An International Case Study of Contemporary Practice

advertisement

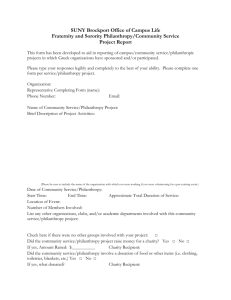

Entrepreneurial Philanthropy: An International Case Study of Contemporary Practice Lead Author: Dr Jillian Gordon Contact Details: University of Strathclyde, Strathclyde Business School, Hunter Centre for Entrepreneurship, 199 Cathedral Street, Glasgow, G4 OQU, Scotland. Tel: 0141 548 3482. Email: jillian.gordon@strath.ac.uk. www.strath.ac.uk/huntercentre Co-Authors: Professor Eleanor Shaw, University of Strathclyde, Strathclyde Business School Professor Mairi Maclean, University of Exeter Business School Professor Charles Harvey, Newcastle University Business School Introduction Philanthropy is a key activity of wealthy entrepreneurs (Gordon, 2011; Shaw et al., 2013; Harvey et al., 2011; Maclean et al., 2013; Acs, 2013) motivated by the opportunity and capacity to support economic and social regeneration in regions that can benefit from intervention. High net worth entrepreneurs are increasingly focussing on engaging in philanthropy at a younger age; an act made possible by their capacity to amass significant personal fortunes from their entrepreneurial success (Bishop and Green, 2008, Handy and Handy, 2006; Gordon, 2011; Shaw et al., 2013). Many of the new philanthropists focus their attention on developing countries where they are actively trying to orchestrate change amidst a myriad of complex factors (Bishop and Green, 2008; Brainard and LaFleur, 2008). The solutions being championed by entrepreneurial philanthropists often involve the fostering of private enterprise (De Lorenzo and Shah, 2007) and the strengthening of existing enterprise and market infrastructure. The capacity of such individuals to create change is made possible because of their individual capital wealth (economic, social, cultural and symbolic); and their positioning within a macro network that spans the domains of business, politics, government and international development (Gordon et al., forthcoming). In particular, the African continent has become the focal point of many entrepreneurial philanthropists in recent years. The potential of philanthropists to engage in activity in this region, which is both strategic and a potential game changer at a macro level, is noticeable, especially if we consider the profile of individuals like Bill Gates and Sir Richard Branson and their command of resources: wealth, knowledge, reputation and contacts. The philanthropic presence of such individuals in the region is noted and forever present in contemporary media. However, little is known about the practices of entrepreneurial philanthropy in this context. Recent extant literature has sought to provide an introduction to entrepreneurial philanthropy within a theoretical framework using Bourdieu’s capital theory (Harvey et al., 2011; Shaw et al., 2013). Building on such research, this paper seeks to extend our knowledge and understanding of entrepreneurial philanthropy by exploring the practical workings of the phenomena. Specifically, this paper explores entrepreneurial philanthropy in an international context; through a single case study of the philanthropic activity of the Wood Family Trust (WFT), established by Sir Ian Wood and his wife Lady Helen, in 2007, with an endowment of £50 million. Sir Ian Wood is a successful Scottish entrepreneur whose wealth derives from the family business, the Wood Group. Under Sir Ian’s control, the Wood Group has grown to be one of the most successful engineering companies in the world. Today, the re-named, Wood Group PSN employs over 35,000 people around the globe in the oil and gas and power generation markets; providing services in engineering, procurement and construction management. In particular, we are interested in the work of the WFT in Sub Saharan Africa, where it targets 75% of its overall philanthropic investment at the region. More specifically, philanthropic investment is targeted at the tea sector in the countries of Tanzania and Rwanda. The other 25% of the WFT’s investment is targeted at young people in the UK, helping them to become more enterprising, independent, tolerant and caring members of society. This paper, however, is solely focused on the international activities of WFT in the tea sectors of Tanzania and Rwanda. This paper adds to the relatively sparse but growing literature on entrepreneurial philanthropy (De Lorenzo and Shah, 2007; Gordon, 2011; Harvey et al., 2011; Shaw et al., 2013; Maclean et al., 2013) and responds to a call for more research which relates entrepreneurship to its societal context. It also relates to the recent work of Acs (2013), who argues that entrepreneurship and philanthropy are inextricably linked, and who posits that philanthropy has given an edge to capitalism by promoting fundamental forces that are necessary to advance technological, social and economic equality. Building on the work of Acs (2013), we emphasize the importance of embeddedness and the sociocultural context in which social innovation and economic development occur (Austin et al, 2006; Granovetter, 1985; Ram et al, 2008; Smith and Stevens, 2010; Tapsell and Woods, 2010; Maclean et al., 2013). We adopt a case- based approach (Eisenhardt, 1989; Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007; Yin, 2009) to examine how entrepreneurial philanthropy can support and foster enterprise and market infrastructure that can cultivate economic development in developing countries, in a meaningful way, and help towards revitalizing a region marred by poverty and low economic growth. The paper is situated within a wider and on-going study of entrepreneurial philanthropy, which examines individual and business giving in contemporary, historic and international contexts. We define entrepreneurial philanthropy as the pursuit on a not-for-profit basis of big social objectives through active investment of their economic, social, cultural and symbolic resources (Harvey et al., 2011; Maclean et al., 2013; Shaw et al., 2013). Entrepreneurial philanthropists are characterised by their desire to amass huge levels of personal wealth which they choose to assign a large share of to their philanthropic endeavours (Schervish et al., 1994; Bishop and Green, 2008; Shaw et al, 2013; Maclean et al, 2013). Moreover, entrepreneurial philanthropy moves beyond traditional forms of philanthropy where donations and grants are the norm (Anheier and Leat, 2006).The present paper uses the Wood Family Trust (WFT) as a lens through which to examine the contemporary practice of entrepreneurial philanthropy in an international context, and specifically focuses on the work of WFT in the agricultural sector of Tanzania and Rwanda. We ask the following questions: how is entrepreneurial philanthropy practiced; what does it add that other forms of donor giving does not; how does it add, more generally, to current debates on the role of philanthropy in economic development and what are the implications for practice and