Appendix C - American Association of Caregiving Youth

From Their Eyes…

Family Health Situations

Influence Students’ Learning and Lives

In

Palm Beach County, Grades 6-12

A Sub-Report of the “What Works” Project

Dr. Bertrand Miller, Project Director

Palm Beach Atlantic University

West Palm Beach, Florida

Prepared by Connie Siskowski, RN, MPA

Founder & President, Boca Raton Interfaith in Action

And Its

Comprehensive Family Caregiver Support Program

Funded by the

Quantum Foundation

www.boca-respite.org

From Their Eyes…

Family Health Situations Influence Students’ Learning and Lives

2

August 2003

The Changing Family

With the aging of our nation’s population and the changing of the composition and complexion of the family, come new challenges. The extended and expanded responsibilities of long-term care of persons with special medical needs because of illness, disability or aging are borne by family caregivers.

Nationally about 80% of all long-term care occurs within the home environment

(Feinberg, 1997). Today one often hears about the “sandwich generation” and the

“club-sandwich generation” – those families, especially baby-boomers, coping with various strains, stresses and stages of dependency of persons across the lifespan. (Russonello, 2001)

A family caregiver is that person who provides help or assistance to a relative or friend who has never had or who has lost full or partial independence as the result of illness, a disability or aging. Statistics in the United States indicate that one in four households are involved in family caregiving for someone over the age of fifty (National Alliance for Caregiving/American

Association of Retired Persons – NAC/AARP, 1997) and there are more than 25 million family caregivers over eighteen years of age. According to health economist Dr. Peter Arno, family caregivers annually contribute $257 billion in

(unpaid) labor and services to the economy. (Arno, 2002)

Another U.S. report describes that 26.6% of the population (fifty-four million persons) over the age of eighteen provide help to others (National Family

Caregivers Association, 2000). The assistance may be with activities of daily living such as bathing, eating, dressing or with instrumental activities such as finances, transportation or grocery shopping. An even earlier government study reports that 52 million people care for others who are over the age of 20. (U.S.

Dept. of Health and Human Services, 1998)

The landmark 1997 NAC/AARP study indicates that 47% of the family caregivers participating in their survey also have children under the age of

Connie Siskowski, RN, MPA 2

3 eighteen living at home.

This is no information about the ages of these children, the roles they assume, or the impact of family caregiving on their well-being and/or their education from both a learning and socialization perspective. These children and others who may be from single parent families, and the affect of the family health situation on their learning are the key issues that the What Works project helps us begin to understand.

To date, the majority of research and programs about family caregiving by young persons has been in England and Europe led by Dr. Saul Becker. Studies from the United Kingdom reveal that the average age of “young carers” is twelve years, 60% live in one-parent families, 61% are female and 29% care for someone with mental health problems. (Carers National Association, 1997) In contrast, research within the United States about youth who are under the age of eighteen as family caregivers is remarkably sparse. The studies that exist about these young persons have relatively few participants. (Gates, 1998; Beach, 1997)

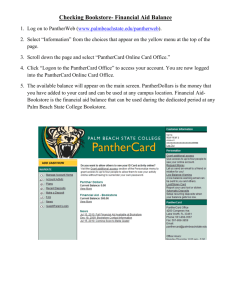

About What Works

A research team primarily from Palm Beach Atlantic College, now Palm

Beach Atlantic University, under the leadership of Dr. Bertrand Miller developed the What Works survey. The survey representing 12,677 students within Grades 6-12 in the public school system of Palm Beach County, Florida, gains insight into learning from the perspective of the student. The majority of the questions are indicators from a research-based education perspective.

(NSSE; Fitzpatrick, 1988) The instrument concluded with two questions relative to family health situations, the participation by students in assisting family members, and its impact on their academic performance. This writer, using personal knowledge, experts in caregiving and education along with the constraints of What Works space limitations, developed the family health questions.

Student Selection

In coordination with the Department of Research, Evaluation and

Accountability of the School District of Palm Beach County, the University

Connie Siskowski, RN, MPA 3

4 research team used systematic selection as the method for students to participate in the survey. As mentioned previously, the family health questions are limited in scope. The gender breakdown of students most closely represents that of the county public school district, however, other disparities in terms of actual representation by grade and racial distribution limit the ability to accurately generalize this information.

Students took part in the survey from various classrooms during the same time period in January 2002. There were no individual student identifiers.

Scanning was the method of data entry. Not all students completed the demographic information and therefore the total numbers for questions that are demographic specific vary. The sole purpose of this particular report on the

Family Health issues relates to the findings of the last two questions of the survey. It is, however, important to understand the key demographics of the whole survey sample.

