10.17.13 Transcription

advertisement

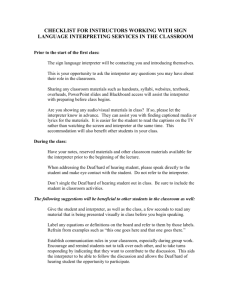

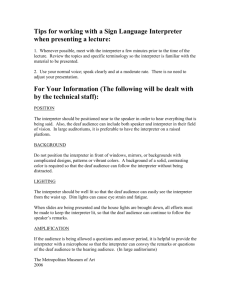

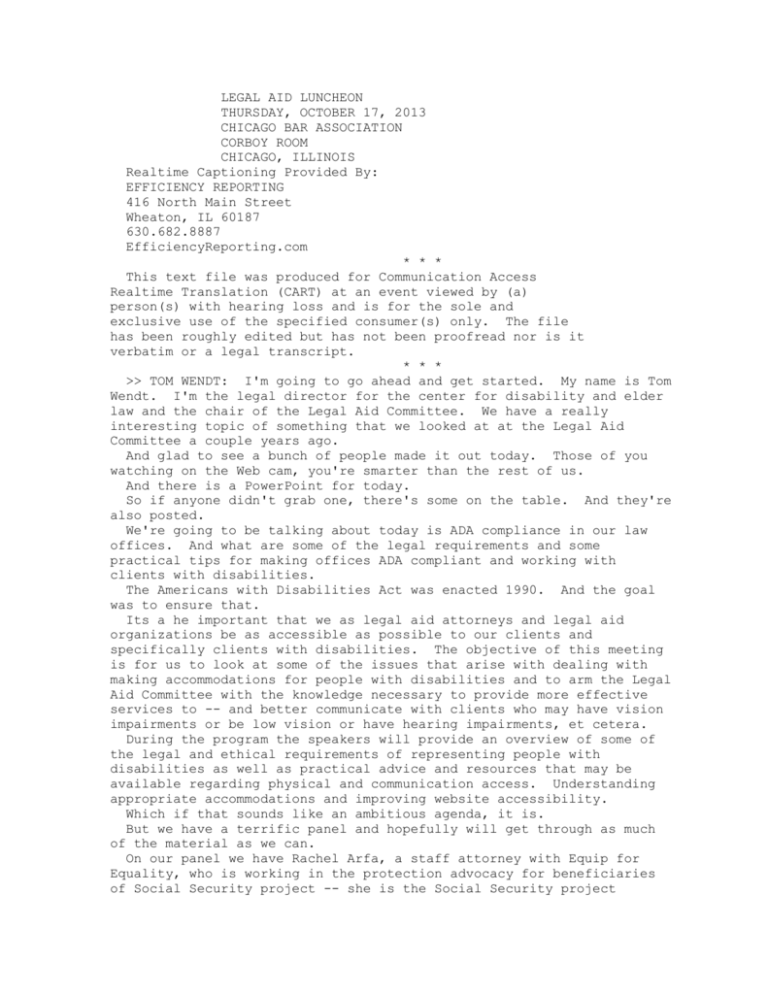

LEGAL AID LUNCHEON THURSDAY, OCTOBER 17, 2013 CHICAGO BAR ASSOCIATION CORBOY ROOM CHICAGO, ILLINOIS Realtime Captioning Provided By: EFFICIENCY REPORTING 416 North Main Street Wheaton, IL 60187 630.682.8887 EfficiencyReporting.com * * * This text file was produced for Communication Access Realtime Translation (CART) at an event viewed by (a) person(s) with hearing loss and is for the sole and exclusive use of the specified consumer(s) only. The file has been roughly edited but has not been proofread nor is it verbatim or a legal transcript. * * * >> TOM WENDT: I'm going to go ahead and get started. My name is Tom Wendt. I'm the legal director for the center for disability and elder law and the chair of the Legal Aid Committee. We have a really interesting topic of something that we looked at at the Legal Aid Committee a couple years ago. And glad to see a bunch of people made it out today. Those of you watching on the Web cam, you're smarter than the rest of us. And there is a PowerPoint for today. So if anyone didn't grab one, there's some on the table. And they're also posted. We're going to be talking about today is ADA compliance in our law offices. And what are some of the legal requirements and some practical tips for making offices ADA compliant and working with clients with disabilities. The Americans with Disabilities Act was enacted 1990. And the goal was to ensure that. Its a he important that we as legal aid attorneys and legal aid organizations be as accessible as possible to our clients and specifically clients with disabilities. The objective of this meeting is for us to look at some of the issues that arise with dealing with making accommodations for people with disabilities and to arm the Legal Aid Committee with the knowledge necessary to provide more effective services to -- and better communicate with clients who may have vision impairments or be low vision or have hearing impairments, et cetera. During the program the speakers will provide an overview of some of the legal and ethical requirements of representing people with disabilities as well as practical advice and resources that may be available regarding physical and communication access. Understanding appropriate accommodations and improving website accessibility. Which if that sounds like an ambitious agenda, it is. But we have a terrific panel and hopefully will get through as much of the material as we can. On our panel we have Rachel Arfa, a staff attorney with Equip for Equality, who is working in the protection advocacy for beneficiaries of Social Security project -- she is the Social Security project manager at Equip for Equality. Which is Illinois governor designated protection and legal advocacy organization for people with disabilities. Her work focuses on negotiating employment discrimination and civil rights cases. She has a profound hearing loss and wears bilateral cochlear implants. Our second speaker is Karen Aguilar, the executive director for the Midwest Center on Law & the Deaf. Karen has a master's in jurisprudence and health law from Loyola. As executive director of MCLD she trains attorneys, Judges and police officers about the rights of persons who are deaf and hard of hearing. And educates the deaf community about the rights under state and federal law. She has presented regionally, nationally and internationally and received numerous honors for her work. She has been signing since childhood, is a state licensed interpreter, and our third presenter is Kim Borowicz, a staff attorney at Access Living, she's been a staff attorney since 2008. Kim pursued a law degree with the hopes of becoming a disability rights advocate and presumably has achieved that. Her work focuses on representing people with disabilities in housing discrimination cases. I would like to introduce Rachel first as our first presenter. >> RACHEL: Thanks, Tom, for that introduction. Thank you to the CBA, and the legal community for having us here. My name is Rachel Arfa, I'm an attorney at Equip for Equality. I'm also profoundly deaf. And today we have over here the realtime captioning projected on the screen. And this is what I use to follow everybody else's presentation during the meeting. It's kind of -- on this side of the room, if you want to see the captioning you should feel free to move. The other thing is that because of my hearing loss, I talk with an accent. It's sometimes -- if I'm talking too loud, or I'm talking too fast, I need your help if you can tell me. If I'm -- need to speak up, please let me know. Or if you need me to repeat what I'm saying, I'm happy to do that. It doesn't hurt my feelings. So today we're going to talk about how we can make our organizations accessible to people with disabilities. What am I pressing? Sorry. >> That's okay. >> RACHEL: Okay. Today we're going to talk about what laws apply to people and organizations, to make them accessible to people with disabilities. The Americans with Disabilities Act was passed in 1990. And expanded in 2008, the definition of what makes somebody with a disability disabled. This was in response to federal courts decisions that -- the definition of disability, because now in 2008 ADA amendments Act, that definition is much broader. So the ADA prohibits discrimination on behalf of people with disabilities. Also in Illinois we have some laws that we have to apply, antidiscrimination laws that we should keep in mind when representing clients with disabilities. This includes the Illinois human rights Act. The Cook County human rights ordinance, the Chicago human rights ordinance and another rule that applies in the Illinois Supreme Court rules of professional conduct, where attorneys, they have some requirements that they have to follow as well. This is an overview of the Americans with Disabilities Act. There are five titles. Today we're going to focus on two of them. The first title prohibits discrimination in employment. Title II applies to state and federal -- local government entities. Those have to be accessible. Title III, which we're going to talk about, which applies to what we talk about today, is for places of public accommodation, have to be accessible. Title IV requires relay services which is a way that deaf and hard of hearing people can talk on the phone. Title V has a variety of sections regarding retaliation, protection. So today we're going to talk about Title II -- sorry, Title III. And the reason for that is that attorneys' services and offices are considered a place of public accommodation under Title III. One thing about Title II, if you're representing a client with a disability in court or in some kind of administrative hearing, the state and local government