Managerial Accounting

advertisement

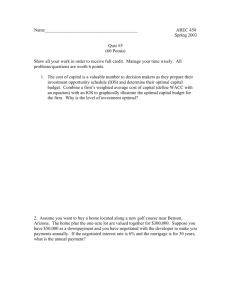

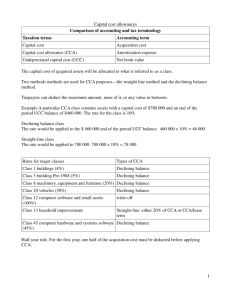

Managerial Accounting Tenth Canadian Edition Connect What You Really Need To Know Chapter 13: Capital Budgeting Decisions A. Capital budgeting is the process of planning significant investments in projects that have long-term implications such as the purchase of new equipment or the introduction of a new product. 1. Capital budgeting usually involves investment; i.e., committing funds now so as to obtain cash inflows in the future. 2. Capital budgeting decisions fall into two broad categories: a. Screening decisions: Potential projects are categorized as acceptable or unacceptable. b. Preference decisions: After screening out all of the unacceptable projects, more projects may remain than can be funded. Consequently, projects must be ranked in order of preference. 3. The time value of money is a central consideration in capital budgeting. A dollar in the future is worth less than a dollar today for the simple reason that a dollar today can be invested to yield more than a dollar in the future. a. Discounted cash flow methods give full recognition to the time value of money. b. Two of the methods presented in the chapter discount cash flows—the net present value method and the internal rate of return method. B. The net present value method is illustrated in Exhibit 13-1, Exhibit 13-2, Exhibit 13-3, and Exhibit 13-4. The basic steps in this method are: 1. Determine the required investment. 2. Determine the future cash inflows and outflows that result from the investment. 3. Use the present value formulas (or tables) in Appendix 13A to find the appropriate present value factors. a. The values (or factors) in the present value tables depend on the discount rate and the number of periods. b. The discount rate in present value analysis is the company’s required rate of return, which is often the company’s cost of capital. The cost of capital is the average rate of return the company must pay its long- term creditors and shareholders for the use of their funds. The details of the cost of capital are covered in finance courses. 4. Multiply each cash flow by the appropriate present value factor and then sum the results. The end result (which is net of the initial investment) is called the net present value of the project. 5. In a screening decision, the investment is acceptable if the net present value is positive. If the net present value is negative, the investment should be rejected. C. Discounted cash flow analysis is based on cash flows—not accounting net operating income. 1. Typical cash flows associated with an investment are: a. Outflows include initial investment, installation costs, increased working capital needs, repairs and maintenance, and incremental operating costs. b. Inflows include incremental revenues, reductions in costs, salvage value, and release of working capital at the end of the project. 2. Depreciation is not a cash flow and therefore is not included in net present value calculations. (However, depreciation can affect taxes, which is a cash flow. This aspect of depreciation is covered in the section “Appendix 13B: Income Taxes in Capital Budgeting Decisions”.) 3. Projects frequently require an infusion of cash (i.e., working capital) to finance inventories, receivables, and other working capital items. Typically, at the end of the project this working capital can be recovered. Thus, working capital is counted as a cash outflow at the beginning of a project and as a cash inflow at the end of the project. 4. We usually assume that all cash flows, other than the initial investment, occur at the end of a period. D. The total-cost or the incremental-cost approach can be used in conjunction with the net present value method to compare projects. 1. The total-cost approach is the most flexible and the most widely used method. Exhibit 13-5 illustrates the total cost approach. Note in Exhibit 13-5 that all cash inflows and all cash outflows for each alternative are included in the solution. 2. The incremental-cost approach is a simpler and more direct route to a decision since it ignores all cash flows that are the same under both alternatives. The incremental-cost approach focuses on differential costs. Exhibit 13-6 illustrates this approach. 3. If done correctly, both the total-cost and incremental-cost approaches will lead to the same decision. E. Sometimes no revenue or cash inflow is directly involved in a decision. In this situation, the alternative with the least cost should be selected. The least cost alternative can be determined using either the total-cost approach or the incremental approach. Exhibits 13-7 and 13-8 illustrate least-cost decisions. F. It is often difficult to quantify all the costs and benefits involved in a decision. An investment in automation provides a good example. 1. The reduction in direct labour cost from automation may be easy to quantify. Intangible benefits, such as greater throughput or greater flexibility in operations, are usually very difficult to quantify. It would be a mistake to ignore these intangible benefits simply because they are difficult to quantify. 2. The difficulty can often be resolved by computing how large the intangible benefits would have to be to make the investment attractive. The steps in this approach are: a. Compute the net present value of the tangible costs and benefits. If the result is positive, the investment is acceptable because the intangible benefits simply make it even more attractive. b. If the net present value of the tangible costs and benefits is negative, compute the additional net annual cash inflows that would make the net present value positive. c. If the intangible benefits are likely to be at least as large as the required additional net annual cash inflows computed in (b), accept the project. G. The internal rate of return method is another discounted cash flow method used in capital budgeting decisions. 