The What Works Sample

Gender: The sample is nearly even for gender with 49.8% of participants being male and 50.2% of participants being female. For reasons unknown, 1,448 students (9.1 %) did not complete the gender answer. A possible explanation relates to its location on the answer form.

Race: Among all survey participants, there is some racial disparity from the general student population of the County within Grades 6 – 12. There is under-representation of Blacks and Caucasians and over-representation of

Hispanics and others.

Grade in School: There is a decrease in participants as the grade levels increase; this is consistent with the overall Palm Beach County public student enrollment by grade during school year 2001-2002.

First in the United States

To the best of our knowledge, this data is the first of its kind available from a diverse countywide student sample in the United States about the prevalence, the participation, and the impact of caregiving as it relates to a

Connie Siskowski, RN, MPA 4

5 student’s learning and academic performance. A recent (July, 2002) People magazine article about youth who are caregivers in single-parent households cites an estimate of 500,000 young caregivers in the United States. That number reflects only a portion of other early caregivers who may be in a shared caregiving situation or who may be in a role reversal with grandparents.

The What Works survey family health information answers four basic questions:

1.

Are there persons with special medical needs living in the homes of students or close by?

2.

If so, do students feel that their family health situation hinders their learning?

3.

Are students helping with the provision of care?

4.

If so, do students feel that this participation in care affects their academic performance at school.

Although the information relative to family health situations and young persons from this initial What Works Survey is limited, it is an important initial step for Palm Beach County and for this country. The family health results represent 11,029 students from 54 Palm Beach County schools. Of the 12,677 students who began the survey, 1,648 or 13% for unknown reasons, did not finish through question 86. Only those who answered the survey through

Question 86 and received instructions to continue or to stop the survey, serve as the analysis baseline for the Family Health component. It should be noted that, again for reasons unknown 53 students answered the Family Health questions but did not answer Question 86 and therefore were excluded from this analysis.

Limitations of Research

There are characteristics of the general population of Palm Beach County that complicate the interpretation of this data. They include:

The elderly population is abundant. These are the very persons who are more likely to need assistance, thus increasing the potential for persons in need of care. According to U.S. Census data from 2000,

Connie Siskowski, RN, MPA 5

6 the percent of the U.S. population over sixty-five years is 12.4%; in

Florida, it is 17.6%; and in Palm Beach County, it is 23.2%.

Among younger individuals ages 18-64 there is a higher than U.S. average of persons with activity limitations due to physical impairment or health problems. These adults further contribute to the pool of persons needing assistance. A 2002 Community Health

Assessment prepared by Professional Research Consultants indicates that while overall U.S. data shows 12.4% for this impaired population, Palm Beach County is 18.0% and the West Palm

Beach/Riviera Beach region is 22.6%.

A high incidence of HIV/AIDS may further contribute to the increased prevalence of persons with special medical needs in the home. The incidence of HIV/AIDS in West Palm Beach ranks the city fourth in the nation of new AIDS cases among metropolitan areas with populations greater than 500,000. Within all of Florida, the rate is 32.4% per 100,000; within Palm Beach County, the rate is 44.0% per 100,000. The equivalent national rate is 14.3% per

100,00. (Florida Department of Health, 2001)

The Family Health Questions

The questions concluding the What Works survey, numbers 87 and 88 were both decision point questions; students elected to continue if they met the criteria; if not they had finished the survey and could stop. Instructions for

Question 87 were:

IF YOU HAVE SOMEONE LIVING IN YOUR HOME WHO NEEDS SPECIAL

MEDICAL CARE BECAUSE HE/SHE IS SICK, HAS A DISABILITY, OR CAN NO

LONGER CARE FOR HIM/HERSELF, ANSWER THE FOLLOWING QUESTIONS. IF

YOU DO NOT HAVE SOMEONE IN YOUR HOME IN NEED OF SPECIAL MEDICAL

CARE, YOU HAVE COMPLETED THE SURVEY.

Similarly, after completing Question 87, students once again made a decision to continue or to stop based on the following instructions:

IF YOU HELP WITH THIS PERSON’S NEEDS, SUCH AS HELPING TO EAT,

BATHING, GETTING DRESSED, READING, HOUSEHOLD CHORES, TAKING THEM

Connie Siskowski, RN, MPA 6

7

ON ERRANDS OR DOING SHOPPING, ANSWER THE FOLLOWING QUESTIONS. IF

YOU DO NOT HELP THIS PERSON WITH HIS/HER NEEDS, YOU HAVE

COMPLETED THE SURVEY.