that you appear in front of, they reqire the administrative entity to provide accommodations for people with disabilities. And sometimes as atorneys we need to advocate to make sure the clients receive those accommodations. The Illinois general's disability rights bureau does a lot of work around the state to help it to be accessible. If you run into trouble there, that's a good resource. And so hee’s the law, Title III of the ADA. Provides that places of public accommodation, shall take steps to ensure that no individual with a disability is excluded or denied service, segregated or otherwise treated differently than other individuals because an absence of auxiliary services provided. As attorneys, we have obligations to make legal services accessible to people with disabilities under the ADA and under our ethics rules. As attorneys we have these ethical obligations but the rules of professional conduct like RPC 5.3, extends to our staff to make sure that staff treatment of people with disabilities is in line with ethics rules. The rules use the word "compatible" with the professional obligations of the lawyer. This rule goes on to define assistants and secretaries, investigators, law students and paraprofessionals. So how do we make sure you're accessible -- from the first moment that somebody calls your office or tries to come into the office, basically, you want to make sure that you are accessible, from the second they open the door and that there's no barrier. And sometimes you may not meet the person at the front, it might be an employee. You want to make sure you train your support staff on how to communicate with people with disabilities, how to explain obligations to be accessible under the ADA. And another issue that will allow people to make phone calls. Deaf and hard of hearing people use the video relay service. And in regards to using a TTY, a lot of people who are deaf and hard of hearing use a various relay services. And they call up, and hello, this is video relay operator 1234, I have a call from a deaf person. A lot of times you'll think you're getting calls from telemarketing or spam -- there's something unusual but it doesn't sound normal. Sometimes people – sometimes somebody is trying to access your legal services and sometimes the staff say we don't provide sign language interpreters. And then the staff person hangs up. So the person with the disability can't even access these services by telephone. So make sure that your staff know and understand how to do a relay call and how to communicate. There is a little bit of a time delay. But this is – main way a person with a hearing loss will have access and be able to have conversation with you. Some people do use a TTY, which means they might be typing back and forth with you, and are likely to be using a TTY, especially if they're calling from a prison, they may not have access to the Internet. Be patient with those calls. They're trying to access the important services that you have to offer. Another thing you want to do is think about the forms that you provide. Maybe your organization has sign-in sheets. Somewhere to sign in officially. Offer to help them with the form. Provide an alternative format. And Kim will talk more about that. Be sensitive with the visually impaired person to use a sign-in sheet. If they're not able to read on their own, provide some assistance. And another thing that comes up often is maybe your organization is not the right organization to provide services, maybe that isn't your area, you want to make sure that you refer to someone who is easy to find. Sometimes I have been looking for information for the self help desk and I look up the online listing which leads to the self-help desk listed in a library with no contact person listed. And I have spent an hour trying to figure out who the point of contact is. If it's hard for me to find out the point of contact, it's probably going to be hard for the person who's calling. So I try and make sure that they can find the right person by referring an easy-to-find source. This is important because they may need to ask for reasonable accommodation. Another issue is to evaluate your website on the issue of website access is divided among different court districts. The United States Department of Justice is evaluating the recommendation of website access. And we expect them to come up with new guidelines on what website accessibility looks like. But in the meantime you want to look at a website and make sure your videos are captioned or they have a transcript. If you use a podcast, make sure you have a transcript listed and you also want to have your other forms for the format which are downloadable. When representing a client with a disability, you want to ask what kind of accommodation the person needs. Ask the question, but don't assume that you know what kind of accommodation the person needs. This is -- a person with a disability has gone through a lot of trying to figure out what they need. Provide that accommodation. And just because you have met someone who is almost exactly like the person who has the same disability, don't assume that one thing that works with that person also works with the other person. Everybody has different needs that they go by. Here's one example of an attorney who did not provide appropriate accommodation. The individual complained against the attorney with the Department of Justice. It was a family law case. The person asked for the attorney to provide a language interpreter. The attorney did not understand. He used a relay service. And he expected the client to lip read. Here's what happened. The client didn't understand what the meaning -- and the attorney at times used the client's sister, who was not a qualified interpreter to interpret. So the DOJ investigation found that the attorney did not provide effective communication. The methods that were used to communicate -they had a sign language interpreter. And the attorney charged the client for this extra time. Which could have taken less time if the interpreter was provided. As a result, the attorney was ordered to pay a fine. And the attorneys fees were ordered waived. Be sure that you provide the accommodation and service. So as attorneys, we also have to think about our roles in advising. And to use a professional conduct to. To think about the economic, social, political factors that apply to the client's situation. These will include social background – Karen will talk more about this, but when you represent deaf and hard of hearing clients there's a wide range of activities related to hearing loss, because you might have someone who looks like they can talk and wear hearing aids or cochlear implants. I myself have bilateral cochlear implants. And compared to someone who doesn't speak and they communicate through American Sign Language, there's