File

advertisement

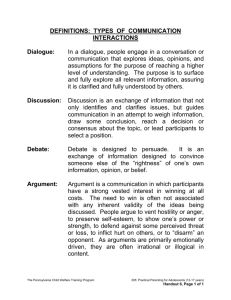

__________________________________________________________ UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES-BAGUIO DEBATE SOCIETY MODULE OUTLINE I. II. III. IV. INTRODUCTION: WHY GET INTO DEBATING? DEBATE FORMATS A. ASIAN PARLIAMENTARY B. BRITISH PARLIAMENTARY DEBATE MOTIONS A. OPEN B. SEMI-CLOSED/SEMI-OPEN C. CLOSED DEBATE TYPES A. VALUE-JUDGMENT B. POLICY V. SPEAKER ROLES A. PRIME MINISTER B. LEADER OF OPPOSITION C. DEPUTIES D. MEMBERS E. WHIPS F. REPLY SPEAKERS VI. VII. VIII. IX. POINTS OF INFORMATION ARGUMENTATION AND SUBSTANTIATION REBUTTALS ADJUDICATION _________________________________________________________ Basics I. WHY GET INTO DEBATING IN THE FIRST PLACE? 1. Debate helps you think critically. When you debate, you don’t rely on opinions. You ground points on arguments that are well thought out and logically sound. This necessarily means a debater thinks critically about issues, goes beyond surface analysis, and roots out what is normally ignored. Of course, this comes with training, so don’t give up if you weren’t able to weed out the important points in your first debate. 2. Debate fosters issue awareness. The one thing debaters should do, but are either too lazy or too confident to actually do, is matter load, i.e. read up on both current events and recurrent issues. When done rigorously, though, you not only enter debates with the proper weapons, but are made aware of what goes on in the world. Knowing the details of issues enables you to make informed judgments of how these issues should be tackled. 3. Debate cultivates balance and fairness. Again, opinions don’t matter in debate. You set them aside and open your mind to both sides of an issue. That way, you arrive at a whole picture instead of a half-baked judgment. Remember, you don’t get to be on one side of a debate forever, so be open to debating both sides of an issue. 4. Debate boosts self-confidence. There’s nothing like the feeling of demolishing an opponent’s case with a well-phrased rebuttal, standing behind a podium (or maybe in front of it) like you own it, and speaking to the adjudicator like you’re the expert. Debate is an exhilarating activity where the shy get to come out of their shell and express themselves. 5. Debate is plain good fun! Bonding moments with fellow debaters, memorable training wins (and losses), and other unforgettable experiences make debate worthwhile. __________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________ 1 __________________________________________________________ II. DEBATE FORMATS There are several different formats for debate practiced in high school and college debate leagues. Most of these formats share some general features. Specifically, any debate will have two sides: a Government side and an Opposition side. The job of the Government side is to advocate the adoption of the motion, while the job of the Opposition side is to refute the motion. In recent years, parliamentary-style debates, patterned from actual proceedings in Parliaments of different countries, have replaced the monotonous and less dynamic Oregon-Oxford and Cross Examination formats. Parliamentary debates (Asian and British Parliamentary formats) are more dynamic, since speakers are only given minutes to prepare speeches, as opposed to days in other formats. A. Asian Parliamentary Debates GOVERNMENT: PRIME MINISTER (7MINS, W/ POIs) DEPUTY P.M. (7MINS , W/ POIs) GOVERNMENT WHIP (7MINS , W/ POIs) GOVERNMENT REPLY (4MINS; PM OR DPM ONLY; NO POIs) OPPOSITION: LEADER OF OPPOSITION (7MINS , W/ POIs) DEPUTY L.O. (7MINS , W/ POIs) OPPOSITION WHIP (7MINS, W/POIs) OPPOSITION REPLY (4MINS; LO OR DLO ONLY; NO POIs) B. British Parliamentary Debates OPENING GOVERNMENT: PRIME MINISTER DEPUTY P.M. OPENING OPPOSITION: LEADER OF OPPOSITION DEPUTY L.O. CLOSING GOVERNMENT: GOVERNMENT MEMBER GOVERNMENT WHIP CLOSING OPPOSITION: OPPOSITION MEMBER OPPOSITION WHIP *POIs ARE ALLOWED IN ALL THE SPEECHES, SEVEN MINUTES FOR ALL SPEECHES. III. MOTIONS The topic for debate, which the affirmative side is supposed to defend, is known as a motion. In parliamentary debates, motions are usually termed as: THBT (This House believes that)… (Ex. THBT animals have rights), or THW (This House would)… (Ex. THW legalize jueteng in the Philippines) There are many ways in which a motion can be termed. Some motions are explicit in what they want debaters to debate about, while some need interpretation. The distinctions between these two ends of the motion spectrum give rise to what are called open, semi-closed, and closed motions. A. Open motions are motions that do not imply a relevant issue in themselves and need definitions to sort out its vagueness. “THBT the grass is greener on the other side” 2 is a perfect example of an open motion. Here, the Prime Minister, who is tasked to define a motion for everyone in the debate, should define what is meant by “the grass,” “greener,” and “the other side.” This could very well be a debate about job opportunities (the grass) being more fruitful (greener) abroad (the other side) as opposed to remaining