Student Responses

Survey results show 6,714 students who indicated that there was someone with special medical needs living with them or close by. Of these, 92.5% (6,210) answered that they participate in the care of this person. This represents more than one in two children (56.3%) of the baseline (11,029) population (12,677) who contribute to the care of a person with special medical needs.

Figure 1

14,000

12,000

10,000

8,000

6,000

4,000

2,000

0

Began survey (12,677)

Completed Q 86 (11,029)

Answered Q 87 (6,714)

Answered Q 88 (6,210)

Number of Students

It is of value to realize the racial characteristics of the students in Palm

Beach County and their participation both in the What Works Survey and in the

Family Health Questions. No one is exempt.

Figure 2

50

Palm Beach

County (84,000)

40

30

What Works

(12,529)

Question 86

(10,981) 20

10

Question 87

(6678)

0

Question 88

(6176)

Black White Hispanic Other

As evidenced earlier in this report, upon reaching the final two questions, students elected to end the survey or to continue. The 6,714 students (60.9% of

Connie Siskowski, RN, MPA 7

8 the 11,029) provided the prevalence of a family caregiving situation. The students then responded to a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree” to the statement, “Living with this person in need of special medical care hinders your learning.” The majority of students, more than three out of five, have “No Opinion”, “Disagree” or “Strongly Disagree” that the person with special medical needs hinders their learning. However, a remarkable 38.5% indicated that they feel this family situation hinders their learning.

Students who completed the subsequent question indicated their “ handson” helping in the participation of care. The question then asked, “How does helping this person affect your academic performance in school?” The single answer choices and responses to Question 88 included:

It interrupts my thinking and/or time studying – 24.2%

I do not complete homework assignments – 17.1%

I miss school/after school activities – 13.2%

I have experienced more than one of the previous choices – 12.7%

While nearly one third of the students indicated that helping has no effect on their school performance, the majority of the students (67.3 %) answering this question indicated that helping this person does affect their academic performance.

As with the previous indicator relative to the hindering of learning, there is a highly statistically significant (p<.001) difference in responses between boys and girls for both questions. Furthermore, students differentiated between their response to “hinders learning” and the choices they could select for affecting their performance at school. This is true for various categories. Visual representation augments cognitive synthesis of this impact as represented within the gender responses in Figure 3 and Table 1:

Connie Siskowski, RN, MPA 8

9

Figure 3

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Has person with need (6089)

Helps person (5612)

Affects school performance (3723)

Hinders learning (2326)

Male (5066) Female (5084)

Table 1- Gender Male Female

Has person in home with special needs 3399 2690

Agrees/strongly agrees hinders learning 1331 995

Percentage responses within gender 39.2 37.0

Participates in care

Affects academic performance

3159

2232

2453

1491

Percentage responses within gender 70.7 60.8

Of the 10,981 students who completed the survey through the baseline

Question 86 and who identified themselves by race, the caregiving responses extend across all races. (Figure 4, Table 2) Black students had a highly significant response (p <.001) that the person with special medical needs hinders their learning while white students had a significantly lower response; (p <.001).

While there are some variations among racial categories, students feel the impact of persons with special medical needs on their academic performance.

Furthermore, the majority provides assistance and therefore, are young caregivers.

Connie Siskowski, RN, MPA 9

10

Figure 4

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Black (2821) White (4792) Hispanic

(2237)

Other (1131)

Has person with need (6678)

Helps person

(6176)

Affects school performance

(4151)

Hinders learning

(2567)

Table 2 - Race

Has person in home with special needs

Agrees/strongly agrees hinders 905 876 517 learning

Percentage responses within race 43.2 35.2 37.4

Participates in care

Black White Hispanic Other

2096 2489 1380

1976 2281 1258

713

269

37.7

661

Affects academic performance 1420 1458 835

Percentage responses within race 71.9 63.9 66.4

438

66.3

Likewise, there are variances among grades, presented in two sets, one for middle (Figure 5, Table 3) and one for high school (Figure 6, Table 4). This data is consistent with data from England indicating the average age of a young carer is twelve (Carers National Association, 1997).