an identity and exposure results in a different distinct life experience and that influences attitudes about things. So you better be aware of these cultural differences. You're also going to have an idea what the person's main means of communication is -- if you're using sign language interpreter, you don't expect the interpreter just to be able to explain the terminology you use -- you need to make sure that you break down the language for the client and not rely on the interpreter to do so. Another issue comes up with confidentiality. We all know that you're not supposed to talk about our clients' case. But it's also coming up when you're talking about disability. Even for people who have hidden disability, they don't want anybody to know about their particular disability. Even if somebody does have a disability that's obvious, there may be parts of that disability that they don't want other people to know about. So you have to make sure that you will keep that confidential and check with them on what information can be disclosed. Another issue that comes up, sometimes that information from the client about the disability is shared with a family member who is not disabled. You want to make sure that you have the client with the disability's permission before you share information with their family members. Including anybody who's in the room. Finally, another issue that's come up is the issue of informed consent. I represent a client, she was asked to sign a form. And she had a visual impairment and she asked them to read the form. They said no. And she didn't know what was in the form, consent form. But that's not really informed consent -- she couldn't even access what the form was. So you want to make sure that the form is accessible. It is -- thinking of somebody who's not able to read or see the document, but also to someone who may not have the language to process what is in the document. Make sure that you break down the language and make it accessible. So then comes to the end, I'm going to turn this over to Karen now. And if you have any questions, here's my email. And phone number. You can give me a call. Thanks. >> KAREN: Thank you. Can everybody hear me okay? Yeah? Okay. My name is Karen Aguilar, I'm from the Midwest Center on Law & the Deaf. And I'm going to talk about some real life situations when a deaf person actually comes into your office and how you're going to communicate with the deaf person. First I'm going to quickly talk about some labels that are used for people with a hearing loss and you'll hear a lot of these. I'm going to talk about what's politically correct but I want you to take the lead of the person with the hearing loss, you can decide what to call the person. You'll hear the terms deaf, written with a capital D, a lower case d, heard of hearing, hearing impaired, hearing loss, deaf-blind. For the purpose of today I'm going to use the terms deaf and hard of hearing and mostly deaf. The term hearing impaired really isn't used that much anymore and can be considered offensive. So I'm not going to use that term for today. If a deaf person calls themself hearing impaired, go for it. Use it. But I'm going to for today use the word deaf, hard of hearing. How will deaf people communicate with you? These are the ways that I'm going to go over today and I will a he give you tips for these and some resources and ways to get the accommodations in your office for these different ways to communicate with deaf people. The first is through a sign language interpreter. We have an interpreter right here. Anytime during the next half hour or so you can look at the interpreter. She'll feel your eyes on her. Lip reading or speech reading, which is how Rachel sometimes communicates, through listening devices which are hearing aids or cochlear implants or a listening device with a microphone and hearing piece. Through CART or captioning which you see over here on the small screen to the right. Writing back and forth is sometimes used in a quick situation, and through the relay service, which if we have a couple of minutes, Rachel and I will show you at the end of the today. The definition of a qualified interpreter under the ADA is an interpreter who can receptively and expressively -- look at the deaf person, signs, understand them, and also voice them. Which means that they can also hear my words and sign them to the deaf person. It means that they're also unbiassed, it's not a family member. Do not ask a family member to come in and interpret for a deaf person you're working with. Also that they're effect at this and accurate. And especially in a legal system -- situation, that means they can accurately sign legal terms for you as well. We also have a state licensure law which means all interpreters working in the state have to be licensed. This is a quick site writing sample of a deaf person I communicated with. I'll quickly read it for you. This is a person who grew up using American Sign Language. Which means that written English is really their second language. I wait for processing ADA, one month too long. You know ADA. I think any person work job much maybe denied. Board afford service interpreter. What doing complain, waste time wait 2 months. Any question, ADA accept order? I will hear soon. I will be happy. Most of your clients are going to have American Sign Language as their first language and second language will be English. Most of your clients I'm going to generalize right now and stereotype -- are not going to be like Rachel. They're going to be low income, culturally deaf adults who have probably graduated from high school, some from college. But basically are educational -- our educational system has failed them, passed them from grade to grade and they probably graduated with, many of them a reading and writing level like this. So if they've asked you, for example, for a sign language interpreter, please give it to them. Writing back and forth is not going to be effective for them. All right? Tips for working with an interpreter. Let the deaf person decide where to sit. They'll sit probably where they can see the interpreter and the speaker. And possibly the PowerPoint, if it's a situation like this -- this actually this morning was a little hard to figure out for the interpreter, where can we sit where we can see the PowerPoint and the presenter and be in a situation where there's lighting, the presenters and so forth. A large group, only one person can speak at a time. It's impossible for an interpreter to sign for two people speaking at the same time. When I'm talking to the deaf person, I shouldn't be looking at the interpreter and talking. I should maintain eye contact with the deaf person. It's actually quite rude to be looking at the interpreter or somebody else. It's respectful to look directly at the deaf person. Once the meeting