1. The internal rate of return is the rate of return promised by an investment project over its useful life; it is the discount rate for which the net present value of the project is zero. 2. When the cash flows are the same every year, the following formula can be used to find the internal rate of return: Factor of the internal rate of return = Investment required Net annual cash inflows 3. For example, assume an investment of $3,791 is made in a project that will last five years and has no salvage value. Also assume that the annual cash inflow from the project will be $1,000. Factor of the internal rate of return = $3,791 $1,000 = 3.791 The same cash inflow is received at the end of every year beginning with the first year, so use a present value table which contains the present value factors for annuities, or alternatively, use the IRR formula in Microsoft Excel. Because this is a project with a five-year life, use the 5-year row in the table. Scanning along the 5-year row, it can be seen that this factor represents a 10% rate of return. Therefore, the internal rate of return is 10%. 4. If the cash inflows are not the same every year, the internal rate of return is found using trial and error or a software application. The internal rate of return is whatever discount rate makes the net present value of the project equal zero. 5. In a screening decision, the internal rate of return is compared to the required rate of return. If the internal rate of return is less than the required rate of return, the project is rejected. If it is greater than or equal to the required rate of return, the project is accepted. H. Some projects have cash flows that are difficult to estimate. Intangible benefits that may result from upgrading production equipment such as improved quality or reliability can be difficult to quantify with any degree of certainty. However, management can cope with this uncertainty by estimating the dollar amount of intangible benefits that would be required to make a project attractive. If management believes the value of the intangible benefits will meet or exceed the required amount, the project should proceed. I. Preference decisions come after screening decisions and involve ranking investment projects. Such a ranking is necessary whenever there are limited funds available for investment. 1. Preference decisions are sometimes called ranking decisions or rationing decisions because they ration limited investment funds among competing investment opportunities. 2. When using the internal rate of return to rank competing investment projects, the preference rule is: The higher the internal rate of return, the more desirable the project. 3. If the net present value method is used to rank competing investment projects, the net present value of one project should not be compared directly to the net present value of another project, unless the investments in the projects are of equal size. a. To make a valid comparison across projects that require different investment amounts, a profitability index is computed. The formula for the profitability index is: Profitability index = Present value of cash inflows Investment required The profitability index is an application of the idea of contribution margin per unit of a constrained resource from Chapter 12. In this case, the scarce resource is the investment funds. b. The preference rule when using the profitability index is: The higher the profitability index, the more desirable the project. J. The present value method is generally superior to the internal rate of return method, although both are used in practice. The internal rate of return method assumes that any cash flows received during the life of the project can be reinvested at rate of return equal to the internal rate of return. This assumption is questionable if the internal rate of return is high. In contrast, the net present value method assumes that any cash flows received during the life of the project are reinvested at a rate of return equal to the discount rate. Ordinarily, this is a more realistic assumption. K. Post-audit appraisals of investment projects involve a post-approval review to evaluate whether the estimated benefits (incremental revenues, cost savings, etc.) have been realized. The post-appraisal review can reveal any tendencies managers may have had to overstate benefits or understate additional costs when seeking original approval. The key in post-appraisal analysis is to use actual data. L. Two capital budgeting methods are considered in the chapter that do not involve discounting cash flows. One of these is the payback method. 1. The payback period is the number of years required for an investment project to recover its cost out of the cash receipts it generates. a. When the cash inflows from the project are the same every year, the following formula can be used to compute the payback period: Payback period = Investment required Net annual cash inflows b. If new equipment is replacing old equipment, the “investment required” should be reduced by any salvage value obtained from the disposal of old equipment. And in this case, in computing the “net annual cash inflows,” only the incremental cash inflow provided by the new equipment over the old equipment should be used. 2. The payback period is not a measure of profitability. Rather it is a measure of how long it takes for a project to recover its investment cost. 3. The payback method ignores the time value of money and all cash flows that occur once the initial cost has been recovered. Therefore, this method is very crude and should be used only with a great deal of caution. Nevertheless, the payback method can be useful in industries where project lives are very short and uncertain. M. The simple rate of return method is another capital budgeting method that does not involve discounted cash flows. 