short paper

advertisement

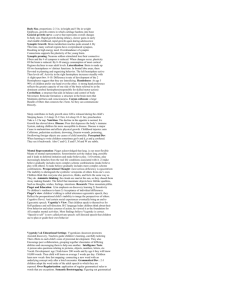

Local validation study of the Italian version of the Aggression Questionnaire (AQ) in Southern Italy M. Sommantico*, M. Osorio Guzmàn**, S. Parrello*, B. De Rosa*, A.R. Donizzetti* * Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II”, Dipartimento di Scienze Relazionali “G. Iacono” **Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala The Buss and Perry AQ (1992) remains even today one of the most widely used instruments in the evaluation of different levels of aggressivity in young adult and adolescent populations. The original version was validated across a sample of 1253 subjects and composed of 29 items (some taken from the exploratory factor analysis of 52 items that comprised the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (BDHI, 1957) with other new items added). This version was organized according to four factors: the first two, physical aggression (9 items) and verbal aggression (5 items) represent the functional or motor component of aggressive behavior; rage (7 items), the affective component of aggressive behavior, includes physiological arousal as well as the preparation for aggressive action; hostility (8 items) then represents the cognitive component of aggressive behavior. A strong correlation between physical aggression and verbal aggression emerges in the AQ validation study (Buss, Perry, 1992) as well as a moderate correlation with hostility; rage is significantly correlated with the remaining three factors. As noted, this version is quite reliable in evaluating the components of aggression. In terms of the AQ validation in other countries, many studies have been conducted in Europe, the Americas and Japan. In Europe, in addition to Italy, similar studies have been run in Spain (Garcia-Léon et al., 2002; Rodriguez, Peña, Graña, 2002; Gallardo-Pujol et al., 2006; Santisteban, Alvarado, Recio, 2007), Holland (Meesters et al., 1996) and Germany (von Collani, Werner, 2005). Among the studies in Spain, the results of the first three (Garcia-Léon et al., 2002; Rodriguez, Peña, Graña, 2002), support the four-factor structure of the AQ in terms of the internal coherence and the temporal stability of the single sub-scales in their reliability analysis, components and convergent validity. The final study on the other hand, aligns itself with other studies (Bryant, Smith, 2001; Morales-Vives,Codorniu-Raga, VigilColet, 2005; Vigil-Colet et al., 2005; Ang, 2007) in which the benefit of using a reduced version of the AQ allows for quicker implementation and still maintains high levels of validity and reliability (Gallardo-Pujol et al., 2006). The Dutch study highlights the existence of a rare fit to the four-factor model, in the study sample, incremented by the elimination of one item from verbal aggression and 2 items from hostility. The study further underscores the need to evaluate the components of aggression as a whole but also as individual phenomena (Meesters et al., 1996). The German study, which also verified the four-factor structure, provided satisfactory results evaluating the psychometric qualities of the sub-scales and the instrument as a whole. The internal consistency and temporal stability of the scores obtained reached statistical significance, as did the concurrent and discriminate validity of the components. The authors highlight that the four components of aggressive behavior can manifest themselves in basic personality traits including fight or flight response, irritation or availability (von Collani, Werner, 2005). Even the two studies conducted in Japan (Ando, 1999; Nakano, 2001) support the four-factor model of the AQ reporting results statistically proportionate for the internal consistency of the four sub-scales, and isolating a promising instrument in the questionnaire for measuring aggression. In particular, the Nakano study (2001) underscores how the Japanese version of the AQ would be strengthened by the removal of the two items with inverted scores. Lastly, in the American studies, the results of the only Canadian study based on the French version of the AQ (Bouchard, 2007) support the four-factor structure, as well as the internal coherence, the inter-scale correlation, the criterion, concurrent and discriminate