Disputing Irony: A Systematic Look at Litigation About Mediation

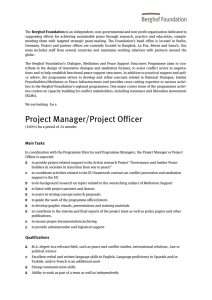

advertisement