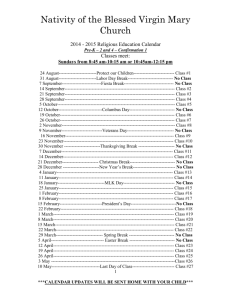

The Calendar of Christ and the Apostles

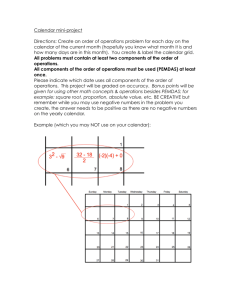

advertisement