validity, and the reliability in the use of student and other populations. In the study run in El Salvador where the Spanish version was used, the authors propose the elimination of two items, corresponding with acceptable psychometric indexes (Sierra, y Gutiérrez, 2007). Since the majority of studies cited in the literature have used non-clinical subjects from student populations, it is important to cite a recent study conducted with a more heterogeneous sample, with the purpose of evaluating the ability of the AQ to be generalized. (N = 1200 representative adults from Hungary) (Gerevich, Bácskai, Czobor, 2007). Although is has been shown that a more fair four-factor model results from restricting sample subjects by age (as compared to samples used by Buss and Perry (1992) and in the majority of the studies cited), the same structure is statistically proportionate even with a more comprehensive sample. The data from the study therefore confirm a benefit in using the AQ on the general population and not only on adolescent and young-adult populations. In short, the results of studies that focused on the analysis of the psychometric properties of the AQ on specific clinical populations (psychiatric patients or aggressors), seem more contradictory in terms of being a good fit for the four-factor model or with respect to the internal consistency values of the individual sub-scales (Williams et al., 1996; Morren, Meesters, 2002; Fossati et al., 2003). The Italian version of the questionnaire was created on the basis of a native speaker’s translation, compared with the original and deemed sufficient. Up to now the psychometric properties of that questionnaire have been tested on three groups: a clinical sample (N = 461, average age = 33.9), a first non-clinical sample (N = 563 adolescents between the ages of 13 and 19), and a second non-clinical sample (N = 1029 young adults between the ages of 20 and 35). All groups were taken from Northern (clinical sample) or Central (non-clinical samples) Italian populations. The internal consistency values (Cronbach alpha values) were satisfactory across all groups on both the entire questionnaire as well as on the individual sub-scales (with the partial exception of verbal aggression). In terms of the components validity, the factor analysis results show that the solution in non-clinical samples is stable, sufficiently clear and definitive, replicating the solution indicated by Buss and Perry (1992). Essentially, the data from the validation study of the Italian AQ (Fossati et al., 2003) confirm that the instrument is statistically valid in measuring aggression, presenting sufficiently reliable internal consistency and a sufficient components validity in the sample taken into consideration (Fossati et al., 2003; Maffei, 2008). On the other hand, the adolescent and young adult population in Southern Italy presents different socio-economic characteristics (Parrello et al., 2008; SVIMEZ, 2008) than the other Italian contexts (Central and Northern). On the basis of the discussion above, the objective of the present study is to analyze the psychometric properties of the Italian version of the AQ across a representative sample of Southern Italian adolescents and young adults to verify by confirmatory factor analysis the questionnaire structure, compared in many studies. Methodology Participants 860 subjects participated in the study, 41% male (353 subjects) and 59% female (507 subjects). The average age was 20.10 years (s.d. = 3.70) with a range of ages from 16 to 57. In terms of the subjects’ educational background, the sample was composed of 445 students from Secondary Schools (of the 51.7%, 53.5% had scientific training and 46.5% had liberal arts training) and 415 university students (of the 48.3%, 47.3.5% from Liberal Arts and 52.7% from the Sciences). All the educational institutions are in the municipality of Naples. The subjects of the study, who had complete anonymity in their responses, freely participated under law N. 675/96. The sample is stratified (Bazan, Osorio, 2007). Instrument The Italian version of the AQ was used, composed of 29 items focused on evaluating physical aggression (9 items), verbal aggression (5 items), rage (7 items) and hostility (8 items), coded