in our country to work. Open motions really depend on what interpretations are made of open motions. They are rarely given out in debate competitions simply because the negative is at disadvantage, not knowing how the affirmative side will define the motion. B. Semi-closed (or semi-open) motions narrow down some details of what is to be debated upon, but leave room for the Prime Minister’s discretion to define. For instance, “THW legalize prostitution” is a semi-closed/semi-open motion. Although there is a need to define where and how prostitution is to be legalized, it is clear from the motion’s wording that the debate will be about prostitution (as opposed to other issues). B. On the other hand, value-judgment debates are assessments of certain ideas or phenomena, whether something has done good or bad, been beneficial or harmful, useful or not. Such motions are usually termed using “THBT,” since such motions call for an evaluation of certain things going on in status quo. Motions that call for celebration or regret of something also call for valuejudgment debates. More often than not, however, policy and value judgment aren’t necessarily two opposite poles. Sometimes, you can’t judge the effectiveness of a policy without looking at the merits or demerits of status quo. A valuejudgment debate may also call for a mechanism by which we can determine if a phenomenon is good or bad. We see, then, that policy and value judgment are ends of a continuum, and most debates lie in between these two ends. Case in point: Suppose you are faced with the motion “THW lay down the death penalty on drug traffickers.” Taking on a policy point of view, you would want capital punishment executed on all drug traffickers caught by authorities. C. Closed motions are the most self-explanatory of the three. When faced with a closed motion, there is no doubt as to what is to be debated upon and in what context it is to be tackled. But you might think this motion calls for a value judgment with regards killing drug traffickers as a deterrent to crime. You have a blend of policy and value judgment here. “THW create a separate sports league for homosexuals in the United States” is an example of a closed motion. Conversely, the motion “TH regrets US military presence in Iraq” may be merely a value judgment as to how Iraq has benefited or been harmed by the US invasion. IV. POLICY VS. VALUE-JUDGMENT DEBATES A. A policy debate usually ensues when a motion calls for a solution to a problem, through a policy. The object of this type of debate is answer whether or not the proposed policy solves the problem. Usually, motions that begin with “THW” are policy debates, since the motion calls for a plan of action. However, you might want to specify “regret” as a definitive action, say, driving out US soldiers from Iraq. Once again, policy and value judgment are not mutually exclusive. The point: know when a debate should focus on policy or value judgment, or when interplay of both is appropriate. 3 V. SPEAKER ROLES A. Prime Minister It is the duty of the Prime Minister (PM) to provide a definition that clearly captures the spirit of the motion. In addition to defining the motion, the PM should make sure that he/she also has arguments to back up his/her bench’s/side’s/team’s case. In defining a motion, the affirmative side is usually tasked to capture what is called the spirit of the motion. The spirit of the motion is what the debate calls for with regards the motion, what relevant issue is most evident and thus, what issue is most expected to be the topic of debate. In capturing this essence, the affirmative side should ideally avoid straying into topics not in line with the spirit of the motion. Now, just because the affirmative side has the power to determine the direction of the debate doesn’t mean it can define a motion any which way. The affirmative side must provide a fair and debatable motion that has a direct link to the motion (i.e. captures the spirit of the motion). Some nono’s in defining a motion are: 1. Truisms – Defining a motion as something already taken to be true. For instance, the motion “THBT tomorrow is a new day,” defined as the rising and setting of the sun as a basis for a new day, is truistic. The negative side cannot claim that the phenomenon of the sun isn’t a basis for a new day. Thus, there is no room for debate. 2. Squirrels – Ever notice how squirrels scamper away from the center of action? Squirreling, in debate, is likewise running away, but from the spirit of the motion. Defining the motion “THW legalize prostitution” as having to do with political prostitution, wherein a candidate “sells him/herself” to the most viable political party, is a squirreled definition. Obviously, this metaphorical definition of prostitution is not what the motion calls for; a more pressing issue, namely the sex trade, is what the debate requires. 