begins, continue at a normal pace. If the interpreter is behind, the interpreter will let you know. If you need to repeat something or if you need to slow down. Everything will be interpreted. And should be interpreted. That's the interpreter's job. So if I'm in a meeting with a deaf person and the interpreter is there and the phone rings, maybe the meeting is taking longer than expected, or if you're frustrated with the situation like with any client and my phone rings and I'm on the phone and God, this is taking for ever, or I have to pay for this interpreter because God, it's an extra $100 for this interpreter to be here. The interpreter is interpreting everything I'm saying. Be very careful. All right? And by the way, CART did everything as well. If the client has low language skills like you just saw might be important to have a second interpreter there, a CDI, certified deaf interpreter. Maybe someone moved here from another country, learned only home signing growing up, regular sign language interpreter is not good enough. One sign language interpreter signing regular American Sign Language signs and a second deaf interpreter here taking the regular signs and dropping it down even more. To lower language skills. For that deaf person to understand. Now, if I'm here and the interpreter is here and I'm curious about how she learned line language, I wouldn't walk up to her and say how did you learn sign lake? I'm talking to you. Can you tell me how you -- and this has happened to me before. No, I'm actually talking to you. How did you learn sign language? Can you tell she keeps signing and she's not answering me? That's exactly what she's supposed to be doing. So don't have a conversation with the sign language interpreter. Once the job is totally over and everybody has left, if the interpreter is still around, you can ask her. But not during a job to have a conversation with her. Don't coach the interpreter. Had is also happened to me. One time we were about to start a meeting, and the hearing person said to me, you can start signing now. It's like, thank you for letting me know. I know that. And also one time this person said in a different situation, the person said to me, you mow, if you use more signs, he would understand you better. And this person who knows sign language. I thought thank you very much. That's wonderful advice. I think it's important to have one person in your office have the relationship with the interpreter agency or now how to schedule a sign language interpreter for you. This helps with billing especially so you don't have two people calling and scheduling interpreters from two different agencies. It's important to have that one person scheduling an interpreter because that person is going to know the job that you're scheduling the interpreter for. They know if you need to ask for a legal interpreter, they know for example if that deaf person who's coming in has a language skills, if they need to request a CDI in that situation or not. They know if you've actually requested an interpreter from two different agencies, if one agency sends an interpreter, they know to cancel the request from the second agency. So I think it's really a good idea to schedule -- I am a he sorry, to designate one person from your office to do all the requests for sign language interpreters. This is a list of the large interpreter agencies in the city. If you decide not to use an agency, at the bottom is the list -- is the website linked to the Illinois deaf and hard of hearing commission. They have a list of all the licensed interpreters in the state. If you want to call or email all the interpreters on your own in your area, you can do that as well and avoid going through agencies. That's up to you. A deaf or hard of hearing person might come to you and not know sign language or they might prefer to lip read you or speech read you which basically is you sitting across from them with good lighting and they're lip reading you. Remember they're not going to understand every word. Some of it is going to be guessing. So you might have to repeat yourself. Be patient. Make sure that you're facing the person sitting right across from them. Maintain eye contact, again, make sure there's good lighting. Speak clearly. Don't overexaggerate your mouth, you'll look silly anyway if you do that. Give them as many visual cues as you can but don't try to flap your arms around, that will also look silly. If you say something the first time and they don't understand you, don't keep resaying the same thing over and over again. If they didn't understand the first time, it's probably hard to see on the lips, so change it and say it a different way. I would suggest also after you get to three or four sentences in, make sure they understand you. Say, do you understand? Do you have any questions? Does this make sense? Say B and P everybody for a second. B, P, looks the same on the mouth. Right? So just know that some words, again, are going to be guessed by the deaf person. Don't cover your mouth, don't have food in your mouth, don't chew gum at the same time as talking, it's hard to lip read someone with all this stuff in your mouth. If you have a mustache, you might have to comb it to the side, one time a man had a handlebar mustache. And we showed up -- Rachel said I don't need an interpreter, I will go with you if you have any questions. I signed something, and this man had a huge mustache. And we went oh, gosh. (Laughter) >> KAREN: Don't say never mind. Or it's not important. If you say something to a deaf person they don't get it over and over again, say, huh, never mind. No, it was important. If you said it the first time, it was important enough to say it. Worse come to worse, pull out a piece of paper and write it down. And be patient. Okay? Sometimes the deaf person is going to come to you wearing hearing eights or cochlear implant that might increase sound enough they will get some cues from that technology. Here are some websites that give you information about some of these listening devices if you want to read more about it or if your office wants to buy any type of listening device. Court houses sometimes use these as well. Your client might show up at a courthouse and request a listening device to be used. They might clip a microphone on to your clothes. Don't refuse to do that. I have seen people refuse to that that before. No big deal, clip it on your clothes and wear it. You might want to help a client by asking a Judge to put it on when he's speaking. Convince the judge to do it. CART, here's some websites as well. Your client might request cart when you go to Court. Help advocate for your client when you do that. It's not easy for her, but she's trained. Pretty easy, you set it up, look at a screen and it gives your client communication access. Writing back and forth; this