on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 represented entirely false for me and 5 represented entirely true for me. Statistical Analyses To verify the four-factor correlated model, proposed by Buss and Perry (1992) and then confirmed (Garcia-León et al., 2202; Fossati et al., 2003; Gerevich, Bácskai, Czobor, 2007), a Confirmatory Factor Analysis was run relying on the Lisrel 8.51 software (Jöreskog e Sörbom, 1993). To evaluate the gap between the reproduced matrix and the observed matrix, the research relied on the rapport between both the Chi-square test and degrees of freedom, since the former is not reliable when used with numerous samples as in the present study. The following indexes were also used: Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Standardized Root Mean square Residual (SRMS), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) and Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI). An Exploratory Factor Analysis was subsequently conducting with SPSS.16 software, using the Principal Axis Factorization method (Oblimin rotation with Kaiser Normalization) and a Principle Components Analysis (Oblimin rotation with Kaiser Normalization). Using the same software, internal coherence was verified with Cronbach’s α values, and Variance Analyses were run to verify the existence of statistically significant differences in mean scores among sub-traits in relation to subjects’ gender and age – the latter defined based on enrollment in Secondary School or University. Results Validation of the Italian version of the AQ The results of the analysis (Table 1) showed unsatisfactory values for each of the indexes considered therefore verifying the two-dimensional correlated model developed by Williams et al. (1996), a study that considers physical aggression together with rage and verbal aggression with hostility. The results derived from the application of this model indicate a deterioration of all indices taken into consideration. Tab. 1. Four and two dimensions models presentation Model χ2/df RMSEA NFI NNFI CFI SRMR GFI AGFI Four-factors model (Buss e Perry, 1992) 5.10 .07 .71 .74 .76 .07 .87 .85 Two-dimensions model (Williams et al., 1996) 8.48 .09 .60 .61 .64 .085 .80 .76 Confirming the inadequacy of models in the current literature with respect to the data collected in our study, we continued with an Exploratory Factor Analysis (Principle Axis Factorization method, Oblimin rotation with Kaiser Normalization). The scree test reading indicated the need to extract three factors and the saturation analysis led to the subsequent elimination of six items with saturations inferior to ±30 or with elevated saturations of more latent traits (2 – “I tell my friends openly when I disagree with them”; 3 – “I flare up easily, but get over it quickly”; 7 – “When frustrated, I let my irritation show”; 10 – “When people annoy me, I tell them what I think of them”; 22 – “I have trouble controlling my temper”; 23 – “I am suspicious of overly friendly strangers”). The final result was composed from 23 items that collectively explain the overall 33.02% variance. As demonstrated in Table 2, the first factor (20.61% variance) mirrors the functional or motor subcomponent of aggressive behavior and can be entirely assimilated to the “physical aggression” trait; the second factor (8.0% variance) captures cognitive competence with the “hostility” trait items; the third factor (4.41% variance) is primarily composed of a mixture of items – negative signs – originally directed at the functional or motor subcomponent (verbal aggression) and at the emotional subcomponent (rage), therefore read as the “unsuccessful verbalization of rage.” Moreover, considering the correlation among the latent structures is became clear that the unsuccessful verbalization of rage trait is significantly correlated (.01, bilateral test) with physical aggression (.48) and hostility (.35), the latter being significantly correlated (.01, bilateral test) with physical aggression (.23). Tab. 2. Exploratory Factor Analysis % variance Cronbach’s α Physical Aggression 5 Given enough provocation, I may hit another person 21 There are people who pusher me so far that we came to blows 1 Once in a while I can’t control the urge to strike another person 9 If somebody hits me, I hit back 27 