policy. The paper is structured as follows. In the next section we set out the context of the study and make linkages to relevant literature, before presenting the research setting and our methodology. The empirical findings of the case study are then presented and discussed. To conclude, we outline the main conclusions of the paper, its limitations and the implications for policy and practice. Context: Agriculture Sector, Value Chains and Economic Development in Sub Saharan Africa The importance of the agriculture sector to the economic development of East African countries cannot be underestimated. In Sub Saharan Africa, 64% of the population depend on agriculture for their livelihood and income (Best et al., 2005). Hence improvement in the agriculture sector has the potential to make a real impact on the development of the national economies within the Sub Saharan region. Moreover, the development of a more efficient agricultural sector can positively impact on the economic opportunities and well being of the rural populous (Minot and Vargas Hill, 2007). Generally, East African countries are characterised by below average harvests, elevated food prices, conflict and food insecurity [a consequence of regional droughts and historic conflicts that have marred the region]. In Tanzania, a country with a population of 42.7 million people, of which 74% are rural in population; agriculture represents 28% of Tanzanian GDP and over 80% of the labour force are based in agriculture (World Development Report, World Bank 2005). The agriculture sector is of real significance to Tanzania; and by choosing to focus on the sector the WFT has the potential to create positive change that will benefit Tanzania top down and bottom up. Economic policy in East African countries has been geared towards decreasing the central role of government and creating a more liberal economy, a consequence of their attained independence and their former socialist roots (Impact Investment Report, Gatsby Charitable Foundation, 2011). Elsewhere, we can observe that where there is strong agricultural productivity, there is typically a faster rate of economic growth; which benefits the poor (Minot and Vargas Hill, 2007). Over the last decade there has been increasing interest in ‘making markets work for the poor’ (Elliot et al., 2008), a particular approach to economic and social development that focuses on strengthening market systems that benefit the poor. It is against this backdrop that specific sector value chains become of interest. The value chain as a concept was first introduced by Porter (1985). It focuses attention, as the metaphor suggests, on the linked set of activities through which the enterprise can accrue value and thereby competitive advantage (Gereffi et al., 2001) By focussing on the complete chain of a 4 sector and determining where and how value can be added and how it can be made efficient brings an opportunity to create positive socio-economic change. Strengthening the value chains in the agricultural sector becomes significant, because small holder farmers who feature in the agricultural chain have typically been ignored despite their contribution to food security and income in the region (Jayne et al., 2003). The World Bank notes that achieving a 1% increase in agricultural yield is estimated to reduce the percentage of people living on less than $1 a day by between 0.6% and 1.2% (World Bank, 2005); making a positive impact on the income and food security of households. By focussing on the strengthening of value chains in sub-sectors of the agricultural sector and supporting them to become more productive and efficient, the effects are considered to be potentially far and wide reaching (and more sustainable) for people living in-country (Ponte and Gibbon, 2005). Moreover, by creating a better equipped agricultural sector the capacity of the sector overall to attract further private investment can potentially be strengthened. In turn, the availability of private investment can support the growth of the private sector and that of SMEs; who are critical to the overall growth and development of any country (Wennekers and Thurik, 1999). By choosing to focus on a specific sector, value chains, private sector and smallholders the links to entrepreneurship become important. More specifically, the success and experience of the individual philanthropist in entrepreneurship is viewed here as critical to the approach adopted in philanthropy; which aims to improve livelihoods through business. This resonates with Stayert and Katz’s (2004) discussion on entrepreneurship, who posit that it has become a model for innovative thinking, reorganising the established and crafting the new across alternative space and settings (2004:182). Philanthropy is a space whereby entrepreneurs can extend their innovative thinking, practices and expertise in a disruptive but innovative manner (Gordon, 2011, Shaw, et al., 2013). The socio-cultural context of entrepreneurship is therefore critical to entrepreneurial philanthropy; it transfers over to the philanthropic activities of such individuals, it informs and influences what they choose to focus on and how they engage in their philanthropy. Thus entrepreneurial values and practices are inherent to how entrepreneurial philanthropy is practiced (Shaw et al., 2013). The approach adopted in entrepreneurial philanthropy goes beyond simply donating money or awarding a grant passively; entrepreneurial philanthropy involves the active involvement of entrepreneurs in their philanthropy; who draw on the totality of their resources to stimulate socio-economic innovation (Gordon, 2011; Shaw et al., 2013). Research Setting and Research Process The empirical foundation of this paper is an in-depth case study of the WFT. In the seminal paper on case research, Eisenhardt (1989) argues that as a research strategy it is appropriate when used to explore new topics, and where existing theory is inadequate. Moreover, Eisenhardt argues that case research is a valuable method when attempting to develop an understanding of dynamics within a specific setting. WFT has been purposefully selected (Siggelkow, 2007) because of its endeavours in Africa, it represents a rare opportunity to explore the practices of entrepreneurial philanthropy in an international context. As highlighted by Perrini et al., (2010) and Eisenhardt and Graebner (2007), access can also determine the selection of a case study. As research into socially innovative entrepreneurial philanthropists is dependent on securing access, the opportunity to secure access and to conduct research into WFT was considered valuable to extend our understanding of the phenomenon of entrepreneurial philanthropy. Research Setting: Biography of the organisation Greenwood and Hinings (1993) argue for the need to understand the biography of an organisation under research. The WFT was founded in 2007 by Sir Ian Wood and his wife Lady Helen with an endowment of £50 million, and is headquartered