is for a deaf person who might prefer to use this as a way to communicate with you. I would not suggest using this for an hour long meeting. This is just a short-term, quick conversation or at a help desk. Keep the phrases short and simple. Again, let the person keep the piece of paper. So many times the person comes to me and said they wouldn't let me keep the piece of paper. If you need to make a copy for your records, do that but let the person take the piece of paper with them. Relay. Rachel mentioned this as well. Please train all of your staff who answer the phones in the front what a relay call is. I think we'll have a couple of minutes to do a practice relay call so you can hear what it sounds like. It's not somebody trying to sell something, a telemarketer. They say the person is calling through the relay service. Hello, relay. Relay. Don't hang up on them. Okay? You don't need a TTY in your office. That's a -- does everybody know what a TTY is? A little square keyboard with couplers on the top that you put your phone on. They're pretty much outdated now and not a lot of people use them. That's what's in the prisons now. There aren't video relay in the prisons. They will probably call you with TTYs. You might have one dusty in your office still. But you don't need a TTY in your office or a video phone in your office to accept a relay call. Just a regular standard phone. When a deaf person calls you and said call me through this phone number, you can call through that number and you will automatically be connected through relay to that deaf person. Don't say relay, tell them that I, blah-blah-blah. You are just talking right to that deaf person through this relay service. Relay is -- if I'm going to call Rachel, I pick up my phone and I'm talking through an operator to Rachel. So this relay operator is signing my words and they're looking at Rachel, signing to her through a video screen. She's signing to this operator who knows sign language and voicing her sign toss me. It's an in-between operator who knows sign language. For a TTY, it's the same thing. A deaf person is typing, the operator is voicing the typed words to me and vice versa. There have been -- there's just recent time I was on a conference call with Rachel and the relay operator, the interpreter and the very flat tone was making a lot of mistakes. I said can you please swap out to a different interpreter. I knew they weren't understanding what was going on. And it didn't sound like Rachel. If you're in the middle of a car and it doesn't feel right to you, ask to swap out interpreters. If you think that the relay operator is -- maybe they don't know legal terms, and you know that this deaf client of yours needs to understand what you're saying and it just doesn't feel right, ask to swap out an interpreter to an interpreter who knows legal terms. Don't take a chance if it doesn't feel right to you that the call isn't going right. Swap out interpreters. The bottom website is website if you're interested in learning more. There are relay operators who are trilingual, Spanish, English, if you have clients who are Spanish speaking, use this website as a resource. General tips when working with deaf clients. When they ask for an accommodation, for example, if they ask for an interpreter, believe them. Don't say let's try writing back and forth the first time. Don't say let's try lip reading the first time. If they ask for an interpreter, believe them that they need it. Put some money aside in your budget for accommodations. If you use it that year, great. If you don't use it, you have the money there for the next year. I would suggest scripting. Wright up a script for your front office staff. When I train police officers and hospitals and everybody about talking and working with deaf people, usually they're just nervous. They don't know what to say when a call comes in and a deaf person shows up. You might want to think writing some sentences down that the staff can use when a deaf person shows up. Don't talk to family members. They're not your client. So frequently a deaf person will talk to me and say, you know, the attorney wants to talk to my mother. And this is a 30 or 40-year-old. I say why do they want to talk to your mother? They're not the client. Make sure to talk only to your clients, not the family members. Unless you have permission of course. When you confirm an appointment with a client or when they ask for an interpreter, I would take a second and make sure an interpreter is actually coming. Worth the quick phone call to make sure you have an interpreter coming for an appointment. Many times when I refer deaf clients to your agencies, you refer them back to me. Just because I'm a deaf agency. But I've actually referred them to you. Tell your front office staff not to refer everybody to me. Because we're a referral agency. We don't actually represent clients. So thank you for the referrals, but they're for you. (Laughter) >> KAREN: If you're -- a deaf person shows up at your office -sometimes it's hard to take the time out of phone calls and what's going on. But it would be great if you could find somebody who has a minute to talk to them. I'm sure you don't have interpreters on staff. So gab a piece of paper and figuring out their problems would be great. If you don't have time, you know, sometimes relay calls take an extra minute. I know it's hard. The front office staff putting someone on hold. All -- you know, is hard. So if you can find somebody to take a minute to take those calls would be great. And maybe having somebody as an expert in your office in disabilities would be great also. Quick -- do I have a quick second? This is quick. You can read through it later about what we do. We have an attorney referral service, don't have attorneys on staff much we do a lot of education in the deaf community about their rights. Under state and federal laws. We do workshops. Our website has 60 legal terms in ASL. We do a lot of he had education of the deaf. These are great articles. This my goodness, the last thing I'll say. A deaf man went to his regular doctor and -- who he's gone to for many years much on the side said I was culled for jury duty. And his doctor pulled out his prescription pad and wrote above mentioned person has jury duty, this person is deaf and dumb, uses only sign language, has no communication skills. Kindly excuse him from jury duty. This was in July. So please, just because a person uses American Sign Language does not mean that they're dumb, does not mean that they have no communication skills. So hopefully you will -- just because somebody is a little different than you, please respect your client as people. That's the end of my presentation. If you have any questions, let me know yeah? >> I was wondering is there a cost for that relay service? And you also call your clients