3. Time/place sets – Placing the debate in unfair chronological or geographical contexts is also bad, for two reasons: either no issue exists in those contexts, or else the affirmative side has a monopoly of matter on those instances. The motion “THBT journalists should be armed” placed in the context of Brazil is a place set, since no pressing issue of attacks on journalists is present in Brazil. Likewise, placing the context of the same motion during the Martial Law years in the Philippines is a time set because past is past; there is nothing to be gained by debating about something that already happened. Make sure the context of the debate is fair for both sides. SETTING UP A VALUE-JUDGMENT DEBATE 1 BACKGROUNDER a. DEFINITION b. PARAMETER Determine the background of the issue you are going to debate upon. This can be done by stating the motion and saying why there is this issue in the first place. This will help the adjudicators a lot in understanding where the whole debate is directed to. Second, this can already include the definition of key terms in the motion, terms like legalize, celebrate, criminalize, etc. The parameter or the context as to where the debate is going to happen can already be established here. 2 PROBLEM Because the background serves as the account of past/present situations (i.e., what happens in status quo), the problem is about what’s wrong with status quo. Debates happen because there are existing problems to be addressed and clearly stating a wellpainted problem in every debate would offer a cause for changes. 3 STANDARDS Next, to further streamline the debate, standards should be clearly stated. The standards serve as measuring sticks of the debates. 4 They measure the effectiveness and validity of the arguments and they measure whether or not a side is achieving their goal. Standards are sometimes in the form of questions (general/specific phrasing of questions to be answered by teams in a debate), sometimes just clear statements like justification, social implications, etc. This is one of the most important contents of a set-up; it will be helpful not only to the adjudicator but equally to your side to include them every time you will do the set – up. 4 ARGUMENTS SETTING UP A POLICY DEBATE BACKGROUNDER a. DEFINITION b. PARAMETER Determine the background of the issue you are going to debate upon. This can be done by stating the motion and saying why there is this issue in the first place. This will help the adjudicators a lot in understanding where the whole debate is directed to. Second, this can already include the definition of key terms in the motion, terms like legalize, celebrate, criminalize, etc. The parameter or the context as to where the debate is going to happen can already be established here. 2 PROBLEM Because the background serves as the account of past/present situations (i.e., what happens in status quo), the problem is about what’s wrong with status quo. Debates happen because there are existing problems to be addressed and clearly stating a wellpainted problem in every debate would offer a cause for changes. 3 STANDARDS Next, to further streamline the debate, standards should be clearly stated. The standards serve as measuring sticks of the debates. They measure the effectiveness and validity of the arguments and they measure whether or not a side is achieving their goal. Standards are sometimes in the form of questions (general/specific phrasing of questions to be answered by teams in a debate), sometimes just clear statements like justification, social implications, etc. This is one of the most important contents of a set-up; it will be helpful not only to the adjudicator but equally to your side to include them every time you will do the set – up. 4 POLICY Then a policy and its concrete mechanisms should be clearly stated (this is only for policy debates) in order to establish the feasibility of the policy. To do this, first you have to determine the problem in status quo, and then state the specific mechanisms of your policy. Use the rule on what, who, when, and where in stating HOW your policy solves the problem being addressed. 5 ARGUMENTS The set-up should take a debater at most 3 minutes. This is in order for the PM to still have room for arguments. The set-up is one of the fundamentals of the debate, but the constructive contributions of the PM are the ones that will most matter at the end of the debate. One of which is the justification of a certain policy and why this is the best solution there is. Set-ups can prove to be advantageous to those who can do them efficiently. The only way to do that is to practice doing them. Also, a lot of adjudicators give premium to speaker roles, this means that a significant part of the merits given to the PM will come from the set-up. A lousy setup makes the whole debate a messy one, not only that, it can make a Government team lose a debate. B. Leader of the Opposition It is the role of the Leader of the Opposition to provide the clash to the Government’s case and provide arguments supporting his/her side’s case. In addition, he/she is expected to rebut some points raised by the Prime Minister. In cases when the Prime Minister presents a questionable definition, it is also the duty of the LO to challenge the definition. 