I have threatened people I know 17 If I have to resort to violence to protect my rights, I will 29 I have become so mad that I have broken things 24 I can think of no good reason for ever hitting a person Hostility 16 I wonder why sometimes I feel so bitter about things 26 I sometimes feel that people are laughing at me behind my back 8 At times I feel I have gotten a raw deal out of life 12 Other people always seem to get the breaks 11 I sometimes feel like a powder keg ready to explode 20 I know that “friends” talk about me behind my back 28 When people are especially nice, I wonder what they want 4 I am sometimes eaten up with jealousy Unsuccessful Verbalization of Rage 18 My friends say that I’m somewhat argumentative 14 I can’t help getting into arguments when people disagree with me 13 I get into fights a little more than the average person 19 Some of my friends think I’m a hothead 15 I am an even-temperated person 6 I often find myself disagreeing with people 22 Sometimes I fly off the handle for no good reason 1 2 3 20.61 8,00 4,41 .80 .72 .77 Item-total correlation α if item is eliminated .82 .72 .62 .60 .52 .49 .44 .33 .00 .07 .03 -.05 .03 .10 .19 -.07 .07 .04 -.08 .04 -.06 -.05 -.09 -.02 .70 .64 .59 .49 .50 .47 .45 .29 .75 .75 .77 .78 .78 .78 .79 .81 -.11 .02 -.01 -.04 .09 .11 .08 -.01 .65 .62 .59 .55 .47 .39 .36 .31 .06 .04 .07 .00 -.07 -.01 -.09 -.09 .50 .51 .46 .46 .42 .34 .36 .28 .68 .67 .68 .68 .69 .71 .70 .72 -.05 -.01 .13 .22 .14 -.12 .11 -.05 -.06 .03 -.01 -.06 .16 .24 -.75 -.63 -.58 -.45 -.45 -.43 -.40 .61 .50 .58 .49 .44 .35 .47 .71 .74 .72 .74 .75 .77 .75 The resulting internal coherence was satisfactory considering: physical aggression (α .80), hostility (α .72) and the unsuccessful verbalization of rage (α .77). It should be highlighted that the exploratory procedure adopted by some researchers (Bryant, Smith, 2001; Garcia-Léon, et al., 2002; Gerevich, et al., 2007) is slightly but significantly different from that just described. In particular, appeal is generally made to Principle Component Analysis (PCA), with some exception (Buss, Perry, 1992). This is not considered a Exploratory Factor Analysis since it is a technique whose goal is summarizing information contained a totality of observed variables and not arriving at the identification of latent constructs. This is achieved by applying the method of principle factors or Principle Axis Factorization, regression analysis or maximum likelihood estimation (cf. Luccio & Paganucci, 2007; Giannini & Panocchia, 2006). Despite the inadequacy of PCA to reach our objectives, for the purposes of comparison, we chose to repeat the analysis adopting the PCA along with Oblimin rotation and Kaiser Normalization (Table 3). On the basis of the scree test analysis, the four-trait structure was confirmed even with the necessary elimination of six items (7, 9, 11, 20, 23, 25) on the basis of saturation analysis. The final solution, including 23 items, explains the 44.59% total variance, but the distribution of the items among the four factors is distinct from Buss and Perry (1992): while the first two traits (physical aggression and hostility) are completely represented by relative items, the other two are composed from a mixture of items that originally referred to verbal aggression and rage. Moreover, the four factors remain significantly interrelated. Tab. 3. Principal Components Analysis 1 2 % variance 22,09 9,72 Cronbach’s α .78 .67 Physical Aggression Item 5 .79 .01 Item 21 .77 .05 Item 1 .68 .02 Item 27 .65 .00 Item 17 .61 .10 Item 29 .55 .18 Item 24 .43 -.13 Hostility Item 16 -.09 .72 Item 8 .02 .68 Item 12 .00 .66 Item 26 .08 .66 Item 4 -.02 .46 Item 28 .11 .43 Verbal Aggression/Rage1 Item 18 -.05 -.04 Item 14 -.05 -.08 Item 13 .19 .03 Item 6 -.19 .14 Item 15 .18 -.11 Item 19 .27 -.04 Item 22 .12 .26 Verbal Aggression/Rage2 Item 2 -.07 -.11 Item 10 .15 .01 Item 3 .02 .13 3 4 7,37 5,41 .77 .44 Item-total correlation α if item is eliminated -.07 -.03 .05 .09 .05 .08 -.01 .15 .04 .12 -.15 -.08 .00 .02 .65 .64 .59 .51 .46 .46 .27 .72 .72 .74 .75 .76 .76 .80 -.05 -.06 -.01 .04 .03 .09 .02 -.05 .01 -.20 .17 .05 .47 .44 .47 .45 .29 .32 .61 .62 .61 .62 .67 .66 .80 .69 .65 .59 .55 .49 .46 .03 .15 -.07 -.01 -.05 .05 .07 .61 .50 .58 .35 .44 .49 .47 .71 .74 .72 .77 .75 .74 .75 .01 -.03 .14 .79 .74 .41 .33 .32 .18 .27 .24 .53 On the basis of this factor solution, we evaluated the reliability of the scale in relation to the exactness or precision with which the entire scale and the individual sub-scales could estimate the different levels of the various components making up aggressive behavior. Although the first three sub-scales present a satisfactory internal coherence (respective α values of .78, .67 and .77), the final sub-scale presents an unsatisfactory internal coherence index (α .44). On the basis of our results, considering indications from the methodological literature (Pannocchia & Giannini, 2007; Fabrigar, Mac-Callum, Wegener & Strahan, 1999), the solution obtained by applying Exploratory Factor Analysis with Principle Axis Factorization was considered more pertinent. We consequently proceeded to confirm and verify this structure (Figure 1). The indexes to adjust the model to the data can be considered satisfactory [χ2/df = 4.19; RMSEA = .06; NFI = .82; NNFI = .84; SRMR = .06; GFI = .91; AGFI = .89]. Subjects’ differentiation on the basis of age and gender The descriptive analyses for this three-dimensional model demonstrate mean scores not particularly elevated across the scale, as with the sub-scales (Table 4). Fig. 1. Model Graph 0.67 5 1.00 21 0.62 1 1.50 9 0.95 27 1.11 17 1.36 29 1.78 24 1.12 16 1.10 26 1.27 8 0.99 12 1.24 11 1.48 20 1.39 28 1.64 4 1.04 18 1.14 14 0.75 13 1.09 19 1.22 15 0.92 6 1.22 22 1.02 1.01 0.74 0.85 Physical Aggression 1.00 0.64 0.68 0.73 0.46 0.26 0.76 0.75 0.77 0.67 Hostility 1.00 0.69 0.56 0.55 0.47 0.41 0.89 0.74 0.80 0.76 0.66 0.42 0.77 Unsuccessful Verbalization of Rage 1.00 0.59 Tab. 4. Total scale and sub-scales mean scores Means 2.30 2.54 2.81 2.54 Physical Aggression Hostility Unsuccessful Verbalization of Rage Scale Total The variance analysis (Table 5 and Table 6) shows that mean scores of physical aggression and hostility are higher in males, while among females the unsuccessful verbalization of rage was higher. While mean scores of physical aggression, hostility and the unsuccessful verbalization of rage are higher in younger subjects, frequently Secondary School students, these scores are lower in older subjects. Tab. 5. ANOVA dimensions x sexual gender Physical Aggression Hostility Unsuccessful Verbalization of Rage Male 2,73 2,61 2,69 Female 1,99 2,49 2,89 Tab. 6. ANOVA dimensions x age (High Schools/Universities) Univ. High.Sch. Physical Aggression 2,11 2,46 Hostility 2,48 2,59 Unsuccessful Verbalization of Rage 2,72 2,89 F 195,716(1,858) 4,635(1,858) 14,925(1,858) F 36,751(1,858) 3,957(1,858) 10,956(1,858) Sig. 0,000 0,032 0,000 Sig. 0,000 0,047 0,001 Discussion In terms of the components validity, the results of the confirmatory factor analyses show that the Italian version of the AQ, the four-factor structure, which was confirmed in other countries (Ando et al., 1999; Bernstein, Gesn, 1996; Bouchard, 2007; GallardoPujol et al., 2006; Garcia-Léon et al., 2002; Meesters et al., 1996; Morren, Meesters, 2002; Rodríguez, Peña, Graña, 2002; von Collani, Werner, 2005), does not hold true with our sample. The quality of this instrument is proven by its clear and distinct evaluation of the functional or motor component of aggressive behavior (physical aggression); the emotional component (rage) remains linked to the other functional or motor subcomponent (verbal aggression), similarly to the cognitive component (hostility). Such contextual specificity leads us to consider that in Southern Italy the emotional component of aggressive behavior is rooted in its verbal expression, therefore giving rise to a single trait and bringing back an item originally ascribed to physical aggression (“I get into fights a little more than the average person”). This last data in particular leads us to consider that the subjects’ reading of this item reveals an ulterior contextual specificity; among our subjects, picking a fight is read as a verbal-expressive aspect of rage without physical externalization. The results also show that the validity of the AQ overall is satisfactory as are the three sub-scales that make it up, although each in a different measure. In particular the functional or motor sub-component of aggressive behavior (physical aggression), has the highest