in Aberdeen, alongside that of the commercial business. WFT has two main objectives. The first is to make markets work for the poor in Sub Saharan Africa. The second objective is to encourage young people to become enterprising, independent, tolerant and caring members of society. In relation to the first objective, WFT advocate providing a framework for people to help themselves, which they further articulate as being centred on wealth creation, job creation and business development. WFT invests multiple resources in the programmes it supports. Within the activities of WFT, we focused in particular our research on its international programmes in the Tea Sector. In Tanzania, WFT along with the Gatsby Charitable Foundation (GCF) [the philanthropic vehicle of Lord Sainsbury] implement the ‘Chai-Kwa Maendeleo ya Tanzania’ (Chai) programme and the ‘Imbarutso-Win Win for Rwandan tea programme’ (Imbarutso). Chai is the kiswhaili word for tea. The Chai programme was launched in 2009 with a commitment to invest US $9 million, with a specific aim to double smallholder tea production, increase farmer profits and increase the competitiveness of the Tanzanian tea sector. Tea represents the fourth largest export crop in Tanzania and is worth US$28.7 million in export earnings to the country. The Imbarutso programme was launched in 2011 with a commitment to invest US$9 million over a six year period in the Rwandan tea sector. Imbarutso is the Kinyarwanda word which means to catalyse. The Imbarutso programme aims to increase smallholder net income, turn smallholder farmers into viable and efficient micro and small enterprises (MSE’s) and increase the overall effectiveness of the tea sector. Tea represents Rwanda’s second highest export earner and is considered to be one of the highest quality tea type in the world; it represents a vital source of income for around 30,000 smallholder businesses and 60,000 households. The overarching theme across both tea programmes is to help economic development at a micro and macro level by helping people to help themselves. The partnership with GCF is symbolically important given the historic presence of GCF in the region and the status of its founder. GCF has actively promoted economic development in the region for 18 years; and has programmes in the cotton, textile and tea sectors. GCF has also provided venture capital for African agriculture since 2005. WFT leads on both the Chai and the Imbarutso programmes but in full consultation with GCF. The ethos of WFT in its African activities is best illustrated in the following excerpt taken from the latest Chairman’s Review: “Our role is to facilitate employment and business activities through supporting local enterprise and market development in growth sectors. We analyse sector value chains and unblock key constraints from primary production through to processing, distribution, and eventually to the end market and consumer” (WFT Chairman’s Review Report, 2012). The centrality of community (in both a geographic and vocational sense) and the socio-cultural context is observable in the philanthropic approach adopted by WFT to catalyse social and economic innovation in the region. Peredo and Chrisman (2006) and Steyaert and Katz (2004) both argue that the renewal and maintenance of communities and the creation of opportunities are pivotal to helping people to help themselves. Moreover, the surrounding environment [in this instance the in-country government, trade sector associations and farmers] needs to be amenable to socially innovative ideas in order to effect change (Maclean et al., 2013; Chell et al., 2010; Smith and Stevens, 2010; Steyaert and Katz, 2004). Thus building and maintaining strong relationships within the sector, in-country, is paramount to the future success of philanthropic intervention. Since its inception in 2007 WFT has spent a sum of £13 million on the programmes it supports in the UK and in Africa; at the same time the funds of the Trust have increased considerably. At the beginning of 2013 WFT held funds of around £113 million to continue engaging in the existing programmes in the UK and in Africa (WFT Annual Review Document, 2012, WFT Audited Accounts, 2012). During the 2011/2012 financial year WFT committed £835,000 to Chai and £359,000 to Imbarutso (WFT Annual Review Document, 2012; WFT Audited Accounts 2012). The Chai programme is now nearing its fourth year of implementation and over the course of the three years that audited accounts are available; WFT has invested £1.97 million in the Chai programme.1 1 Figure deduced from the 2009/10, 2010/11, 2011/12 WFT Annual Report and Accounts. 6 Research process In conducting our empirical investigation, in-depth semi-structured life-history interviews with key individuals of WFT were conducted by one member of the research team over a six-month period. The interviewees included the philanthropist, the chief executive of the foundation, the operational director of African programmes and the head of Africa operations at GCF. The interviews lasted between 90 minutes and two hours in length, all were recorded and transcribed. The WTF interviewees were conducted face to face at the Scottish Headquarters of WFT and the GCF interview was conducted by telephone with follow up communication conducted via email. Further sources of empirical evidence included annual reports, individual programme reports, and other relative documents. . The life-history interviews provided rich and meaningful insights into the working practices of WFT, it importantly allowed for the personal experience of each individual’s engagement in the work of WFT to be illuminated. In developing the case study the research team were guided by Eishenhardt and Graebner’s (2007) suggestion to collect interview data using various, knowledge intensive informants each from a different hierarchical level and function within an organisation, as well as from within associated organisations. The adopted approach has allowed for the multiple personal stories to be explored, the organisation as a unit of analysis to be explored and the organisational partnership with GCF to be explored; it therefore sits within Perren and Ram’s paradigmatic framework (2004) which is considered particularly suited to entrepreneurship research. The inductive approach has allowed for evidence base to be developed that enables us to explore the practical workings of entrepreneurial philanthropy; and provides us with valuable insights from the different actors involved. Findings Philanthropic Ethos “We believe we will only effect change by helping local people and communities to help themselves in a way that is consistent with their culture and way of life. Money alone cannot realise the vision, but effective application of market analysis, quality minds, effective delivery partners and local private enterprise will, we believe create sustainable change” (Sir Ian Wood, Philanthropist).2 The above quote clearly articulates the philanthropic