1. The simple rate of return method focuses on accounting net operating income rather than on cash flows: Simple rate of return = Annual Annual incremental _ incremental revenue expenses Initial investment If new equipment is replacing old equipment, then the “initial investment” in the new equipment is the cost of the new equipment reduced by any salvage value obtained from the old equipment. 2. Like the payback method, the simple rate of return method does not consider the time value of money. Therefore, the rate of return computed by this method is not an accurate guide to the profitability of an investment project. Appendix 13A: The Concept of Present Value A. Since most business investments extend over long periods, it is important to recognize the time value of money in capital budgeting analysis. Essentially, a dollar received today is more valuable than a dollar to be received in the future for the simple reason that a dollar received today can be invested—yielding more than a dollar in the future. B. Present value analysis recognizes the time value of money. 1. Present value analysis involves expressing a future cash flow in terms of present dollars. When a future cash flow is expressed in terms of its present value, the process is called discounting. 2. Use Exhibit 13A formulas, a financial calculator, or Microsoft Excel, to determine the present value of a single sum to be received in the future. This table contains factors for various rates of interest for various periods, which when multiplied by a future sum, will give the sum’s present value. 3. Use Exhibit 13A formulas, a financial calculator, or Microsoft Excel, to determine the present value of an annuity, or stream, of cash flows. This table contains factors that, when multiplied by the stream of cash flows, will give the stream’s present value. Be careful to note that this annuity table is for a very specific type of annuity in which the first payment occurs at the end of the first year. Appendix 13B: Income Taxes in Capital Budgeting Decisions A. Income taxes affect cash flows and therefore should usually be considered in capital budgeting. However, nonprofit entities such as hospitals, schools, or governmental units are not subject to income taxes and may use the simpler approach in Chapter 13 that ignores taxes. B. Both the costs and benefits of a project should be estimated on an after-tax basis. 1. The true cost of a tax-deductible item is the amount of the payment net of any reduction in income taxes due to the payment. An expenditure net of its tax effects is known as an after-tax cost. For example, assume that a company needs to repair a machine at a cost of $6,000. The cost of the repairs is a tax-deductible expense. If the income tax rate is 30%, the after-tax cost of the repairs is: Cost of repairs Reduction in taxes due to the overhaul (30% × $6,000) .................................. After-tax cost $6,000) (1,800) $4,200) 2. The net after-tax cost (cash outflow) for any tax-deductible expenditure can be computed as follows: After-tax cost = (1 – Tax rate ) × Tax deductible cash expense 3. Not all cash outflows are tax deductible expenses. a. An investment in working capital is not tax-deductible; it is not an expense. b. The cost of a depreciable asset is not tax deductible in the period in which it is purchased. However, CCA on the asset is tax deductible. (See section D and E below.) C. As with cash expenditures, taxable cash receipts must be placed on an after-tax basis. 1. A cash receipt net of its tax effect is known as an after-tax benefit. For example, assume that a company receives $100,000 from sale of services. If the tax rate is 30%, the after-tax benefit is: Revenue Income tax payment required (30% × $100,000) .................... After-tax benefit $100,000) (30 000) $ 70,000) 2. The net after-tax cash inflow from revenue or other taxable cash receipts can be computed as follows: After - tax benefits = (1 – Tax rate ) × Taxable cash receipt 3. This formula can be used for a project that does not bring in any additional revenue but saves cost. The cost savings can be treated the same as a cash receipt. The formula can also be applied to net taxable cash receipts, which is the difference between taxable cash receipts and tax-deductible cash expenses. 4. Not all cash receipts are taxable. For example, the release of working capital at the termination of an investment project is not a taxable cash inflow. D. Accounting depreciation is not an allowable expense for tax purposes. Instead, an allowance referred to as capital cost allowance (CCA) is permitted by the Canadian Income Tax Act. CCA is the Tax Act’s counterpart to accounting depreciation. Although CCA involves no outflow of cash directly, because it is fully deductible in arriving at taxable income, it does have an effect on the amount of taxes that a firm pays. Therefore, CCA indirectly has an effect on cash flows. 1. The CCA deduction acts as a shield (or protection) against tax payments. In effect, CCA deductions shield profits from taxation and thereby lower the amount of income taxes that a company has to pay. 2. The formula used to compute the CCA tax shield is: CCA deduction × Tax rate = Tax savings from the CCA tax shield E. The present value of these tax savings from the CCA tax shield is required for the discounted cash flow analysis. 