Determinants Of Foreign Direct Investment In Central And

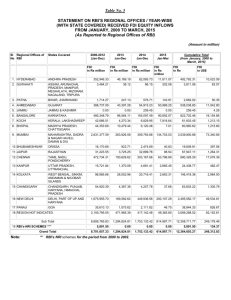

advertisement