermits and heliconias: The microcosm of plant and animal coevolution. Pages 74-83 in Portraits of the rainforest. Camden House Publishing, Ontario, Canada. 2 Nov Fundamentals of systems ecology: energy, nutrients, food webs, bioaccumulation. Carpenter. S. R. 1998. Ecosystem ecology. Pages 123-161 in S. I. Dodson, editor. Ecology. Oxford University Press, New York, New York, USA. 4 Nov Agroecology 1: Introduction to biogeography; agricultural communities and landscapes. DeVore, B. 2003. Creating habitat on farms: the land stewardship project and monitoring on agricultural land. Conservation in practice 4(2):29-36. Gliessman, S. R., E. Engles and R. Krieger. 1997. Interactions between agroecosystems and natural ecosystems. Pages 285-298 in Agroecology: ecological processes in sustainable agriculture. Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, Florida, USA Jackson, D. 2002. The farm as natural habitat. Pages 13-26 in D.L. Jackson and L.L. Jackson, editors. The farm as natural habitat: reconnecting food systems with ecosystems. Island press, Washington, USA. Quammen, D. 1996. Thirty-six Persian throw-rugs. Pages 11-13 in The song of the dodo: biogeography in an age of extinction. Scribner, New York, New York, USA. WEEK 10 7 Nov LAB Pleasant Valley Farm Field Trip Early departure for lab: Leave Dana parking lot at 9:40AM, return at 1:10. 9 Nov Exam II: Herbivory through pollination (1 November lab) 11 Nov Agroecology 2: The origins and evolution of agricultural practices Logsdon, G. 2000. Traditional farming. Pages 77-99 in Living at nature’s pace: farming and the American dream. Chelsea Green Publishing Company, White River Junction, Vermont, USA. Caufield, C. 1984. The harvest. Pages 123142 in In the rainforest. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois, USA. Diamond, J. 1999. To Farm or not to farm; How to make an almond. Pages 104-130 in Guns, germs and steel: the fates of human societies. W.W. Norton and Company, New York, New York, USA. WEEK 11 14 Nov LAB Seminar/discussion: Human population growth, consumption patterns, famine, environmental impacts. Avery, D. T. 2000. There is no upward population spiral, There is much less hunger than we’ve been told. Pages 48-64; 148-167 in Saving the planet with pesticides and plastic: the environmental triumph of high-yield farming. Hudson Institute, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA. Ehrlich, P. R. and A. H. Ehrlich. 1996. Fables about population and food. Pages 65-89 in The betrayal of science and reason. Island Press, Washington D. C., USA. Population Action International. 2000. How an early peak for population could improve prospects for biodiversity. Fact Sheet 12. Simon, J. 1999. Why are so many biologists alarmed? Pages 55-71 and 123-127 in Hoodwinking the nation. Transaction., New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA. 16 Nov Agroecology 3: Factory farming Small farms Sustainability Avery, D. T. 1998 Fall. The hidden dangers in organic food. Outlook. http://www.cgfi.org/materials/articles/2002 / jun_25_02.htm Avery, D. T. 2000. Is high-yield farming sustainable? Pages 213-237 in Saving the planet with pesticides and plastic: the environmental triumph of high-yield farming. Hudson Institute, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA. Beeman, R. S. and J. A. Pritchard. 2001. Ecological inspiration for agriculture. Pages 101-130 in A green and permanent land. Ecology and agriculture in the twentieth century. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, USA. Recommended Townsend, C. R, M. Begon and J. L. Harper. 2003. Sustainability. Pages 399-435 in Essentials of Ecology. Second Edition. Blackwell Publishing, Massachusetts, USA. 18 Nov Biodiversity and human harvest of food. Avery, D. T. 2000. Biotechnology: The ultimate conservation solution? Pages 357373 in Saving the planet with pesticides and plastic: The environmental triumph of high-yield farming. Hudson Institute, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA. Clark, C. 2004 September 3. This week’s news Chez Sophie Bistro. <http://www.chezsophie.com> Accessed September 3, 2004.This email contains Cheryl’s thoughts on caviar and conservation. Jackson, D. L. 2002. Food and biodiversity. Pages 247-260 in D.L. Jackson and L.L. Jackson, editors. The farm as natural habitat: reconnecting food systems with ecosystems. Island Press, Washington, USA. Larson, K. 2003. Extreme measures. OnEarth 25(3): 12-19. Vandermeer, J. & Perfecto, I. 1995. Biodiversity, agriculture and rainforests. Pages 127-147 in Breakfast of biodiversity: the truth about rain forest destruction. Institute for Food and Development Policy, Oakland, California, USA. WEEK 12 21 Nov LAB Food choice: Case studies, theory and experimental design Krebs, J. R., Davies, N. B. 1993. Economic decisions and the individual. Pages 48-76. in An introduction to behavioral ecology. Blackwell Scientific, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA. Raveret Richter M. R., Halstead J., & Savastano, K.