ethos of WFT and is aligned with the findings of the wider study of entrepreneurial philanthropy. The anchor of private enterprise in entrepreneurial philanthropy is strong, and in this particular case it is viewed as being fundamental to developing a culture of self help. Through their activities in Tanzania and Rwanda, WFT and GCF are actively engaged in their philanthropy; and embedded into the socio-economic environment through their on the ground presence, by a team of highly skilled and highly networked individuals who manage and drive forward the programmes on the ground. “We are a hybrid donor, we are the one funding the projects but we are also overseeing a portfolio of activities. Some of those we tender out, some of those we will hire and bring in others, some we will engage directly with the private sector. Having a presence can make us assured that we are more in touch with what industry wants and we can be honest. If things go wrong, we can say things have gone wrong and we can put the brakes on and back up and look at how to respond” (Head of African Operations, WFT). Flexibility and open-mindedness are key components of the philanthropic ethos as illustrated in the previous quote. 2 An excerpt from the WFT Chairman’s Review 2012. Operational Infrastructure WFT in the UK is a lean operation, it is non bureaucratic, and young in dynamics. Importantly, it is married with the mature business acumen, wisdom and expertise of the entrepreneurial philanthropist, Sir Ian Wood. WFT is resourced by a small team of people led by the chief executive Jo Mackie, the team is split into UK based programmes and Africa based programmes. WFT has set up a wholly owned subsidiary, WFT Africa, to manage its affairs in Africa. WFT Africa is a company by guarantee with charitable status and is headquartered in Kenya, which is viewed as the anchor economy of East Africa. Early on in the philanthropic journey WFT recognised the importance of having representatives on the ground in Africa if they are to be effective in their African philanthropy. Specifically, WFT view their capacity to manage funds appropriately, analyse the socioeconomic, contextual and cultural issues in-country and within a complex network of players to be important to their success. Critically, WFT acknowledge that it would have been difficult to do so from afar in Aberdeen. WFT has employed an individual with a background in international development and consulting to establish and manage its operations in Africa; who is widely regarded as an expert in market-based solutions for poverty reduction and previously worked in international development and on projects with the World Bank in the areas of market development, emerging markets and the value chain approach. In keeping with the ethos of WFT, WFT Africa has a small team of highly knowledgeable and technical people in place who work across the country offices in Tanzania and Rwanda. The WFT Africa team manage small operational in-country budgets and work with industry contacts to identify areas they can assist and engage in. WFT Africa also uses high level technical advisers, who are kept on a retainer to plug the gaps in technical knowledge in the WFT Africa team. Partnership with GCF The partnership formed with GCF is hugely important to the approach adopted by WFT in Africa. GCF has worked in Africa for almost thirty years and for almost half of that time has been directly involved in supporting agriculture and research in plant science; and small business development and microfinance through a number of local independent organisations that bear the Gatsby name (Kenya Gatsby Trust, Tanzania Gatsby Trust, Uganda Gatsby Trust and Gatsby Cameroon) 3. “We have worked in Africa since 1985, with the overall objective of creating jobs and improving incomes for the poor. We are now focusing on achieving this through a small number of ambitious sector development programmes across East Africa” (Excerpt taken from GCF website, http://www.gatsby.org.uk/en/Africa.aspx).. Each independent institution has its own portfolio of projects in their local environment; they are supported by grants from GCF. GCF has also helped each Institution to think through their strategy, effectiveness, impact, scale and focus. The length of time that GCF has been involved in Africa is well established and means that GCF is already embedded in valuable networks in Africa. “Historically, we have a very deep rooted network in Africa given the local institutions that we have started and the local staff who work in those institutions… and so we do have very embedded networks and a history of funding which provide us with a foundation for our current work” (Head of Africa Operations for GCF). The partnership between GCF and WFT arose from the established work of GCF in the African sector development and a like-mindedness of how systemic change can be instigated in the region. GCF are interested in the transition and catalyst of entire sectors, which meet three main criteria: the sector is considered to be competitive and economically viable, it impacts on large numbers of people, and 3 http://www.gatsby.org.uk/en/Africa.aspx 8 where change is deemed to be made possible (relative to in-country politics, government, momentum, private sector). Thus the similarity in ethos with WFT is observable. The individual who leads the African operations for GCF has a consultancy background in the development industry and has previously worked with the Department for International Development (DFID) and is widely regarded in the development community to be an expert in making markets work for the poor and value chains. WFT and GCF co-fund the programmes in Tanzania and Rwanda and make key decisions together in relation to expenditure, and the setting of a future work plan. WFT and GCF have a steering board whereby they come together to discuss new ideas, they agree and disagree and find ways to move forward together. Moreover, twice a year both organisations come together to engage in a week long strategic overview of the programme and to map out a work plan for the following six month period. WFT take the lead in the operational implementation of both the Chai and Imbarutso programmes. Sector Selection and Value Chain Analysis The process of selecting which sector to focus upon in Africa has been approached by WFT and GCF in a systematic manner. WTF and GCF have conducted research and analysis of multiple sectors in Tanzania to identify: which sectors contribute to the development of economies, which sectors employ significant numbers of people; whether it be as a small holder or micro and small enterprises. The analysis considered which sectors held a comparative advantage in-country and where and how comparative advantage can be changed into a competitive advantage. A range of criteria informed the analysis which included: the potential impact of outreach; the contribution of a sector to foreign exchange, whether existing sectors can be