Exhibit Design

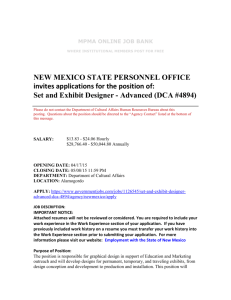

advertisement

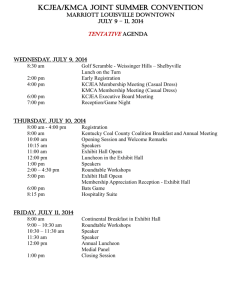

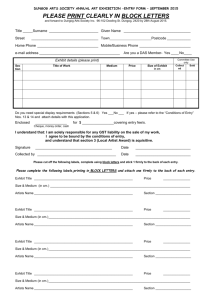

National History Day Creating Exhibits Entries Survival Guide Group Topic: _______________________ Names: _______________________ _______________________ Creating Exhibit Entries Exhibits are designed to display visual and written information on topics in an attractive and understandable manner. They are similar to exhibits found in a museum. People walking by should be attracted to an exhibit's main idea and, therefore, stop to learn more about the topic. To be successful, an exhibit must create an effective balance between visual interest and historical explanation. The most common form of exhibit entry is a three-panel display. This style is the least complicated to design and build but is still a very effective way to present information. Here are some tips for this style: Be sure the title is the main focus of the center panel. Use the center panel to present the main ideas. The side panels are best used either to compare issues about the topic or to explain related detail. Artifacts or other materials may also be placed on the table between the side panels. Labeling The labels used for the title and main ideas are very important because they direct the viewer's eye around the exhibit. One way to make labels stand out is to have the writing on a light-colored piece of paper with a darker background behind it. This can be done with construction paper, tag board, or mat board. Dark black lettering makes labels easier to read. Photographs and written materials also stand out more if they are placed on backgrounds. Exhibit Design Although students will be able to explain their exhibits during the initial judging, a successful exhibit must be able to explain itself. This makes it important to design an exhibit so that the photographs, written materials and illustrations are easy to understand. It is tempting to put as much onto the panel boards as possible, but this usually makes for a cluttered and confusing display. Students should try to select only the most important items for their exhibit boards. Clarity and organization are the most important goals for an exhibit design. "HELP! For National History Day Exhibit Projects" Go to the link below for an exhibit designer's booklet for doing National History Day exhibits produced by the pro's at the Hoover Institution. Cultivate the inner artist or graphic designer! (After the research and interpretation is completed…). http://hoover.archives.gov/education/nhd/index.html Exhibit Design Guidelines Two hand-outs illustrate the importance of design in the creation of a National History Day exhibit. Orientation, Segmentation and Explanation addresses overall exhibit design and Levels of Text demonstrates the importance of titles and font size in clear exhibit design. You may want to look into using fomecore or gatorboard for a more professional looking project. Three-Dimensional Exhibits A three-dimensional exhibit is more complicated to construct but can be an effective presentation style. As in the three-panel display, one side should contain the title and main idea. As viewers move around the exhibit the development of the topic can be explored. It is not necessary for the exhibit itself to be able to spin. It may be set on a table (or on the floor) so that people can walk around it. Word Limit There is a 500-word limit for student-composed written materials on an exhibit. View examples of how to count words and what constitutes student-composed materials: 500 Word Limit For Exhibit Category: The word limit counts toward any student-composed written materials that are used on an exhibit (excluding the title page, process paper and annotated bibliography). For example: A date counts as one word, while each word in a name is individually counted. Therefore, “January 1, 1990” counts as one word, but “John Quincy Adams” counts as three. Words such as “a,” “the,” and “of” are counted as one word each. The limit does not include words found in materials used for illustration, such as documents, artifacts or graphs not created by the students, or to quotations from primary sources such as oral history interviews, letters or diaries. These materials are not student composed. Brief citations crediting the sources of illustrations or quotations included on the exhibits do not count toward the 500-word limit. Words in timelines or scrapbooks do count toward the limit if they are student composed. But, if a timeline is a transcription of a secondary or primary source then it is not student composed and does not count toward the word limit. For more information, check the NHD website explaining exhibits: http://www.nhd.org/Exhibit.htm Elements of an Effective Exhibit Orientation Make sure the title and subtitle of the exhibit are prominent features of the design. Make the main idea or thesis clear to the viewer. Segmentation Organize the exhibit into subtopics. Use design elements to make subtopics clear to viewer. Explanation Use clear and concise captions and text to: 1. Identify pictures, objects, or documents, or 2. Interpret information for the viewer. Levels of Text: Introduction to the use of labels on historical displays A TOWN BUILT ON IRON The main title introduces the topic and attracts viewer interest “The Evolution of Hibbing, Minnesota, 1880 — 1980” The subtitle focuses the topic and limits what the project will interpret Moving the Town A subject label breaks down the topic into smaller parts for explanation and organization. These labels guide the viewer around the display. The original townsite of Hibbing was located over a rich lode of iron ore. Because the ore was more valuable than the town, the buildings of Hibbing were moved to a new site in 1919. Captions are the most detailed label and provide opportunity for interpretation. These should be short, active, and clear. Exhibit Label Basics, Part 3: Content. Bulletin 9 Summer 1999 By Kenneth