* 2003. Seed selection by foraging birds. Pages 239-246. Exploring animal behavior in laboratory and field. Academic Press, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. . *Skidmore undergraduate Kierstin Savastano did the laboratory analysis of the caloric and nutritional content of these bird seeds as an analytical chemistry research project under the direction of Professor Halstead. Recommended These will add a human dimension to our theoretical considerations and field tests. Critser, G. 2003. Supersize me & World without boundaries. Pages 20-62. in Fatland: how Americans became the fattest people in the world. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. Nestle, M. 2002. Starting early: underage consumers; Conclusion: the politics of food choice. Pages 175-196 and 358-374 in Food politics: how the food industry influences nutrition and health. University of California Press, Berkeley, USA. Spurlock. M. 2005. Supersize me. DVD (Available in Scribner Library). 23-27 Nov WEEK 13 28 Nov THANKSGIVING BREAK LAB Food choice: avian field studies Field trip: Skidmore campus •Dress for the weather. Wear WARM clothing, thick socks, hats and gloves. •Meet at 10:10 in the lab, Dana 381. Forage! (Optimally?) 30 Nov Ecological consequences of genetically modified foods Pollan, M. 2001 Desire: control. Plant: the potato. Pages 183-238 in The botany of desire: a plant’s-eye view of the world. Random House, New York, New York, USA. Rauch, J. 2003. Will frankenfood save the planet? Atlantic Monthly, October: 103108 Richter, W. 2000. Lecture logic. Skidmore news, 13 October: 3. Recommended: Avery, D. T. 2000. Biotechnology: the ultimate conservation solution? Pages 357373 in Saving the planet with pesticides and plastic: the environmental triumph of highyield farming. Hudson Institute, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA. Schlosser, E. 2001. Why the fries taste good. Pages 111-131 in Fast food nation: the dark side of the all-American meal. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston, Massachusetts, USA. 2 Dec Ecology, natural selection, world cuisine and food choice. Billing, J. and P. Sherman. 1999. Darwinian gastronomy: why we use spices. Bioscience 49(6): 453-463. Kummer, C. 1999. Doing good by eating well. Atlantic Monthly 283(3): 102-106. Nabhan, G. P 2005. Discovering why some don’t like it hot: Is it a matter of taste? Pages 112-139 in Why some like it hot: food, genes and cultural diversity. Island Press, Washington, DC, USA. Recommended Nabhan, G. P 2005. Dealing with migration headaches: should we change places, diets or genes? Pages 140-162 in Why some like it hot: food, genes and cultural diversity. Island Press, Washington, DC, USA. WEEK 14 3 Dec (Saturday) Time to be arranged 6 Dec (Tuesday) 11:10-12:30 Gannett Auditorium LAB Chez Sophie Bistro Chef’s Choice Field Trip: What criteria do chefs use to select the ingredients they use in their cooking, and why? What are the impacts of these choices? Guest Lecture: Dr. David Carpenter, Institute for Health and the Environment, University at Albany, “Global assessment of contaminants in wild and farmed fish.” Kummer, C., S. Cushner, and E. Schlosser. 2002. The movement; Cheese Vermont. Pages 13-27 and 36-39 in The pleasures of slow food: celebrating authentic traditions, flavors and recipes. Chronicle Books, San Francisco, California, USA. Find information about the restaurant and chef at: www.chezsophie.com Hites, R. A., J. A. Foran. D. O. Carpenter, M. C. Hamilton, B. A. Knuth, and S. J. Schwager. 2004. Global assessment of organic contaminants in farmed salmon. Science 303: 226-229. Also, letters written in response to this article; Science 305: 475-478 9 Dec WEEK 15 12 Dec Student project presentations Presentations of food ecology research projects LAB Student project presentations Presentations of food ecology research projects; feast! A feast analyzed is worth eating. (apologies to Plato) 20 Dec FINAL EXAM 6:00-9:00 PM Dana 381 Additional references for fall 2007: Kingsolver, B., S.L. Hopp and C. Kingsolver. 2007. Animal, vegetable, miracle. HarperCollins Publishers, New York, New York, USA. Parsons, R. 2007. How to pick a peach: the search for flavor from farm to table. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. Pollan, M. 2006. The omnivore’s dilemma: a natural history of four meals. Penguin Press, New York, New York, USA. Vandermeer, J., and I. Perfecto. 2005. Breakfast of biodiversity: the political ecology of rain forest destruction. Second edition. Food First Books, Oakland, California, USA. Wansink, B. 2006. Mindless eating: why we eat more than we think. Bantam Dell, New York, New York, USA.