built upon, what policy constraints, if any, exist and importantly determining what level of existing donor intervention already exists in a sector. The presence of too many donors in any one area is not viewed positively, as it can impact negatively on the absorptive capacity of any one sector to use money properly. “One of the biggest problems in development is, at one level, there are too many donors competing for space in inappropriate ways. If you have a foundation that comes in with, for example, $50 million to develop coffee in one country, I wouldn’t even look at it.... I would question the absorptive capacity of that sector to undertake and use money appropriately. I think it will result in market distortions and the last thing you want to do is to compete for space” (Head of African operations for WFT) The sector analysis stage required WFT to meet with representatives from processors, exporters, transporters, farmers, government and the research institutes to discuss with them their problems. Such face to face meetings enabled WFT to build relationships with key stakeholders in the sector, develop a contextual understanding of the challenges and bottlenecks that the sector faces and identify opportunities where value can be added. The tea, cotton and tourist sectors were all considered, but as GCF were already active within the cotton sector the decision was made to discount it. Tourism was also discounted and a decision was reached to focus on the tea sector; primarily because WFT believe it can add value to the sector and not be inhibited by policy constraints. Table 1 outlines the challenges identified by WFT in the TanzanianTea Sector, which it seeks to address through the activities of Chai. Table 1 Here. Building on the key relationships that WFT has developed with key stakeholders in the tea sector a memorandum of understanding (MOU) was subsequently established with the main players including: the Tanzanian Government, Tea Board of Tanzania, the private sector, representatives of small holders and the Tea Research Institute. The MOU sets out how WFT along with GCF can support the industry to develop and grow, and tackle the issues that act to constrain the sector overall. Building on the MOU an in-country advisory committee has been established with the main partners, which supports industry partnership and the sharing of mutually beneficial knowledge. Chai Programme Implementation There are a number of activities being implemented within the Chai programme. First, there is an innovation fund which operates on a matched funding principle as a mechanism to engage with the private sector. The fund operates on a 50/50 cost share basis on commercially viable projects, which have a clear and measurable impact on the smallholder farmer. WFT seek to fund activities that encourage the private sector to try new things, and which they view as both innovative and supportive of the industry. One key area, which WTF is keen to support, is the strengthening of farmer/ factory relations. To illustrate the type of project the fund supports it is useful to explore the example of the Wakoma Tea Factory. Chai has assisted the Wakoma Tea factory to provide extension services to the smallholder farmers in collaboration with the Tea Research Institute of Tanzania (TRI), whereby TRI place extension officers in the field to provide agronomic and production logistic services to the farmers. The farmers are advised on how best to grow their crops and the extension officers coordinate, grade and transport the tea, as well as, organise the payment back to the farmer. This service is commercial and performance based. The service is provided on credit to the factory by the TR, and made possible through the Chai programme. The factory also want to encourage and help farmers to switch from older seedling tea to higher yielding tea, which will help the farmers to increase their crop yield but also increase the throughput of the factory. Chai is helping to put nurseries in place managed in a partnership with the farmers to facilitate the seed change. Within this particular factory, there is also an issue of lack of human capital to pluck the tea, which needs to be, carried out three to four times a month, otherwise the yield and the quality of the tea is affected. Chai is assisting farmers to mechanise the harvesting of their crops so that tea can be plucked on a more regular basis, increasing the volume of their crop and increasing the throughput of the factory. Another example of the work implemented through the Chai programme relates to helping farmers gain title rights to land, which they work. WFT in partnership with the factory are paying to hire land surveyors to help map the land for the farmers and, in turn, help them to register the land in their name. The aim is to encourage farmers to plant tea and be assured that they own the land. Another innovative example of how Chai is impacting positively on the tea sector, relates to its work in relation to the payment of farmers. Previously factories have paid farmers through farmer associations, which are often inefficient and can mean there is a delay in farmers receiving payment. Chai is supporting a direct payment system, whereby once the farmer brings the leaf to the collection site, it is weighed electronically, recorded, the farmer receives a receipt and the information is fed directly to the factory. Relative to this, WFT is now exploring how the success of the MPESA model in Kenya can be replicated in Tanzania. MPESA is a service that enables farmers to be paid through their mobile phones. Farmers with an MPESA account can send and receive payment through their mobile phone and withdraw money from certified world kiosks. As an approach MPESA has revolutionised the payment of farmers in rural Kenya. One further example of the work implemented under Chai is the work undertaken in the price mechanism of green leaf. Historically, farmers in Tanzania have earned around 25% of the price of tea at market, with such a low margin and low return there is less incentive for farmers to invest in crops. Chai, in collaboration with the Tanzanian Tea Board, recognise the inequality and frustrations this causes and have subsequently contracted experts to explore best practice elsewhere. The experts have come up with a market based payment mechanism, which assures that farmers get a base payment for their green leaf when they deliver it. The payment is based on a percentage of the average tea price achieved in the Mombasa auction. Moreover, it is coupled with a bonus payment every six months based upon the performance of each factory. This system ties the farmer to factories and the performance of the factory; it provides incentives to the farmers to provide quality leaf because it improves the money they receive. Importantly, it also encourages farmers to think about market fluctuations, whether it is good or bad, as prices can go up and down. Subsequent 10 systems are being put