Coker Gets Going! - Fiction Novel Excerpt

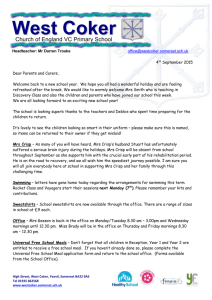

advertisement