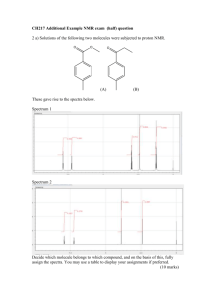

spexp1

advertisement

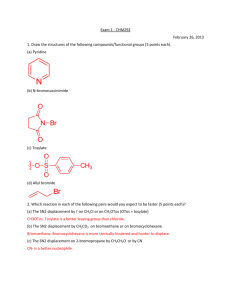

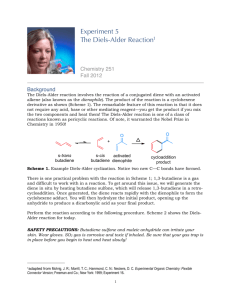

Spring Organic Chemistry Experiment #1 Diels-Alder Reaction Suggested Reading Jones Section 12.12 (pages 587-598) and Section 20.4 (pages 1133-1139) On 2D NMR: Chapters 5 and 10 of Organic Structure Analysis (Topics in Organic Chemistry) by Philip Crews, Jaime Rodriguez and Marcel Jaspers (Wilmot Call # 5 4 7 . 1 2 2 C r e – o ve r s i ze b o o ks ) On X-Ray Crystallography: http://www.stolaf.edu/people/hansonr/mo/x-ray.html http://www.iucr.org/iucr-top/index.html http://www.ruppweb.org/Xray/101index.html Introduction Last semester, you were introduced to the theory and practice of NMR spectroscopy. In this experiment, you will be introduced to some of the more modern and advanced techniques involving NMR that enable chemists to deduce the structure of more complex molecules. In particular, these techniques are especially useful in the structural elucidation of natural products and biological molecules. You should already be familiar with standard one-dimensional (1D) proton and carbon NMR spectroscopy as well as 13C DEPT spectroscopy. In today’s experiment, you will be introduced to three new techniques: (a) two-dimensional (2D) 1H-1H COSY spectroscopy (b); 2D 1 H-13C HETCOR spectroscopy and (c) X-ray crystallography. As you might recall from last semester, DEPT stands for distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer. The DEPT technique has been developed to distinguish among the different types of carbons in a molecule (CH, CH2, CH3). The most familiar DEPT spectrum is the 13C DEPT-135 spectrum. In a DEPT135 spectrum, there are two types of signals (upward pointing and downward pointing). The upward pointing signals arise from either CH or CH3 carbons, whereas the downward pointing signals arise from CH2 groups. A quaternary carbon (one which does not contain a hydrogen) does not show a signal in the DEPT spectrum. An example spectrum is shown below. Note that there are four signals in the fully decoupled 13C spectrum for 2-butanol (one signal for each chemically nonequivalent carbon). In the DEPT spectrum for 2-butanol, there are three upwardly pointing signals, two arising from CH3 groups and one from a CH group. The single downwardly pointing signal (at 32 ppm) arises from the lone CH2 group. It should be apparent that the DEPT technique provides an excellent method for the sorting of 13C signals into methyl, methylene, methine, or quaternary carbons. Pulsed NMR spectroscopy has enabled the chemist to devise experimental methods for the solution of complex organic structures. Traditional one-dimensional techniques do not allow the observer to discern complicate patterns when peak regions overlap. Such a situation normally defies elucidation by the interpreter. However, two-dimensional NMR techniques have arisen to allow for more definitive peak assignments and structural elucidation. A two-dimensional spectrum has two chemical shift axes and a third axis corresponding to peak intensity (a 1D plot has one shift axis and one intensity axis). The resultant spectrum when viewed from the side appears as a “mountain range”. Normally, however, we view the spectrum from the top in a form called a contour plot (see below). These contour plots (when correctly analyzed) show the correlation between neighboring nuclei in the molecule. The most common method involves a 1 H-1H shift correlation; that is, protons that are coupled to one another. This technique is called “correlation spectroscopy” or COSY. An example of a COSY spectrum is shown below. Remember, we view the plot from above (top view). Along the x-axis is a one-dimensional proton NMR of ethyl vinyl ether. Along the y-axis is another one-dimensional proton NMR of ethyl vinyl ether. All of the dots (peaks) that arise inside the box (contour plot) are significant peaks that will yield important structural information. Notice that some peaks lie along a diagonal while others are off of the diagonal. The peaks along the diagonal simply represent the individual peaks one each 1D proton NMR. The important peaks are the ones that are not along the diagonal. These peaks are the cross peaks. The cross peaks arise from pairs of protons that are splitting one another (that is, they are coupled or correlated). How do we use this information? The first thing we need to do is find the peaks along the diagonal and draw a line through them. Then, we can start at any cross peak (let’s use A) and draw a straight line vertically (up) to the diagonal and horizontally (over) to the diagonal. Notice that we have intersected the diagonal at two different peaks (1.1 ppm and 3.8 ppm). The protons giving rise to the peak at 1.1 ppm are from the terminal methyl group (labeled “a”). The protons giving rise to the peak at 3.8 ppm are from the methylene group (labeled “b”). Therefore, we can conclude that the cross peak A results from the correlation (coupling) of the methyl group protons with the neighboring methylene protons (as expected). The other cross peaks can be analyzed in a similar fashion. A second 2D NMR technique that also involves nuclear correlation is HETCOR or heteronuclear correlation spectroscopy. The appearance of a HETCOR spectrum is very similar to the COSY spectrum. Each axis along the perimeter represents a 1D spectrum. However, in HETCOR, one axis contains a 1D proton NMR and the other axis contains a 1D carbon NMR. The resultant HETCOR spectrum, therefore, indicates the coupling between protons and the carbon to which they are attached. For example, a HETCOR spectrum of 2-methyl-3-pentanone is shown below. Notice that a diagonal set of peaks does not exist in the example spectrum. A straight line is drawn from each cross peak to the