in place to monitor the effectiveness of the payment system and to capture the data. The aim is to break the cycle of low payments and low yields by putting a system in place that is sustainable and more equitable. Tanzania Interim Results Chai is now nearing the half way point of the original six year timeline and there have been some interesting results already, outlined in table 2. Table 2 here. Chai has positively impacted on the smallholder share of the price of tea at market, which in turn impacts on household wealth and the opportunity for farmers to invest in their crops. The 22% increase achieved in smallholder yield per hectare is impressive and has a positive knock on effect for the throughput of the factories as well as benefiting the smallholder farmer. However, perhaps the most impressive result within the work of Chai so far is the 70% increase in smallholder profits per hectare within a three year period. It is indicative that small interventions, focused on specific geographies can have substantial impact. Following the positive interim results of the Chai programme in Tanzania, WFT in collaboration with GCF have developed a second ‘making markets work programme’ in the tea sector in Rwanda, Imbarutso, which began in 2011. It is therefore useful to explore the implementation of Imbarutso next. Imbarutso Programme Implementation Imbarutso is a newer programme and as such an action plan was developed during the first half of 2011/12, which set out how they could work with government, private factories and small holder groups to increase the efficiency of the tea sector. At the same time, an opportunity arose to facilitate a deal that enabled smallholder farmers to own factories that were in the process of being privatised in Rwanda. Following the lead of the Kenyans, where 600,000 smallholder farmers own 66 factories, and conduct US$650 million of business a year; and are governed by a factory board of elected members but managed by a third party professional management company, The Kenyan Tea Development Agency (KTDA), hired by the farmers. WFT and GCF set about brokering a deal along the similar lines to the farmer owned factories in Kenya. “Where we can come in as a donor, is bring parties to the table, broker an honest discussion between them, educate the government on why this is an important activity and then, another example is we can provide finance” (Head of Africa operations WFT). The deal, was successfully brokered, facilitated the purchase of two factories, Mulindi and Shagasha, in partnership with WFT, GCF and smallholder farmers in Rwanda. The upfront finance for the deal was provided by WFT and GCF and allowed for the successful purchase of the government shares (55% in Mulindi and 60% in Shagasha). The management company that is active in the farmer owned Kenyan factories, KDTA, has been hired to manage the two factories on a short term basis, with the sole intention to support and train up the Rwandans to takeover future management of the factories. The annual free cash flow is distributed to the farmers as an additional payment for the Greenleaf tea. WFT and GCF also receive payment to recover the cost of their investment. After a period of seven years, WFT and GCF will transfer their shares at no cost to the farmer shareholders, or earlier if certain key performance indicators are achieved in business development and the governance performance. Similar to the Company limited by guarantee- WFT Africa, In Rwanda WFT and GCF have developed Rwandan Tea Investment a Scottish based charitable company jointly owned by WFT and GCF, which has invested US$12 million including working capital for both of the factories in Rwanda. “We are a non-profit, we are registered as a non-profit company so if we get our money back from the initial deal and the deal works then that would be fantastic, but the signals have to maintain commercial business “(Head of Africa Operations, WFT). The investment and business is still at a young age, thus there is limited information available on how it has progressed but the successful brokering and completion of the deal itself signals an innovative philanthropic intervention which has real potential to make significant impact on the feasibility of smallholder farming in Rwanda. Discussion The WFT, in partnership with GCF, is engaging in socially and economically innovative philanthropic projects, which seek to restore socio-economic equilibrium in a complex environment, it is captured succinctly by Sir Ian in his introduction to WFT4. “As Wood Group has globalised, I have been increasingly aware of the huge imbalance between the “haves” and “have not’s” across the world. As well as more open trade, globalisation must also mean acceptance of responsibility to help improve the economic wellbeing of those people and nations which have not prospered. Therefore, WFT’s main investment focus will be to help Make Markets Work for the Poor in Sub Sahara Africa with the ultimate goal of creating sustainable economic activity and jobs. We are under no illusion of the complex nature of this challenge.” (Sir Ian Wood, Philanthropist). Sir Ian’s words resonate with the most recent work of Acs (2013), who argues that entrepreneurship; more specifically wealth creation, and philanthropy are inextricably linked. Acs (2013) posits that philanthropy has given an edge to capitalism by promoting fundamental forces, which are necessary to advance technological, social and economic equality. Building on the work of Acs (2013), the importance of embeddedness and the socio-cultural context in which social innovation and economic development occur (Austin et al, 2006; Granovetter, 1985; Ram et al, 2008; Smith and Stevens, 2010; Tapsell and Woods, 2010; Maclean et al., 2013) is exemplified in this single case study. The cultural capital of the entrepreneurial philanthropist, which has contributed to the amassing of considerable personal wealth transfers from wealth creation to philanthropy. The promotion and strengthening of private enterprise as a route to self help, is central to how entrepreneurial philanthropy is practiced. The cautious approach of WFT in relation to the local community and the contextual factors which shape the complex situation is re-assuring from an investment perspective. There is an acceptance of the need to understand the targeted country of philanthropy, its peculiarities, challenges, strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and culture. WFT in collaboration with GCF actively operate at all levels of society, top down and bottom up, this is made possible because of the symbolic capital of the two philanthropists, Sir Ian Wood and Lord Sainsbury and the historical presence of GCF in Africa. It is further strengthened through the engaged approach and in-country presence, which facilitates and maintains access to networks that would undoubtedly be inherently difficult to access from a distance. Sector and value chain analysis are not the sole