5 1 CLASH A. STATUS QUO B. COUNTER-PROPOSAL 2 GROUNDS FOR CLASH A. STATUS QUO: BETTER OR EFFECTIVE B. STATUS QUO: SELF-CORRECTING C. COUNTER-PROPOSAL 3 4 REBUTTALS ARGUMENTS WHAT TO DO WITH A “QUESTIONABLE” DEFINITION, A.K.A. TIPS ON DEFINITIONAL CHALLENGES As Opposition team, debaters have to be dynamic enough to answer to Government side’s definition of the motion. This means being ready to scrap your prepared case (scrap prep) if Government presents an unexpected but viable definition. But what do you do when Government offers you one of those unfair definitions discussed earlier (truisms, squirrels, and time and place sets)? Let’s do an overview of each one first. Truisms, by definition, are already accepted as truth. Therefore, there is no point in debating one (try opposing the fact that the sun rises in the east!). Squirrels are harder to detect, but look out for them when Government strays from the spirit of the motion. An example is the motion “This house will legalize prostitution” defined as political partyswitching instead of sex trade. Time and place sets bring the debate to unfair contexts where issues are nonexistent or one-sided. An obvious example is debating on an event in your high school history textbook, which is over and done with, but there can be more subtle examples of time and place sets. IF AND ONLY IF DEFINITIONAL CHALLENGES ARE NECESSARY, here’s what to do as Opposition, specifically as the Leader of the Opposition (the only speaker in every debate—whatever the format—LICENSED to challenge the definition): EXPLICITLY STATE THAT YOU ARE CHALLENGING THE DEFINITION. STATE THE GROUND/S FOR THE CHALLENGE (TRUISM, SQUIRREL, ETC...) PROVIDE THE “RIGHT/CORRECT/SUPPOSEDLY FAIR” DEFINITION. NEGATE THE DEFINITION YOU HAVE JUST PROVIDED—PROVIDE THE CLASH FOR THE DEFINITION YOU INTRODUCED AS YOU ARE STILL THE LEADER OF THE OPPOSITION. Only the Leader of the Opposition is allowed to challenge the definition. If he/she doesn’t challenge, NO ONE else in the debate may do so. In Brit Parl, the Closing teams may choose which definition to support but closing teams are not allowed to challenge the definition anymore. That’s why definitional challenges are not advised, even if the Prime Minister’s definition is a bit flawed. A rule of thumb is that if you can debate the definition, don’t challenge it. You would just cause confusion…and you just might impress the adjudicators with your dynamism. So here’s a disclaimer for Leader of the Opposition ready to challenge: proceed with caution. Know what you’re doing and why. An empty challenge is the last thing adjudicators want to hear. \ C. Deputy Prime Minister and Deputy Leader of the Opposition It is the duty of each side’s second speakers to further develop their respective side’s case. They are expected, as other speakers are, to rebut points from the opposing side and rebuild their own side’s case if necessary. Furthermore, they should provide arguments that are distinct from those of their respective side’s first speakers. DEPUTY P. M. DEPUTY L. O 1 reiterate/clarify the stance 2 rebuttals 3 rebuild 4 delineate arguments from teammate 5 arguments 6 D. Member of the Government and Member of the Opposition In British Parliamentary debates, the members of both Closing Government and Closing Opposition provide what is called an EXTENSION. That is, each of the closing teams should forward a fresh case defending their respective side or tackle the debate from a perspective different from that of their opening teams. Of course, since their teammates are whips, who are rebuttal speakers, members are tasked to provide the constructive matter on these new perspectives. • 1 2 3 • 1 2 3 MEMBER OF GOV’T summarize OO’s case and rebut delineate from opening teams and arguments/contributions (extension) arguments/contributions MEMBER OF OPP summarize CG’s case and rebut delineate from opening teams and arguments/contributions (extension) arguments/contributions introduce own GOV’T WHIP & OPP WHIP “THEY SAY.........WE SAY.........WHY WE’RE BETTER” -ENUMERATES CONCESSIONS (AGREEMENTS BETWEEN BOTH SIDES, ACCEPTED POINTS BY BOTH TEAMS) -IDENTIFIES ISSUES (CONTESTATIONS, POINTS WHERE BOTH SIDES HAD SOMETHING TO SAY IN DISAGREEMENT WITH EACH OTHER) -DISCUSSES ISSUES TO THEIR TEAM’S ADVANTAGE (WHY ISSUES ARE TO BE CREDITED TO THEIR TEAM’S CASE) -ANSWERS THE QUESTION “WHY SHOULD WE WIN THIS DEBATE” WITH THE ISSUES AS THE MAIN GUIDE AND FOCUS TO ANSWERING THE QUESTION. F. Reply Speakers introduce own E. Government Whip and Opposition Whip It is the duty of the bench whip to provide a 7-minute SYNTHESIS of the issues discussed in the debate. The speech must not be constructive, as whips are the last speakers in the debate and cannot be rebutted. In their speeches whips should discuss how their respective sides addressed each issue and how their side wins on those issues. This does not mean, however, that they can just repeat what their teammates have already said; they should also provide new analyses of the issues that were brought up in the debate. In Asian Parliamentary debates, reply speeches can be given only by either the Prime Minister or the Deputy Prime Minister for the Government