x and y-axes. Notice in our example that cross peak A arises from the correlation of the carbon peak at 5 ppm on the x-axis and the proton peak at 0.9 ppm on the y-axis. We would conclude that the terminal methyl protons (of type “a”) are located on the carbon at the 5 ppm chemical shift. As far as X-ray crystallography is concerned, I recommend that you read the links provided at the beginning of this experimental summary. I will introduce some techniques in the laboratory for working up raw crystallographic data. Certainly, each of these examples has not demonstrated the full power of two-dimensional techniques for solving structures. However, you would be hard pressed to solve the structure of complex synthetic and biological molecules without employing one or both of these techniques. In fact, you will likely find that these techniques will be very helpful in elucidating the structure of your unknown in today’s experiment. Chemistry In 1927, Otto Diels and Kurt Alder obtained a compound from the reaction of eucalyptus oil with maleic anhydride. Upon crystallization they described the product as forming "grosse glasglanzende Krystalle von ungewohnlicher Schonheit (what’s the German translation here?). Little did they know that their discovery would result in one of the most famous and widely used organic reactions in history. The reaction is useful because of its high yield, production of sixmember rings, carbon-carbon bond forming potential, and stereospecificity. In 1950, they received the Nobel Prize for their work. The Diels-Alder reaction is an example of a cycloaddition reaction between two molecular components: the diene and the dienophile. The diene consists of a molecule containing a conjugated double bond system. The dienophile is typically an alkene. Therefore, a total of 6 pi electrons are involved in the reaction mechanism --- 4 pi electrons from the diene and 2 pi electrons from the dienophile. Thus, the Diels-Alder reaction is a [4+2] cycloaddition reaction. An example is shown below. Some very interesting (and, indeed, groundbreaking chemistry) followed the discovery by Diels and Alder. In the 1960's, Robert Woodward (Harvard), Roald Hoffmann (Cornell), and Kenichi Fukui (Kyoto) each proposed a molecular orbital explanation for the Diels-Alder reaction. The resultant theory is called the "Conservation of Orbital Symmetry" or "Frontier Orbital Theory". Again, the work resulted in all three men receiving the Nobel Prize in chemistry. Objective In today's experiment, you will perform a recapitulation of the classic reaction by Diels and Alder) in which a terpenoid (natural product essential oil) will be used as the diene and maleic anhydride will function as the dienophile. There are many examples of essential oils from natural products (e.g. eucalyptus oil) that contain conjugated diene or triene components. Certainly, eucalyptus oil is not the only example of an essential oil containing a diene or a triene. Other examples include: limonene -- lemony odor in lemons, oranges, and other fruits -myrcene -- fragrance and flavor of bay leaves (also present in hops) -ocimene -- found in Javanese oil of basil -phellandrene -- found in ginger grass, cinnamon, and star anise -phellandrene -- found in lemon oil and peppermint oil -terpinene -- found in the essential oils of cardamom, marjoram, and coriander. As is typical of conjugated dienes from essential oils, they can be readily separated because they have different chemical properties from the other constituents found in the oil. Our objective is to form a Diels-Alder adduct that will separate from the mixture as a crystalline product. You should be able to derive its structure from mp analysis, IR, 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, 13 C-DEPT, 1H-1H COSY, 1H-13C HETCOR, and x-ray crystallography. In fact, you will soon discover that you will need ALL of these techniques to identify the 3-D structure of the DielsAlder adduct (reaction product). Procedure Physical properties addendum: diene oil MW = 136.2 g/mol b.p. = 171-178 °C d = 0.838 g/mL melting points of maleic anhydride adducts of some common natural product dienes: -myrcene 33-34 °C -terpinene 60-61 °C -phellandrene 126-127 °C allo-ocimene 83-84 °C Take a sample vial of one of the diene oils from the hood. Weigh the vial and using 10 mL of anhydrous diethyl ether transfer the oil from the vial to a 25 or 50 mL round-bottom flask. Reweigh the vial and determine the mass of crude diene oil being used in the reaction. Determine the mass and molar amount of diene in your sample of oil based upon the fact that the oil contains 50% of the diene component. Calculate the amount of maleic anhydride required to react with the diene based upon the fact that the diene and dienophile react in a 1:1 equivalency ratio. Determine the theoretical yield of the Diels-Alder reaction based upon the calculated mass of starting diene. Add the maleic anhydride to the flask and gently reflux for 45-60 minutes. While the flask is still warm, transfer the reaction mixture to a small beaker. Cover the beaker with a watch glass and let it cool to room temperature. Once at room temperature, transfer for further cooling to an ice bath. Collect the adduct by vacuum filtration and wash the crystals on the filter paper with 10 mL of COLD petroleum ether. Recrystallize the adduct from dry methanol being sure to avoid prolonged boiling. Dry the adduct and determine its mass, and calculate its % yield. Prepare a 100 mg sample for NMR analysis in the usual fashion using CDCl3/TMS as the NMR solvent. Obtain the following data on your own: Mp IR (thin film) 1 H-NMR 13 C-NMR The following data will be provided for you: 13 C-DEPT H-1H COSY 1 H-13C HETCOR x-ray crystallography (raw) – you will learn how to work up this data set using Mercury. 1