section ii- internal ratings based capital requirements

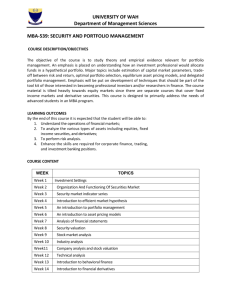

advertisement