bench, and the Leader of the Opposition or by the Deputy Leader of the Opposition for the Opposition bench. Reply speeches are given for four minutes, within which the speaker must give a biased adjudication for their particular bench. -REPLY SPEECHES FOCUS ON SUBSTANTIAL TEAM CONTRIBUTIONS VIS-A-VIS TECHNICALITIES: • WHICH SIDE HAD MORE CONTRIBUTIONS IN THE DEBATE? MORE CONSISTENT AND SUBSTANTIATED? • WHICH SIDE HAD MORE RELEVANT ARGUMENTATION AND STRONGER REBUTTALS? • WHICH SIDE BETTER FULFILLED THEIR REASONABLE BURDENS AND SPEAKER ROLES? __________________________________________________________ 7 VI. POINTS OF INFORMATION POIs ARE TO BE RAISED ONLY AFTER THE FIRST MINUTE OF THE SPEECH UP TO THE 6TH MINUTE.THE FIRST AND LAST MINUTES OF EACH SPEECH ARE PROTECTED TO ALLOW THE SPEAKER TO START AND WRAP UP THE SPEECH UNINTERRUPTED. ONE CLAP AFTER THE FIRST MINUTE OF THE SPEECH MEANS THAT POIs CAN ALREADY BE RAISED AND ANOTHER CLAP AT THE 6TH MINUTE WILL SIGNAL THE END OF POI-RAISING AND TAKING. POIs ARE RAISED FOR PURPOSES OF STRATEGIC QUESTIONING AND NECESSARY CLARIFYING. POIs ARE NOT FOR BADGERING, HECKLING, AND PESTERING. RESPECT FOR THE SPEAKER TO WHOM THE POI IS ADDRESSED SHOULD STILL BE THE PRIMARY RULE. AS THE SPEAKER TO WHOM THE POI IS ADDRESSED, ON THE OTHER HAND, YOU ARE ENCOURAGED TO TAKE AT LEAST 1-2 POIs. DYNAMISM AND FLEXIBILITY OF SPEAKERS CAN BE SEEN THROUGH THE POIs THEY RAISE OR RESPOND TO. PROVE YOUR DYNAMISM AND FLEXIBILITY BY ACCEPTING POIs AND ANSWERING THEM WITH CONSIDERABLE DEGREE OF RESPECT. VII. ARGUMENTATION AND SUBSTANTIATION The most important skill that a debater should acquire is the skill to argue. Although there are a lot of styles in arguing, the structure of an argument is almost the same. It follows a simple pattern of logically linking the premises to a conclusion. It takes a lot of practice and debate experiences to acquire the skill. Here are some of the basics of argumentation for beginners. The first thing that we have to understand in arguing is that it is done in order to persuade. Before we can delve deeper into the details of argumentation, we first have to look at what a case is or elements that more often precede the argument/s. A case is the stand of a team in a debate. It is the basic point or angle of attack of a specific team. For the Government of course, the case is always a defense of the motion at hand, and for the Opposition, to oppose. In order to even have a case, it is fundamental that we understand the spirit of the motion and what it is calling for, especially the context where it lies and the proper venue where it is supposed to be debated upon. After that, a side should make the case or theme or team line, a point of attack where all the arguments are hinged upon. It is sort of the general notion or idea of why a team supports a given side of the issue may it be the affirmative or the negative. Next is determining the standards that measure the debate, this is a bit tricky for the Opposition because the Government has the privilege of choosing the standards, but it is enough to have a some sort of foresight of what the debate will be about. General ideas that can be derived from the motion give usable hints. For example, debates about curfews mostly talk about security, this can be a very good standard of a debate, and a side should take this standard into consideration in making their arguments. Next is the more specific part of determining exactly the arguments that each of the speakers in your team is going to talk about. The usual number of well analyzed arguments is around 2-3. With four or five arguments, it is doubtful that all can be well explained in a span of 7 minutes. So if you have 2 constructive speakers, maximum of three WELL-ANALYZED AND DEVELOPED arguments would suffice. First, let’s look at the label; the Tag or label or banner is a one sentence/phrase that catches the whole of the argument in a nutshell (title of the argument). For example, an argument for curfews can have this tag “curfews provide a higher degree of security”. Now the next step do is to explain how and why this will happen. This is where the analysis part comes in. The bulk of the argument is found here. In this part, the debater has to answer 3 fundamental questions. The how and why, which will guide the audience through the logic of your argument. The so what will lead the premises to conclusions in a logical manner. How and why can sometimes be answered at the same time (as they are interchangeable), often times they have to be treated as different questions. And the question of so what is the tie back of the argument. 