regard of entrepreneurial philanthropy, but the mix and application of capital wealth in its broadest form is (Gordon, 2011; Harvey et al., 2011; Shaw et al., 2012; Maclean et al., 2013). There are other players in international development who have an interest in sector and value chains, like DFID and the World Bank, but despite the substantial amount of funding which has been pumped into Africa over the last fifty years, it has largely remained unchanged (Brainard and LaFleur, 2008; Kharas, 2008). Furthermore, the plight of the smallholder has remained static. Thus the question arises, why? What can entrepreneurial philanthropists add that other forms of direct foreign investment cannot? This case study shines light on the flexibility and dynamic approach adopted by WFT and GCF in their endeavours to bring sustainable change to the 4 Excerpt taken from WFT website: http://www.woodfamilytrust.org/about-the-trust/meet-the-trustees.php 12 tea sector in Tanzania and Rwanda. Both Heads of African operations at WFT and GCF comment that there is a distinct difference, in their experience, of working for an individual philanthropist who has a wealth of entrepreneurial experience which influences their approach to philanthropy. In particular, flexibility and capacity to respond to challenges, access to elite networks, and on-theground presence and freedom from bureaucracy and from pressure to spend money were cited by both individuals as distinctive factors within this case study. Thus, suggesting that the sites and space of socially innovative philanthropic ventures may be important to their success (Granovetter, 1985; Steyaert and Katz, 2004; Maclean et al., 2013). Furthermore, the command of localised domain and context specific knowledge demonstrated within the case study is indicative that knowledge and understanding of local context and community are important, to the social and economic renewal of fragile environments (Marshall, 2011; Maclean et al., 2013). The policy implications of this form of philanthropy are twofold. First the interim results of the Tanzanian example show how multiple agencies can work in partnership in a top down and bottom up approach to affect change which benefits the small holder. Secondly, the Rwandan example shows how applying business acumen and experience in identifying opportunities to place the command of production in the hands of the small holder farmer can be realised through government and private investors working collaboratively for the benefit of less powerful communities. It is suggestive that policy at a national and international level needs to become focussed on strengthening the position of smallholders within the economic spectrum to progress programmes of poverty reduction. Conclusion The case analysis has sought to provide rich and descriptive and meaningful insights in the working practice of entrepreneurial philanthropy in an international context, as a mechanism to develop understanding and to inform future thinking of how such philanthropy can be supported in developing countries. It is therefore limited in that it is a singular case. In addition, the research for this paper was carried out at the Wood Family Trust based in North-East Scotland. While this is arguably a limitation, in that the researcher was unable to travel to Africa to examine proceedings at first hand, our analysis arguably gains in objectivity and understanding of strategic direction what it might have lost in being closer to the action. Entrepreneurial philanthropy is distinctive from other large-scale charitable giving in three crucial aspects. First, it does not respond to requests for support for causes supported by others. Entrepreneurial philanthropy is distinguished by identifying pressing needs and devising innovative solutions to meet those needs. Second, it is not concerned with reliving the symptoms of social problems but is focussed on addressing root causes and creating and catalysing systemic change and in this particular case study adding value through the strengthening of value chains in the agriculture sector. The overarching theme is to provide sustainable solutions that embrace private enterprise and support wealth creation, job creation and business development (Gordon, 2011). This fits with the overriding philosophy of entrepreneurial philanthropy, that wealth creation is a mechanism that can lift people out of poverty and facilitate the practice of self-help. Third, money is not the most important capital resource in how entrepreneurial philanthropy is practiced. In fact, as is evidenced in this case the financial sum invested is not vast when compared with the personal wealth of the philanthropist, rather a minimalist approach to financial expenditure has been adopted, the smallest amount of money is invested to trigger and catalyse a change in behaviour or a desired response (in industry) to be more competitive. Therefore the totality of resources available to wealthy individuals, who engage in entrepreneurial philanthropy; and how these are used, distinguishes them from other forms of international development aid which typically have big budgets, a finite time scale and a pressure to spend. The flexibility, dynamic and minimalist approach adopted in this particular case is indicative of the findings in the wider study of entrepreneurial philanthropy. WFT in conjunction with GCF have adopted an ambitious but cautious approach in their work in Tanzania and Rwanda, that is slow burning but beginning to come to fruition. The tea sector in these countries is beginning to show vital signs of change, which shows real promise. The Chai and Imbarutso programmes therefore provide a blueprint for other stakeholders with the desire to improve the production and efficiency of the agricultural sector in regions which drastically need support to change. References Acs, Z. (2013). How the wealthy give and what it means to our economic well-being. Princeton University Press. Austin J, Stevenson H and Wei-Skillern J (2006) Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different or both? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 30(1): 1-22. Anheier, H.K., & Leat, D. (2006). Creative philanthropy. New York Routledge. Best, R; Ferris, S and Schiavone, A. (2005) ‘Building linkages and enhancing trust between smallscale rural producers, buyers in growing markets and suppliers of critical inputs’. In, Beyond agriculture- making markets work for the poor: Proceedings of an international seminar. 28 February1 March, 2005, Westminster, London. Bishop, M. & Green, M. (2008). Philanthrocapitalism. London: Black. Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241-258). New York, NY: Greenwood Press. Brainard, L., & LaFleur, V. (2008). Making poverty history? How activists, philanthropists, and the public are changing global development. In L. Brainard & D. Chollet (Eds.), Global development 2.0: Can philanthropists, the public and the poor make poverty history? (pp. 9-41). Washington, DC: Brookings Institute Chell E, Nicolopoulou K and Özkan-Karatas M (2010) Social entrepreneurship and enterprise: International and innovations perspectives. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development. 22 (6), 485-493 De Lorenzo, M., & Shah, A. (2007). Entrepreneurial philanthropy in the developing world: A new face for America, a challenge to foreign aid. Research Paper of American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy (3, December), Washington. Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532-550. Eisenhardt, K.M, & Graebner, M.E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25-32. Gereffi, G; Humphrey, J; Kaplinsky, R amnd Sturgeon, T (2001) Introduction: Globalisation, Value Chains and Development. IDS Bulletin Vol 32 No. 3. Gordon, J. (2011). Power, wealth and entrepreneurial philanthropy in the new global economy. Doctoral Thesis awarded in fulfilment of Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Strathclyde. Gordon, J, Harvey, C, Shaw, E and Maclean, M (forthcoming) ‘Entrepreneurial Philanthropy’ in Harrow, J, Phillips, S and Jung, T (eds) Companion to Philanthropy, Routledge, London Granovetter, M. (1983). The strength of weak ties: a network theory revisited. Sociological Theory, 1, 201-233. Greenwood R and Hinings CR (1993) Understanding strategic change: The contribution of archetypes. Academy of Management Journal 36: 1052-1081 14 Handy, C.B., & Handy, E. (2006). The new philanthropists: The new generosity. London: William Heinemann. Harvey, C, Maclean, M, Gordon, J, Shaw, E. (2011). Andrew Carnegie and the foundations of contemporary entrepreneurial philanthropy. Business History, Vol. 53, No. 3, 424-448.. Jayne, T.S; Yamano,T; Weber,T; Tschirley,D; Benfica,R; Chapoto,A; Zulu,B (2003). Smallholder income and land distribution in Africa: implications for poverty reduction strategies. Food Policy, Vol. 28, Issue 3. Kharas, H. (2008). The new reality of aid. In L. Brainard & D. Chollet (Eds.), Global development 2.0: Can philanthropists, the public and the poor make poverty history? (pp. 53-73). Washington, DC: Brookings Institute. Maclean, M; Harvey, C, Gordon, J. (2013). Social Innovation, Social Entrepreneurship and the Practice of Contemporary Entrepreneurial Philanthropy. International Small Business Journal, forthcoming. Marshall RS (2011) Conceptualizing the international for-profit social entrepreneur. Journal of Business Ethics 98: 183-198. Minot, M and Vargas Hill, R (2007) Developing and connecting markets for the poor. IFPRI 2020 Vision Focus Brief on the World's Poor and Hungry People - October 2007 Peredo AM and Chrisman JJ (2006) Toward a theory of community-based enterprise. Academy of Management Review. 31 (2): 309-328 Perren, L. and Ram, M. (2004) ‘Case Study Method in Small Business and Entrepreneurship Research’, International Small Business Journal, 22 (1). Perrini F, Vurro C and Constanzo LA (2010) A process-based view of social entrepreneurship: From opportunity identification to scaling-up social change in the case of San Patrignano. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development22(6): 515-534. Ponte, S and Gibbon, P (2005) Quality standards, conventions and the governance of value chains. Economy and Society, 34 (1): 1-31. Porter, M. (1985) Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. Free Press: New York). Ram M, Theodorakopoulos N and Jones T (2008) Forms of capital, mixed embeddedness and Somali enterprise. Work, Employment and Society 22(3): 427-446. Schervish, P.G. (1997). Inclination, obligation and association: What we know and what we need to learn about donor motivation. In D.F. Burlinghame (Ed.), Critical Issues in Fundraising (pp. 67-71). New York: Wiley. Shaw, E; Gordon, J; Harvey, C; Maclean, M. (2013). Exploring contemporary entrepreneurial philanthropy. International Small Business Journal, 31(5): 580-599. Siggelkow N (2007) Persuasion with case studies. Academy of Management Journal 50(1): 20-24. Smith BR and Stevens CE (2010) Different types of social entrepreneurship: The role of geography on the measurement and scaling of social value. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 22(6): 575-598. Steyaert C and Katz J (2004) Reclaiming the space of entrepreneurship on society: Geographical, discursive and social dimensions. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 16: 179196. Tapsell P and Woods C (2010) Social entrepreneurship and innovation: Self organization in an indigenous context. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 22(6): 535-556. The Gatsby Charitable Foundation, Impact investment. Understanding financial and social impact of investments in East African agricultural businesses. The Wood Family Trust, Chairman’s Review, 2012. The Wood Family Trust, Trustees Annual Report and Accounts, 2008; 2009; 2010; 2011; 2012. Wennekers, S and Thurik, R. 1999. Linking Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth. Small Business Economics, Vol. 13, Issue 1. World Development Report, 2005, World Bank. Yin, R.K. (2009). Case Research Study. 4th edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Table 1: Factors acting to constrain the growth of the Tanzanian Tea Sector 1. Low smallholder productivity (900kg of made tea per hectare of land in Tanzania, compared with 2,000kg in Kenya) 2. Limited access to inputs such as fertiliser, and ineffective extension services 3. Lack of business experience of farmers 4. Low green leaf price and poor margins for farmers ( smallholders achieve 26% of the made tea price) 5. Poor rural road and green tea leaf infrastructure 6. Low quality of made tea and poor reputation on the world markets 7. Lack of smallholder ability to represent their commercial interests in the processing factories (*adapted from WFT Chairman’s Review Document, 2012) Table 2: Interim results of Chai Programme at end of year 3. 1. Average smallholder share of tea price has risen from 26% to 34% 2. Smallholder yield has increased from an average 950kg per hectare to 1,100kg per hectare, which represents an increase of 22%. 3. Average smallholder profit per hectare has increased by 70% from US$126 per hectare in 2009, to US$218 per hectare in 2011/12. The average tea farmer in Tanzania only has 0.4 hectare of tea. 4. Through the 3 matched grants with the private sector processing factories commercially sustainable services have been provided to 21,000 smallholder farmers. 5. In collaboration with the Tanzanian Tea Board a new pricing mechanism has been introduced that benefits all 30,000 tea farmers in Tanzania. 6. Working with the smallholder tea farmer association the management and efficiency of the 16 representation body of 15,000 tea farmers has been improved. 7. In collaboration with the Tanzania Smallholder Tea Development Agency a pilot land titling project has been launched in a district of Tanzania, if successful it will be rolled out nationally. (* adapted from the WFT Chairman’s Review Document, 2012)