DeRoux, Curator of Museum Services, Alaska State Museum This is the third part of a 3-part series on making exhibit labels. Part 1 (Bulletin 5) discussed basic guidelines for label design, including kinds of labels, length, size, and placement. Part 2 (Bulletin 7/8) described techniques for making and mounting labels. Here I will discuss some basic considerations for label content. Purpose Labels provide a means for visitors to connect with objects in a museum. They may provide only the most basic identifying information for an object, or they may provide additional levels of interpretation, tying together numerous objects, facts and ideas into a thematic exhibition. (For a discussion of different types of labels, see Bulletin #5). In all cases, labels should be easily visible, readable and enhance the viewing experience. Effective labels go hand-in-hand with clearly conceived ideas about how exhibits are organized and presented. Ideally, they should be an integral part of your exhibit design, rather than added to an exhibit after the fact. Keep it simple. Most museum visitors spend relatively little time on any one exhibit. They tend to keep moving, stopping at what interests them. They will often spend more actual time reading labels than looking at objects, since an object can be "seen" in a few seconds. Even so, the label should serve to reinforce the experience of the object. A strong label will often begin with a concrete reference to the object(s) being discussed, such as "This wall clock stopped at the precise time of the Good Friday Earthquake of 1964." The basic units of information should answer the questions what?, where?, when?, who? how? and why? Ask yourself "What questions will the visitor ask about this material?" and try to answer them. Keep the label directly related to what the viewer is seeing. Don't forget the why? Question. Why is this object in the museum? If there is some story connected to it, your visitors will love to hear it. Reading labels should not be like reading an exhibit catalog. Remember that you are writing for people who are reading standing up and possibly bending forward. Resist the temptation to provide too much additional or extraneous information. Large blocks of text will turn away many viewers. The rule-of -thumb for comfortable label length is between 75 and 150 words. If the label must be longer, make sure it is broken into paragraphs or blocks of text no more than 100 words in length. Sub-headings above each paragraph will give viewers easier access to the material. (This paragraph is 95 words.) Tips Here are some frequently mentioned guidelines for writing effective labels: Use simple sentences. Keep them short but vary the length. Don't use sentences more than 25 words long. Avoid excessive use of commas. Explain unfamiliar words and concepts - you don't want to make your visitor feel uneducated. Write so that an eighth-grader can understand the vocabulary, but provide information that will keep an adult interested. Some word processing programs, such as Microsoft Word®, can check for readability as well as spelling, grammar and passive voice. Use active verbs. Avoid the passive voice, which is excessive use of the verb "to be", (is, are, was, were). In passive voice, the object acts upon the subject, such as "Gold dust was used by miners to pay debts," instead of " Miners paid debts with gold dust." Don't provide more than 6 or 7 key items of information per label. Relate dates or unfamiliar concepts or practices to dates, etc. that the viewer is familiar with. Read the label out loud to insure that the words have an easy flow to them. Always proofread, then proofread again. Advanced tips Use graphics, photographs, maps or other visuals where possible to involve the viewer more directly in making connections. Direct the viewer's attention to specific aspects of the object. Occasionally, and where appropriate, ask the viewer open-ended questions about what he/she is seeing. Offer up puzzles that might be presented by the material. Don't edit out all emotion or controversy from your labels. But when presenting controversial material, try to be unbiased. Strive to be aware of bias (cultural, political, etc.) within your own writing and correct for it if necessary. Develop a style manual for labels for your museum. This helps establish consistency in formatting as well as for grammar, punctuation, and usage. Finally, don't sacrifice clarity for economy. Editing labels down to reduced lengths can sometimes produce unintended inferences. It is better to use a few extra words so that the information is clear. Copyright 1999 Alaska State Museum. Permission granted to reproduce for limited educational purposes. Rights and Responsibilities in History Storyboards for Exhibits Due Date –_________________ Storyboards allow the creators of an exhibit to visually plan the creation of the final product. It is essential to use this graphic organizer to plan, segment, and create each exhibit. It is also extremely important to be as detailed as possible when creating the storyboard. Each page attached will represent one section of the exhibit. Each section will contain visuals (clear pictures), documents, quotations, graphics of some sort (charts, maps, etc.), and/or pictures from interviews. ORGANIZATION is essential when creating an exhibit to further enhance the power of your final product. Important reminder: Be sure to segment your exhibit into the national theme of Rights and Responsibilities in History. It must be very clear all throughout the exhibit. Be very specific when explaining the contents of each section!! Refer to the NHD Guide for the dimensions of the exhibit. Most exhibits will be in the form of a tri-fold. All tri-folds must be constructed by the individuals creating the exhibit. Refer to examples in Mrs. McFarland’s room. Format Exhibit Component #1 – Rights and Responsibilities in History Exhibit Component #2 – Rights and Responsibilities in History Exhibit Component #3 – Rights and Responsibilities in History