8 This means that you have to tell the importance of this argument to your whole case. If you don’t do this, the argument will float in the air and will not be given full merit. Last is the example part of the analysis, it is not mandatory to have examples, but if you can find a very good example of your argument, this will strengthen it a lot. Qualification by example implies that in reality, your analysis applies. The error commonly done by beginners is that they argue by example, they think that examples can justify their claim. This is one fundamental mistake. At the end of a speech, it is also advised to summarize what the speaker talked about. This is again for purposes of clarity and in order to refresh the mind of the adjudicator of what the debater said in 7 minutes. ARGUMENTATION: 1. LABEL OF THE ARGUMENT (TAG, TITLE, CATCH PHRASE) 2. GIVING THE PREMISES OF THE ARGUMENT: HOW AND WHY? 3. CONCLUDING THE ARGUMENT: SO WHAT? 4. QUALIFYING BY EXAMPLE. • • • • • WHAT (ARGUMENT LABEL/TAG/CATCH PHRASE/TITLE) HOW (PREMISES OF THE ARGUMENT AND ARE WHY INTERCHANGEABLE WITH EACH OTHER) SO WHAT (TIE BACK/ CONCLUSION RECOMMENDATION) QUALIFICATION BY EXAMPLE OR EXAMPLE OF AN ARGUMENT ON THE MOTION “THIS HOUSE WILL IMPOSE CURFEWS ON MINORS”: 1. LABEL: Curfews provide a higher degree of security 2. A. HOW: since there will be a curfew at around 11 pm in the evening, people will be expected to be home already during that time, otherwise they are going to be detained if caught still outside. B. WHY: most crimes happen during this time of the night. The absence of people will prevent them from being exposed to such dangers. 3. SO WHAT: the importance of this argument is that it proves that the security measure in the form of curfew becomes a way of prevention for potential crimes that happen at night. This justifies the policy and supports the principle behind it. 4. PROVIDE EXAMPLE. Of course this is just a simple argument, in real debates, the analysis are deeper and more persuading. The strength of an argument lies in the logical linking of the premises to the conclusions. It is not enough to just state the label and assume that the adjudicator will have the common sense of asking and answering the how and why part of the question. This is one of the most common mistakes of a beginner; this is also the reason why they are always under timed. VIII. REBUTTALS Rebuttals basically require you to do two things: 1. Attack your opponents’ case and 2. Uplift your own. How exactly do you go about doing this? After hearing the previous speaker’s speech, you’re probably wondering about the validity of their facts and the essentials of their argument. In the course of their speech, have they mentioned any erroneous fact? For example, if they incidentally mentioned that the Philippines allowed gay marriage at any point in our country’s history, then it would best if you quickly pointed out that this supposed detail is false. That would put a rather large blow towards their case, especially if it was integral to their line of argumentation (i.e. definition, parameters) The next possible line of attack would be aimed towards their flow of logic. Has the previous speaker proven anything at all? Does their argumentation bear any trace of logic? We actually go back to the basics of argumentation. Were there any how’s and why’s in their speech that would helped in proving their case? If there was an obvious or not so obvious lack, then be sure to promptly point this out. For example, if any speaker were to argue that we must legalize prostitution because it has already 9 become rampant, there would be something clearly lacking in their claim. First we have to question how they came about in their assertion. Next, question the point in their assertion. So what if it’s rampant? Does it necessarily mean that it is good or to be legalized (or bad, for that matter)? Another possible attack to their argumentation would be to question their point of attack. In their analysis of the motion, were their arguments in any way assumptions, hypothetical, or in any way leading towards their actual conclusion? If they were, then be sure to point this out but, be sure to reinforce your allegations with good logic. For example, if they declare that crime rate is solely determined by a lack of education, you may choose to refute their claims by saying that poverty stands as a very salient reason for the proliferation of crime—and not necessarily lack of education. After attacking their case, you would want to proceed to an assessment of their arguments and yours. The establishment of your case requires you to do two things. First, reassert your case by stressing that your arguments are stronger than theirs. Then stress that your arguments are much more relevant to the issue at hand and would better solve the supposed problem. In stressing the strength of your case, you may utilize a wide variety of methods. You may utilize a cost-benefit model to either assert that your paradigm has far more benefits than theirs or contend that your benefits far outweigh the cost whereas their case has some troubling lack of safety nets for any possible ensuing cost. Or you may go about it once more by stressing the importance of your arguments and downsizing theirs. Okay, suppose that both teams had effectively delivered a perfectly logical assessment of the motion at hand. It is your task to direct the adjudicators’ attention to the aspects of the issue where you case bears more weight and benefits, and of course, negate the opponent’s case (by possibly throwing negative matter their way). The next level of