Case Studies on the Participation of Conflict

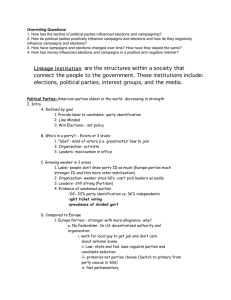

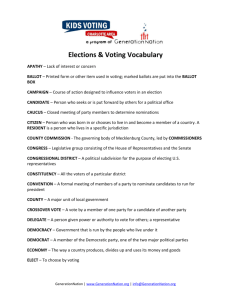

advertisement