Connie Siskowski, RN, MPA 10

11

Figure 5

20

15

10

5

0

40

35

30

25

Grade 6 (1403) Grade 7 (1259) Grade 8 (1247)

Has person with needs

(3909)

Helps person (3617)

Affects school performance

(2329)

Hinders learning (1516)

Table 3 - Grade

Has person in home with special needs

Agrees/strongly agrees hinders learning

Percentage response within grade

Participates in care

Affects academic performance

Percentage response within grade

Figure 6

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Grade 9 (717) Grade 10 (481) Grade 11 (416) Grade 12 (292)

6 7 8

1403 1259 1247

596 467 453

42.5 37.1 36.3

1285 1178 1154

821 749 759

63.9 63.6 65.8

Has person with needs

(1906)

Helps person (1744)

Affects school performance (1200)

Hinders learning (682)

Connie Siskowski, RN, MPA 11

12

Table 4 - Grade

Has person in home with special needs

Agrees/strongly agrees hinders learning

Percentage response within grade

Participates in care

9 10 11 12

717 481 416 292

249 155 161 117

34.7 32.2 38.7 40.1

661 432 384 267

Affects academic performance

Percentage response within grade

448 291 264 197

67.8 67.4 68.7 73.4

Among high school student responses, the impact on learning somewhat diminishes during the early years and then increases during junior and senior years. While the percentage response of ninth graders is highest, when evaluating within the grade itself, the percentage of students for whom this situation hinders learning is highest among seniors. The response most frequently reported by all students is that helping this person “interrupts my thinking and/or time studying”. There were 689 students or 12.9% of young caregivers indicating that more than one choice affected his or her performance at school. This reflects 6.2% of the whole sample of 11,029 students.

Implications

Several aspects of this report require more investigation and understanding. They include:

Learning the specifics of the family health situations and the caregiving in which the youth are participating

Exploring resource utilization of community support services by the families of these students, including those of cultural diversity

Developing professional education materials to assure that persons who are influential in the lives of students such as guidance counselors, teachers, school nurses and youth clergy, have an understanding about family caregiving and the issues that youth are confronting

Connie Siskowski, RN, MPA 12

13

Evaluating the need to develop additional resources including information, education and support services geared toward meeting the needs of youth

Determining the ability of education, healthcare and community support services to collaborate on behalf of supporting young family caregivers

Assessing the short and long-term value of life experience learning in terms of overall student education

Reviewing existing policy and pending legislation such as the

Lifespan Respite Bills to assure the inclusion of young caregivers.

Therefore, although this population sample does not exactly mirror the student population of Palm Beach County public schools, the findings warrant further research, attention, and collaborative remedy toward improving the learning experiences, the opportunities, and the lives of students. The What

Works survey has taken a chance – it has broken new ground within the United

States. Discovering new information is a risk. With risks come challenges.

One major challenge is in obtaining the financial resources to continue this compelling work. Concurrently steps must occur to bring together a multidisciplinary team. Education, health and community support including faithbased services can join forces to develop programs that will assure that families and children have the resources they need and deserve so that young people can accomplish their primary task of becoming educated citizens.

For further information contact:

Connie Siskowski, RN, MPA

PO Box 811525

Boca Raton, FL 33481-1525

561.999.9198 consisko@bellsouth.net

Dr. Bertrand Miller

Palm Beach Atlantic University

901 S. Flagler Dr.

PO Box 24708

West Palm Beach, FL 33416

561.803.2360 millerb@pba.edu

Connie Siskowski, RN, MPA 13

14

References

Arno, P.S., Economic Value of Informal Caregiving . Montefiore Medical Center

& Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Orlando, FL. February 24, 2002.

Beach, D. L. (1997). Family Caregiving: The positive impact on adolescent relationships. The Gerontologist, 37, 233-238.

Carers National Association. (1997). Still Battling? The Carers Act one year on.

London: Author.

Feinberg, L.F. (1997). Options for supporting informal and family caregiving.

Family Caregiver Alliance for the American Society on Aging, San

Francisco.

Fitzpatrick, K. A. (1988). Indicators of schools of quality (vol. 1). Schaumburg,

IL: National Study of School Evaluation.

Florida Department of Health. (2001). Public health indicator reports, 1998-

2000. Tallahassee: Author.

Gates, M. F., & Lackey, N. R. (1998). Youngsters caring for adults with cancer.

Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 30,11-15.

Levine, C. (Ed.) (2000) Always on Call. United Hospital Fund, NY.

National Alliance for Caregiving & The American Association of Retired Persons

[NAC/AARP]. (1997). Family Caregiving in the US: Findings from a

National Survey. Washington, D.C.: Author.

National Family Caregivers Association. (2000). NFCA Caregiver Survey.

Retrieved June 4, 2002, from www.nfcacares.org.

Russonello, B., Stewart, (2001). In the Middle: A Report on Multicultural

Boomers Coping with Family and Aging Issues. AARP, Washington, D.C.

Schindehette, S., Fowler, J., Poilon, Z., Heiling, S. (2002) Heroes at home,

People. 7/15/02, 52-60.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (1998). Informal caregiving; compassion in action. Washington, DC: Author.

Connie Siskowski, RN, MPA 14