and they call you ->> KAREN: There's no cost for the relay service and -- what was the second question? >> You said that the client could give a phone number to call. But what if you want to call your client and they aren't around. They call the relay service? >> KAREN: You call the phone number they give you and leave a message. Yep. This one right here. To the right. There you go. You just did it too far. You go to the left of it. There's the triangle. >> KIM: On line? >> RYANN: I can do it too. If you want to tell me when to change. >> KAREN: Which is your first one? >> KIM: A title slide. There it is. I can do it from here. >> RYANN: I can do it from here too. >> KIM: I will be speaking about how to accommodate clients who might be working with you, maybe vision impaired or have blindness. My first slide talks about a lot of the different types of paperwork we use as lawyers. I always joke that lawyers really like paper. And we do. The written word is a really important part of our work. But the written word can also pose incredibly huge accessibility issues for folks who are low vision or who have blindness. Think of paper as steps would be to someone who uses a wheelchair. Paper is that way for folks who are low vision or blind. So kind of take an inventory of all the different paper you use in your office, and -- I've done a list here of different types of paper you might use. And try to make sure that every piece of paper you have is available in what's called a plain text format. Plain text is just a way of saying a Microsoft Word document that just has the text in it. This is important because Microsoft Word documents can easily be changed, you can usually change the font size. The font color. The font style. Also when you have a Microsoft plain text document, it can easily be changed into braille. Can easily be printed on a braille printer. There's certain things that depend on the person. So I don't think that there's a rule on what is large print. And this kind of goes with the reasonable accommodation framework. So here when we're talking about providing paperwork and in an access many format, we're talking about reasonable accommodations under the ADA. Reasonable accommodations is an individualized inquiry. So it's whatever the individual needs as an accommodation. So I've heard all kinds of things about rules about large print. This is a place where you should really ask the person who has low vision what works best for them. There are also different grades of braille which means different levels of braille. So if someone's using braille you would also want to ask that. Don't assume just because someone is blind that they would need documents in braille. I've made this mistake before. And you'll go through the trouble of printing something in braille, and the person can't read braille. And maybe it's because they've recently lost their vision. Or maybe it's because they just never learned it. But don't go through the trouble of providing an accommodation that maybe someone doesn't even really need. Ask the person what they need. Some people might want to document -- a document read to them. I see this a lot with older adults who maybe lost their vision due to aging, the aging process. Younger folks like me, I have vision impairment, I do not want someone to read something to me. Really makes me angry. When I'm prepping with a of -- presenting with a document and I'm told it's not available in another format, and the person offers to read it to me, I'm able to read the document, as long as it's provided to me in accessible format. Another thing I didn't put on here is way finding. So another big barrier for folks who are low vision or blind is finding their way. Finding their way to your office, finding their way around the courts. So just really thinking about that. Like if you have a court hearing with a client, you know, maybe offer to meet them at the nearest L station. Maybe you're taking that same L too, helping them walk to where you're going to court. It's very hard when you're vision impaired or blind to read street signs and see a room number and all those kinds of things. So lending a hand in that way can also help. A little bit of thinking ahead on those kinds of things. Something that I do is sometimes you won't know if someone needs to be guided. So I'll just ask someone, do you need an arm? If I'm walking with someone who is low vision or blind, do you need an arm? And usually they'll just grab my elbow. And they'll walk along next to me. They can get a lot -- someone can get a lot of information just from your elbow as you're walking along. This has already been said. I want to designate someone in your office to provide accommodations. This could be the same person in your office who is designated to provide accommodations to employees. So can possibly even be someone in the human resources department. And I want to reiterate that don't send clients with disabilities to Access Living just because they have a disability. I see this a lot. Where someone has already called other legal aid places and for whatever reason they are referred to Access Living because other main focus is disability rights. Really work at your different legal aid organizations to provide accommodations to folks who have disabilities. I have a couple slides about fillable forms. This is a form that's on the video Chicago website to look up a ward. An online fillable form or you can type into the form. These types of forms are very accessible for people with vision impairments. Another form I really like comes from Illinois legal aid on line and it's a fillable online form to help someone do a Power of Attorney. There's certain types of adaptive software. Do we have time to show? >> RYANNE: Yeah. >> KIM: We have different types of adaptive software that folks who are low vision can use on their computers. Go ahead. Yeah. (Music) >> Sorry, guys. >> KIM: That's okay. There's always tech issues. There -- neither are captioned. No. >> This is the home page of the handbook for educators and museums on the art beyond site website. Listen to how a blind person with a jaws screen reader will experience some of this page. >> Graphic program in -- graphic photo of a teacher and student. Graphics attached step by step through the entire process. This page with graphic accessibility rules written. This page with graphic photo of hands exploring the tactile drawing of Pablo Picasso's -- facilities accessibility. Graphic for educators and museums. This page with graphic disability awareness. This page with graphic photo of signing AVS. Disability and inclusion. This page with graphic human resources, this page with graphic photo of hands on the computer. Graphic employed with a museums and the arts. Handbook takings you through the process of creating accessible programs for people with visual