assessment must take note the issue of relevance. Is their premise in any way relevant to the issue at hand? The issue of relevance is very much important in determining the victor in any debate. At the onset of their proposal, you must immediately ask yourself, “Is their proposal in any way addressing the real issue at hand?” There are some debaters who choose to pattern motions into specific experiences that they may have had in the past. If ever they have done so, it is your team’s task to point out whether their proposal is at all relevant to the problem, issues, and conclusions that may be generated in the course of debate. For example, if the motion set was “THW sacrifice the environment for urbanization,” there are several essential questions that must be initially asked: How did the Government define and delineate the concept of environment and urbanization? By the set definition, would the proposal entail the sacrifice as a prerequisite? Are there better alternatives in addressing the problem? To stress the importance of relevance, if the above motion was tackled as “slash forestry in order to relocate slum dwellers in deforested areas”, there are some needed questions of relevance. Is the problem of loss of space the main problem? Why do the slum dwellers choose urban migration in the first place? Is there an issue of urgency? If in the course of your analysis you happened to come across the fact that slum dwellers chose to relocate for purposes of livelihood, then you’ve necessarily displaced the solution of the Government because it did not address the problem headon. If in the end both teams had good premises, logic, and conclusions, then you have to once again stress that your points are ultimately better. You may choose to address issues of longevity, extensiveness, effectiveness, etc. In the end, rebuttals are not enough. Constructive cases and positive matter in the form of arguments are still the foundations of every winning debate team. -ATTACK THE LOGIC OF THE ARGUMENT (NOT BECAUSE WE WILL REINSTITUTE THE DEATH PENALTY IN THE PHILIPPINES DOES IT MEAN THAT CRIME RATES WILL SUDDENLY GO DOWN) -ATTACK THE FACTUALITY OF THE ARGUMENT (THERE IS NO SCIENTIFIC CORRELATION BETWEEN POLL AUTOMATION AND CORRUPTION-FREE ELECTIONS) 10 -ATTACK THE RELEVANCE OF THEIR ARGUMENT (IS THE ARGUMENT THAT “ERAP IS A CHARISMATIC FILIPINO LEADER” RELEVANT IN A DEBATE THAT ASSESS THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF HIS REELECTION?) THE REBUTTAL CASE One of the things that we should be careful about if we are the Opposition is the tendency to make a rebuttal case. A rebuttal case is a case full of negative matter without making any contribution/solution to a problem or to the discussion of the issue at hand. For one, a rebuttal case (especially in policy debates) is an unfair point of attack, because all the Opposition does is to say that the policy or the solution of the Government is wrong. The worse part is that the Opposition doesn’t offer any counter policy to solve a problem that exists in status quo. Second it is unfair because it makes the job of the Opposition relatively easier compared to the Government since the Government had to devise a policy to solve a problem and all the Opposition did is say that the policy is ineffective, leaving the problem unsolved. The way out of this is to limit the rebuttals in the rebuttal part of the speech. Always think about an alternative answer for a problem in policy debates, or an alternative perspective in value judgment debates. This will be considered as your positive matter and your contribution to the development of the debate. This way, you are not just saying that the policy of the Government is wrong, at the same time you are also proposing an answer to the problem as well. TAKING THE ADJUDICATOR INTO ACCOUNT In a parliamentary form of debating, the person/s we have to persuade above all is/are the adjudicator/s. The essential thing to remember is that, the adjudicator plays the role of an average reasonable person. Simply put, he/she is a “reasonably average” person who: 1. IS WELL-VERSED WITH THE RULES OF DEBATE (AS S/HE CAN RECOGNIZE AND APPLY THE RULES HER/HIMSELF) AND 2. MAY HAVE LITTLE OR NO KNOWLEDGE ON THE MATTER/MOTION AT HAND BUT CAN DECIDE ON MATTERS THAT ARE OF RELEVANCE TO THE DEBATE BY VIRTUE OF SENSE AND LOGIC. “LITTLE OR NO KNOWLEDGE” PRESUPPOSES THAT AN ADJ HAS NO TECHNICAL KNOWLEDGE IN A SPECIAL FIELD. Ergo, the PRIMARY AND MOST IMPORTANT ROLE OF THE DEBATER is to then guide the “average reasonable person” in the logic of the case. The adjudicator is the authority in debate. He/she is to be addressed as “Mr. Chair” or “Madam Chair” by debaters. Among the adjudicator’s duties are determining the winner of the debate; giving the adjudication or justification by highlighting strong points of the affirmative/negative through issue-based analysis; give constructive criticisms for the debaters’ improvements in succeeding rounds. Each person in the debate should observe proper decorum expected of people in ParliamenT. Mind you, debating is not all about persuading the masses to