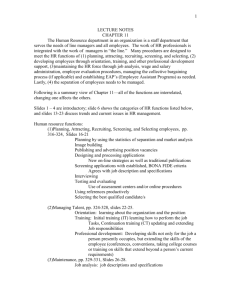

Chapter 2 - PAKISAMA Mutual Benefit Association, Inc.

advertisement