impairments. Graphic photo of a man reading grail descriptions of a display of a printing company by a young woman at the museum of modern art, New York. >> KIM: That's an example of a piece of software called jaws, it's an acronym, JAWS. Job access work software, I think is what it stands for. But as you saw and heard, it can read through a website. So it's a good point to note that a website has to be made accessible for this type of screen reader software to work. And I provided other slides, some resources where you can check your legal aid organizations' website to make sure it would work with that type of software. This next video will show another piece of software. (Video) >> Were you ready? >> KIM: Oh, yeah. Sorry. (Video) >> INTERPRETER: Can you click on the closed captioning and maybe it will pop up? There is a button for closed captioning. On the right. (Video ) >> Screen application for the visually impaired. It allows you to see and hear everything on the computer screen, providing access for different applications, for processing email and Internet. Some of the enhancement fee furs are the power, the power can magnify the screen up 36 X. There's different types of screen that can be utilized as well. Right now we're looking at the full -- you can see the entire screen. Is at full magnification. We can do a lens view, it's like a hand-held magnifier, where you can pass it over. Where you need that enhanced feature. You can look at the live view if you're doing any detail reading and hit just that particular area. The line view. And we're going to go back to the full. And we're going to look at some of the other enhancement features. The next will be the color. Where you can change the colors. You can invert the brightness. We can also create a yellow and black scheme. We can all -- also do black and white invert. That's the yell low is harsh on your eyes or maybe you do need that particular contrast. We can also enhance the pointer or you can find the mouse pointer on the screen with a full cross hairs. We can also enlarge it and change to different colors as well if you need that particular enhancement. >> KIM: If your client has access to this type of software, a lot of times if you have documents to send in, you send in plain text, Microsoft Word documents. They're able to manipulate those documents in ways using their software to enlarge them. I have a vision impairment and I have that second piece of software on my computer. So as long as people are just emailing me documents, I'm able to enlarge them without the person -- the person e-mailed back to me, doesn't necessarily have to change the font size or anything. Okay. I just -- I wanted to make a point about contrast on websites. These are three examples of bad contrast. The first comes from an email chain. The email had a background color. And as you start to reply to the emails, the coloration, it becomes really hard to read. Of course the best contrast is always black and white. But of course like websites, you might want them to be a little bit more colorful than that. The middle -- the middle example is actually a website about making websites have better contrast. And actual website isn't in very good contrast. The bottom is from the national federation of the blind. And I feel like the right hand part of that bottom website is not -- does not provide very good contrast. Contrast of the words, the text on the background can really make a difference in the accessibility for folks. Also you saw with the screen reader software that putting these tags on graphics can really help folks who are blind know what a graphic is. Know what the picture is of. I provided a lot of resources because screen reader accessibility can get super technical. If you're not computer savvy, as I am not, these are some really good resources. I've also provided a resource on making adobe acrobat PDFs accessible. If your PDF is just an image, you're not able to scroll over the text with your cursor and make the text highlight, like you wouldn't be able to copy and paste into a Word document, then the screen reader is not going to be able to read it. That's a general simplified rule. There's a website I provided to provide more information. I provided a list of organizations in Chicago that work with folks who are low vision or blind. And I know this presentation was quick, so I'm always happy to help with any type of kind of input on disability accommodations. I know that my presentation focused on vision impairment, and that is my own disability, so it's kind of the one that I'm most familiar with. But in my job I am constantly working to accommodate clients with disabilities. And I know that some of this might not resonate until you have a client who comes to your door who has a disability. So if that moment arises, always feel free to contact me. >> TOM WENDT: First, before we get into question, I would like everyone to give Rachel and Karen and Kim a round of applause. Because that was terrific. (Applause) >> TOM WENDT: I do want to open it up to questions. If anybody has any. >> Do we have time for them to do the relay? Demonstration? >> TOM WENDT: Depending on how many questions. Yeah. Why don't we do that first and take questions after that. Okay? >> RACHEL: I have on my phone the captions relay service. So I can call -- someone wants to call -- >> Want to call me? >> DINA: At a break? >> What's your number? (Number provided) >> RACHEL: I'm calling now. And now in sign language interpreter ->> KAREN: If anybody wants to come up and see. The interpreter just appeared. Her screen is split, so on the bottom Rachel can see herself. On the top the interpreter is signing one minute. >> DINA: Hello? Hello? >> Hello. Hi there. Someone who is speaking in sign language is calls through the relay service. Hi there. I'm Rachel and I'm calling to speak with Diana. >> DINA: Hi, Rachel. This is Dina. >> Hi there. Thank you for coming to the event today. To the presentation today. I appreciate it. >> DINA: Sure. Is there anything I can help you with today? >> RACHEL: I think everything is good. Thank you. >> DINA: Okay. Bye-bye. >> KAREN: Go longer. >> DINA: Go longer. Sorry. >> DINA: We're not signing off yet. So Rachel, tell me -- tell me what you're seeing on your phone. >> RACHEL: Right now I am seeing a split screen. So I'm going to show you what -- I'm signing myself. And so I have a sign language interpreter and she's interpreting everything that I say. And so... the picture. >> DINA: So Rachel, if you don't have a cell phone and you're making a relay call from your home, do you have to have a computer set up near your phone so you can see the interpreter? >> RACHEL: Yes. I can do two different things. I can use my iPad with my Web cam. And then also I can use my laptop. When my computer is working. And with that I have a Web