believe what you want them to believe. What you intentionally need to do is make the adjudicators believe that your case is plausible, logical, and that it stands. Adjudicators are average, reasonable people who MAY HAVE LITTLE OR NO knowledge about the issue but can completely understand logic and are experts of the rules of the debate. How are most debates judged? There is no hard and fast rule as to how to judge a debate. But usually it boils down to substantiation, structure, standards, speaker role 11 fulfillment, contribution, analysis and then some. Technically this can all be classified to the manner, matter and method. And yes, there is no easier and faster way to accomplish all of these than in training and constant practice. It is important that an argument or an issue is thoroughly discussed before an adj (adjudicator) so that s/he can fairly judge what has been discussed. As discussed in earlier sections on how to substantiate, it is important to discuss the how, why, so what’s of an issue. Only when you do so can the adjudicator get your point. It is important that the adjudicator thoroughly gets what you are trying to say, so one has to substantiate really well. For an argument to be considered “well substantiated,” it has to have a good label, analysis and probably some examples. A good label may add some oomph to an argument. The adjudicator usually takes note of the label/point of the argument. And a good label makes the adj remember the argument. But it does not stop there. A good label to an argument will not stand on its own. You have to substantiate it with the how, why so what’s. supposed to fill, not only will it make the debate a good debate if and when the roles are sufficiently accomplished, but also it is really what is expected. As discussed earlier in previous articles, the roles differ per speaker. As said there is no faster way to learn and be able to fulfill the roles than in training and constant practice. Contribution is a hard aspect to be adjudicated. A side of the house is expected to discuss the important issues in a debate and not only those which are minor issues. A side of the house is expected to look at the debate holistically and to not pick at just mere details of the issues of the other side. Analyzing an issue is a skill which can be developed through training and practice. The adjudicators are average reasonable people; they could see a good/brilliant analysis of an issue when presented to them. Surely there is no hard and fast rule as to how to analyze an issue. All of this actually boils down to manner, matter and method. A good structured speech makes adjudicators happy. Well, apart from the fact that a structured speech is incredibly easy to take down as notes, structured speeches are easy to understand. A structured speech involves coming up with good rebuttals, putting the best arguments first, and discussing the arguments. Although there is no easier way to learn how to structure a speech than constant training and practice, one is encouraged to come up with clear and concise statements that takes the adjudicators straight to the point or points and does not beat too much in the bush. Manner is HOW one presents herself and her arguments in a debate (DELIVERY). Diction, pronunciation, what type of shoes you wear DOES NOT matter to adjudicators, even if you arrive on the podium with unkempt hair, so as long as you presented your point well and got the adjudicators understanding what it is you are trying to say, then it’s fine. But also, some degree of respect to the podium, such as shying away from cuss words, shouting at your opponent and badgering, is expected. But I’m guessing you know general proper etiquette already. Another thing that the adjudicators look at is how the case line of one team is grounded on the standards of the debate. As discussed in earlier articles, standards are the measuring sticks of a debate; they determine what the debate is for. It is important that the teams discuss the debate in line with the standards. If they do not, they might as well be arguing about every aspect of the issue and the debate loses direction. For example, if the standards of the debate are for social beneficiality, and government responsibility, then the teams should, more or less, have their arguments in line with these two standards. Not following and fulfilling the standards, however, does not automatically translate to defeat or demerit. Matter includes the issues presented in a debate. Matter is expected from the debaters as the warranted, plausible knowledge of the issue. The adjudicators may not completely know the issue but they have some background on it. Matter is essentially the contribution/”substantives” in the debate. A debate, as we all know, is composed of speakers each with different roles to fulfill. It is important that the debaters fulfill the role that they are Method is fundamentally the organization of the matter. As opposed to manner, is the proper observance of debate technicalities like speaker role fulfillment, etc… __________________________________________________________ 12 13