Cronbach’s α values while the cognitive component (hostility) has the least elevated although still satisfactory. In line then with the original study by Buss and Perry (1992), and just as the studies conducted in other countries which evaluated the psychometric characteristics of the AQ (Bouchard, 2007; Bernstein, Gesn, 1997; Harris, 1995, 1997; Nakano, 2001; Rodríguez, Peña, Graña 2002; Vigil-Colet et al., 2005), it is possible to confirm that the Italian version of the AQ also shows sufficient validity. As the authors of the original version have confirmed, however, we can therefore demonstrate that, although with necessary differences, even with the southern Italian sample, the AQ is a psychometric instrument that provides sufficient empirical evidence and bases its precision on theoretical validity in the evaluation of different types of aggression (Buss, Perry, 1992). Moreover, as has come out of previous works (Bryant, Smith, 2001; Gerevich, Bácskai, Czobor, 2007; Morales-Vives, Codorniu-Rada, Vigil-Colet, 2005; Nakano, 2001; Ramirez, Andreu, Fujihara, 2001; Vigil-Colet et al., 2005), our analyses also show that the exclusion of some items from the overall scale produces an improved factor model. Regarding the effects of the age and gender variables on different types of aggression, we must underscore how the results obtained partially mirror those obtained by other authors, even in different contexts (Buss, Perry, 1992; Sommantico et al., in press; Fossati et al., 2003; Harris, 1995, 1997; Meesters et al., 1996; Nakano, 2001; Rodríguez, Peña, Graña 2002; von Collani, Werner, 2005). In general terms, even though mean scores were not very high, men tend to show greater levels of aggression, specifically physical and proportional to the verbal expression of rage. In line with the cited studies and the literature on this specific phase of the life (Greenspan, Pollock, 1991; Bergeret et al., 1985), the increased age of the subject contributes to a decrease in the different types of aggression. On the other hand, women show lower levels in the verbal expression of rage. In conclusion, in our subjects, hostility, generally ascribed to women, demonstrates higher average means in males. References Ando, A., Soga, S., Yamasaki, K., Shimai, S., Shimada, H., Utsuki, N., Oashi, O., Sakai, A. (1999). Development of the Japanese version of the Buss-Perry AQ(BAQ). Shinrigaku Kenkyu, 70, 384-392. Ang, R. (2007). Factor structure of the 12-item aggression questionnaire: Further evidence from Asian adolescent samples. Journal of Adolescence, 30 (4), 671-685. Bazán, R. G. y Osorio, G. M. (2007). Manual de muestreo. En M. Chávez Becerra. Métodos Cuantitativos. México: Ediciones FES Iztacala UNAM. Bergeret, J., Cahn, R., Diatkine, R., Jeammet, P., Kestenberg, E., Lebovici, S. (1985). Adolescence terminée, adolescence interminable, Paris: PUF. Bernstein, I.H., Gesn, P.R. (1997). On the dimensionality of the Buss/Perry Aggression Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 563-568. Bouchard, J. (2007). Validation de la version française du AQauprès de deux échantillons: étudiants universitaires (étude1) et adultes non-recrutés en milieu universitaire (étude 2). Mémoire de Maitrise en Psychologie, Université du Québec à Chicoutimi. Bryant, F.B., Smith, B.D. (2001). Refining the architecture of aggression: a measurement model for the Buss-Perry aggression questionnaire. Journal of Research on Personality, 35, 138-167. Buss, A.H., Durkee, A. (1957). An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostility. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 21. 343-349. Buss, A.H., Perry, M. (1992). The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 452-459. Fabrigar, L., Maccallum, R.C., Wegener, D., Strahan, E. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4 (3), 272-299. Fossati, A., Maffei, C., Acquarini, E., Di Ceglie, A. (2003). Multigroup confirmatory component and factor analyses of the Italian version of the Aggression Questionnaire. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19 (1), 54-65. Gallardo-Pujol, D., Kramp, U., García-Forero, C., Pérez-Ramírez, M., Andrés-Pueyo, A. (2006). Assessing aggressiveness quickly and efficiently: the Spanish adaptation of Aggression Questionnaire-Refined version. European Psychiatry, 21 (7), 487-494. Garcia-León, A., Reyes, G.A., Vila, J., Pérez, N., Robles, H., Ramos, M.M. (2002). The Aggression Questionnaire: a validation study in student samples. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 5, 45-53. Gerevich, J., Bácskai, E., Czobor, P. (2007). The generalizability of the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 16 (3), 124-136. Giannini, M., Panocchia, L. (2006). L’analisi fattoriale esplorativa in psicologia. Una guida pratica per la ricerca. Firenze: Giunti O.S. Greenspan, S.I., Pollock, G. (Eds) (1991). The Course of Life. Vol. IV. Adolescence. Madison: International Universities Press. Harris J.A. (1995). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Aggression Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33 (8), 991-993. Harris, J.A. (1997). A further evaluation of the Aggression Questionnaire: Issues of validity and reliability. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35 (11), 1047-1053. Jöreskog, K.G., Sörbom, D. (1993). Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Chicago: Scientific Software International, Inc. Luccio, R., Paganucci, C. (2007). Analisi fattoriale esplorativa e analisi delle componenti principali: un tentativo di guida dei perplessi. Bollettino di Psicologia Applicata, 251, 3-12. Maffei, C. (2008). Versione italiana dell’AQ(AQ). In, C. Maffei, Borderline. Struttura, categoria, dimensione. Milano: Cortina. Meesters, C., Muris, P., Bosma, H., Chouten, E., Beuving, S. (1996). Psychometric evaluation of the Dutch version of the Aggression Questionnaire. Behavioral Research and Therapy, 34 (10), 839-843. Morales-Vives, F., Codorniu-Raga, M.J., Vigil-Colet, A. (2005). Caracteriricas psicométricas de las versiones reducidas del Cuestionario de Agresividad de Buss y Perry. Psicothema, 17 (1), 96-100. Morren, M., Meesters, C. (2002). Validation of the Dutch version of the AQin adolescent male 405 offenders. Aggressive Behavior, 28, 87-96. Nakano, K. (2001). Psychometric evaluation of the Japanese adaptation of the Aggression Questionnaire. Behavioral Research and Therapy, 39, 853-858. Panocchia L., Giannini, M. (2007). Valutazione dell’uso dell’analisi fattoriale esplorativa nella ricerca psicologica in Italia. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia, 34, 391-406. Parrello, S., Aleni Sestito, L., Nasti, M.G., Sica, L.S. (2008). Redefinition of self-others system in the transition to emerging adulthood: a narrative approach. EARA, European Association for Research on Adolescence. Torino, Maggio 2008. Ramirez, J.M., Andreu, J.M., Fujihara, T. (2001). Cultural sex differences in aggression: a comparison between Japanese and Spanish students using two different inventories. Agrressive Behaviour, 27, 313-322. Rodríguez, J.M., Peña, E., Graña, J.L. (2002). Adaptación psicométrica de la version española del Cuestionario de Agresión. Psicothema, 14 (2), 476-482. Santisteban, C., Alvarado, J.M., Recio, P (2007). Evaluation of a Spanish version of the Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire: Some personal and situational factors related to the aggression scores of young subjects. Personality and Individual Differences, 42 (8), 1453-1465. Sierra, J.C., Gutiérrez, Q.J.R. (2007). Validación de la versión española del Cuestionario de Agresión de Buss-Perry en Estudiantes Universitarios Salvadoreños. Psicología y Salud. 17, 1, 303-313. Sommantico, M., Osorio Guzmán, M., Parrello, S., De Rosa, B. (in press). Significado de las funciones familiares en adolescentes italianos. nuevas fronteras entre paterno y materno. Revista Colombiana de Psicologia, 17. SVIMEZ (2008). Rapporto 2008 sull'economia del Mezzogiorno. Bologna, Il Mulino. Vigil-Colet, A., Lorenzo-Seva, U., Codorniu-Raga, M.J., Morales, F. (2005). Factor structure of the AQamong different samples and languages. Aggressive Behavior, 31 (6), 601-608. von Collani, G., Werner, R. (2005). Self-related and motivational constructs as determinants of aggression. An analysis and validation of a German version of the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 38, (7), 1631-1643. Williams, T.Y., Boyd, J.C., Cascardi, M.A., Poythress, N. (1996). Factor Structure and Convergent Validity of the AQin an Offender Population. Psychological Assessment, 8 (4), 398-403.