1. For tax purposes, all capital assets are grouped into prescribed asset classes or pools. For each class, a specific maximum CCA rate is prescribed. The size of the rate is influenced by a combination of several factors including social, economic, and political. 2. With few exceptions, the maximum annual CCA deduction is computed by the declining balance method. It is equal to the prescribed CCA rate for the class multiplied by the year-end declining balance of the assets in the class, called the undepreciated capital cost (UCC). 3. Because the CCA deduction is calculated on a declining balance of a pool of assets, and not a single asset, a company is able to claim CCA deductions and thus tax savings from an asset even after the asset has been disposed of. 4. In the year an asset is acquired, only one-half the prescribed rate is permitted for calculating CCA. Thereafter the full rate is used. 5. On the disposal of an asset the lesser of the original cost of the asset and the proceeds is deducted from the pool. F. A comprehensive example of income taxes and capital budgeting is given in Exhibit 13B-3. Carefully review this example including the accompanying explanation of the individual items in the exhibit. 1. Notice that all cash flows involving tax deductible expenses and taxable receipts have been placed on an after-tax basis by multiplying the cash flow in each case by one minus the tax rate. 2. Also notice that the present value of the CCA tax shield has been calculated using the CCA tax shield formula introduced earlier in the chapter in Examples 1 and 2. Recall that the CCA rate is applied on a declining balance basis and therefore the CCA tax shields represent an infinite stream. Thus, calculating the tax shield in any other way is not only impractical but will only give an approximation. a. The first part of the formula, ( Cdt d+k × 1 + 0.5 k 1+k ) represents the present value of all CCA tax shields that would be derived from the asset if it were never disposed of, given that only one-half the normal CCA amount is deductible in the first year. The term, (1 + 0.5k)/(1 + k), is a correction factor for the half-year rule. b. The second part of the formula, ( (dS+dtk) n × (1 + k)-n ) represents the CCA tax shield lost because the disposal of the asset for its salvage value results in a lower CCA deduction for the year of disposal and future years. Again this can be viewed as a correction factor to the term (Cdt)/(d + k), which assumes that the asset is never disposed of. 3. These two above points should be studied with great care until both are thoroughly understood. What To Watch Out For (Hints, Tips and Traps) Consider the following illustration to demonstrate the limitations of the payback method. You are asked to choose between two alternatives that each require an initial investment of $4,000. Option A returns $1,000 at the end of each of four years. Option B returns $4,000 at the end of the fourth year. Under the payback method, Option A and Option B are equally preferable. Note, however, that Option A is really better since the cash flows come earlier. Now add the information that in Year 5, Option A will produce an additional cash inflow of $500,000 but that Option B will never generate another dollar after the fourth year. Reconsider the question of preference of Option A or Option B using only the payback method. The payback method ignores the time value of money and does not measure profitability; it just measures the time required to recapture the original investment and will ignore any cash flows after the original investment has been recaptured (i.e., in this example it will ignore all the cash flows after Year 4 for both Option A and Option B since both have a payback of exactly 4 years, thus, the fact that you will receive an additional $500,000 from Option A in Year 5 is not taken into consideration with the payback method). The role of working capital in capital budgeting often confuses students. The initial investment in working capital at the beginning of the project for items such as inventories is recaptured at the end of the project when the working capital is no longer required. Thus, working capital is recognized as a cash outflow at the beginning of the project and as a cash inflow at the end of the project (a common error is to omit the release the working capital at the end of the project). Any decision always has at least two alternatives. Often one of these alternatives is the status quo. In problems evaluating a single project, the incremental-cost approach is usually used. The incremental costs and benefits of the project relative to the status quo are the focus of the analysis. While studying the effects of income taxes on capital budgeting it is important to remember that not all receipts (cash inflows) or disbursements (cash outflows) are taxable. For instance, for example the working capital needed at the beginning of the project and the eventual release of working capital at the end of the project are cash flows but are not counted as income for financial accounting purposes or income tax reporting purposes. Try to think of other non-taxable cash receipts and non-tax deductible cash disbursements (such as proceeds from loans, issue of share capital, repayment of the principal portion of loans, the sale of fixed assets at book value, etc). Second, recall that when an asset is purchased, a cash outflow occurs. Depreciation (and the CCA tax shield) is just the allocation of that purchase price over some estimated life.