cam. So that will help me to -- so it's all through the Web cam. I can use the Web cam. Also I can use -- I can talk to another deaf person. So it's about -- me speaking to another deaf person. >> DINA: Do most deaf people, like low income deaf people who might not have computers or other equipment, how would they access the relay? >> RACHEL: Well, first if -- sign language would be through the relay. They would probably use the TTY. For low income, maybe they -they have a computer. But if there's no Internet, you can't use it. You need to have Internet service in order to use the video phone. Or video relay service. So one of those people would actually use the TTY and use the other relay where they would type back and forth. >> DINA: Okay. >> RACHEL: And know in rural areas they don't have strong Internet connections or strong Internet service, so it will be hard to use. In a video phone too. >> KAREN: Can I also add something to that? Access Living has a video phone in our lobby that's available to clients as well. >> DINA: Hold on. Just one moment, please. Kim is actually speaking. The other presenter. She's not on the phone with me. >> KIM: I'm sorry. >> DINA: So should we end the call now and then Tim can ask for questions? So we free up the operator? >> RACHEL: Okay. Thank you. >> DINA: Thank you. Bye Rachel. >> RACHEL: Bye-bye. >> I have a question. I do have a question. My understanding about video relay is that it's possible to be in the same room. Do you have to be in the same room or different rooms in order to make the video relay work? >> RACHEL: Yes. The video service, you should not be -- they're usually pretty -it's not a tool that you would use with a meeting with somebody. So you would want to use a sign language interpreter. >> INTERPRETER: I wasn't understanding, sorry. >> RACHEL: The MCC has rules about people not being in the same room to use the video service. The type of case that you're referring to. And so in that -- so this is not something you would use to meet with a client in person. You would either use a video remote interpreter where you can call an interpreter to come in -- that's something else we can show you, or you want to hire a sign language interpreter for your meeting. But this is a way to demonstrate how you can make a phone call so that people understand how the video relay service works. >> KAREN: This is not a substitution for meeting with clients. And not hiring a sign language interpreter. >> KIM: I have a case like that right now where the defendant keeps calling the person, like through the relay. And I made a reasonable accommodation request, the client would like you to provide him with a sign language interpreter. And the defendant responded I have been providing them sign language interpreter. I've been talking with them through relay. So I'm trying to make this point with this defendant that the interpreting through the relay is not a substitute for face to face meetings with sign language interpreters. In meeting with you. Especially when you're talking about legal concepts, especially when you're having really important meetings with your clients. The phone really is not a substitute for a face-to-face sign language interpreter. >> RACHEL: I also have a screen shot of the phone call that -- in case you missed it. If you wanted to see what it looked like. I'm happy to show you. >> Ryanne: Kim, what were you saying about Access Living? >> KIM: I interrupted the call. If I think of something, if I don't say it right then, I'll forget. Access Living has a video phone -- I think one or two available in our lobby for folks. They can can use it for 30 minutes at a time. So I have actually had some clients where they come back to Access Living to use the video phone and I get a call from Access Living. Like on my caller I.D., Access Living is calling you. It's actually one of my clients who's down stairs in the lobby and wanted to just quickly maybe set up a meeting with me. >> TOM WENDT: Are there any other questions? Yeah? >> Services -- 24 hours? >> KIM: Yeah. >> Okay. >> TOM WENDT: I actually had one question too. We were talking at the beginning of the presentation a little bit about some of the rules of ethics, particularly rule 1.6 regarding confidentiality. Our interpreters govern under confidentiality the same as any other nonattorney in the office would be? >> KAREN: Is I would say yes and no. That's my easy answer. The licensure -- the confidentiality extends with -- but unfortunately our licensure law does not include confidentiality. So there's under the code of ethics for interpreters, it says yes they're supposed to keep everything confidential. But if they're called to testify, the difference tore story. So that's my yes and no for you. But interpreters quickly forget everything they do once they leave the room. (Laughter) >> TOM WENDT: Any other final questions? Okay. Well, I would again like to thank our presenters today. And are there any announcements or any other business? None? Last time we ran short so we didn't do announcements and now we don't have any announcements at all? >> Ryanne: I think Alel. >> A quick announcement for everyone. If you have not talked to the CBF yet, about your opportunities that you have on the ALAO, we did launch the volunteer search, the new search, the new system. So please get in contact with her because we're going to start promoting it during pro bono week come Monday. Make sure you you get in contact with them or us if you are outside of Cook County. So we also have flyers over here if you want to check them out. Thank you. >> TOM WENDT: Great. Yeah? >> The law project is having our fund raiser tonight. It's called link by link. We're going to be honoring the pro bono coordinators as well as several clients and volunteer attorneys that we work would. >> TOM WENDT: Where's that at? >> Skadden, 155 north Wacker. 5:30 to 7:30. >> TOM WENDT: Perfect. Any ->> KAREN: Midwest Center on Law and the Deaf has a new young professionals board. If you're interested in joining, everything's on our website. And our Facebook page. Midwest Center on Law & the Deaf. >> TOM WENDT: Any other announcements? We don't have a legislative update today but I am assure we will next time. Our next meeting is on November 14th at 12:15. And if there's any other comments or -- I'd like to get -- again, thank for the third time now our presenters. If you would give them a hand again. (Applause) >> TOM WENDT: And I will -- we will see everybody and talk to everybody on the 14th. Thank you. -END* * * This text file was produced for Communication Access Realtime Translation (CART) at an event viewed by (a) person(s) with hearing loss and is for the sole and exclusive use of the specified consumer(s) only. The file has been roughly edited but has not been proofread nor is it verbatim or a legal transcript. * * *