Corporate%20Social%20Responsibility

advertisement

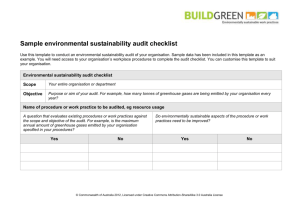

Auditing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Overview In recent years changes in the nature and provision of public services have resulted in shifts in the expectations of stakeholders. Public sector organisations (PSOs) have always had to respond to the needs of their communities but the number, range and diversity of these needs is growing. This has also resulted in the emergence of the public as “stakeholders”. As a result stakeholders in PSOs are becoming more discerning about the organisations that serve them and they draw upon an increasing range of reported information to help them in this. In addition to more conventional measures of activity, their social, ethical and environmental (collectively referred to as CSR) performance is now coming under increasing scrutiny and organisations need to ensure that risks and opportunities in these areas are treated appropriately. CSR’s relationship with risk management and other management systems Current approaches towards risk management are based upon the principles outlined in the Turnbull Report (ICAEW 1999) and this work has also become prevalent in the public sector. ‘Turnbull’ questions whether significant risks are being identified and assessed on an ongoing basis and this includes the existence of effective management systems with their associated control frameworks. The list of risk types cited by Turnbull includes health, safety, environmental, reputational and business probity risks; all of which fall within the area of CSR-based risks. Complying with ‘Turnbull’ requires organisations to ensure that there is appropriate management and control of such risks where they are considered significant to its business. The audit assurance provided through traditional methods in conventional areas of audit is, in principle, no different to the audit of risks in specialised fields: the audit of CSR has the effect of moving organisations closer to meeting the full requirements of Turnbull. This move towards a wider set of business risks will require assurance on CSR-related risks and auditing CSR serves the following objectives: measuring the core aims of the organisation (defined by its mission statement); identifying specific aims resulting from stakeholder consultations; measuring societal aims through the concerns established in the societies that the organisation operates in; use as part of the strategic management and operational planning processes so that existing processes could be reviewed with regard to social responsibility; identify strengths and weaknesses in policy and practice; identify improvements; measure progress in relation to implementing CSR; and, obtain ownership and participation of those able to contribute to CSR for their organisations. Internal Audit’s role The IIA UK and Ireland (2003) promote the view that internal audit’s role in CSR is, like its role in risk management generally, dependent upon the organisation that it is Page 1 employed to serve. However, an internal audit function can provide value to their organisation in the area of CSR through providing assurance upon: the CSR approaches of the board and senior management; and, how well aligned the organisation is with its stated values, policies and codes of conduct. As such there is a strong relationship between CSR and risk management (see above), demonstrating the consequent benefits of good CSR practice upon the business risks to an organisation in the form of increased employee morale and motivation, lower staff turnover and absenteeism, reduced waste and costs on the regulatory compliance of health and safety. The management of CSR (and CSR risks) is no different in this sense in that there are strong business case and competitive advantage arguments in favour of organisations that engage in effective CSR. In general terms, organisational activity for CSR falls into two main areas: carrying out existing, routine operations in a socially responsible way (eg ethical purchasing) and/or undertaking specific CSR-type activities (eg environmental management initiatives). Within this internal audit has a distinct role to provide assurance on how well the CSR risks are being managed: this is both consistent with the overall practice of managing risks within the context of Turnbull and serves to strengthen existing risk management practice within an organisation. Internal audit’s approach can take the form of one or a combination of: Social Audits: a process that measures an organisation’s social activities (ie those that affect its immediate community and society) in how: Employees and other stakeholders perceive the organisation; The organisation fulfills its aims; and, The organisation works within its own value statements. In short, social auditing assesses the social impact of an organisation in relation to its aims and those of its stakeholders. Social auditing is considered to be founded on the principles of disclosure and openness as the dialogue with stakeholders has to be reciprocal, continuous and honest. An example of social auditing in the public sector may be an assessment of an organisation’s activities in the area of its social inclusion programmes (eg widening participation initiatives in FE/HE). This may be related to a set of corporate objectives that identify the need to engage with or serve better a group of the community whose needs are currently not well met. Ethical Audits: an audit that tests the consistency of values throughout an organisation so that senior managers can be informed about any ethical vulnerabilities. Ethical audits are often seen as an internal management tool that is used as a way of listening to the views of stakeholders, particularly those that work within the organisation. Areas covered in an ethical audit might include: Establishing the values held by an organisation and how they were derived; Assessing whether these values are consistent with the way the organisation operates and what it does; and, Page 2 Measuring whether they conform with the values of those working in the organisation. An example of ethical auditing is the refinement of traditional areas of an organisation’s operation such as investments or purchasing to include an assessment of how ethically these activities are undertaken. Ethical audits consider how effectively policies determine ethical decision-making, ie if the organisation places business with companies who have good track records in staff welfare, human rights or if the organisation avoids investments in areas such as arms manufacturing, tobacco, etc. There are close links to this type of audit and the social audit given that each considers the effect upon an organisation’s stakeholders and how they perceive the organisation. Environmental Audits assess the effectiveness of how well the organisation’s policies and practices comply with relevant environmental regulations and how well environmental impacts are managed. There is a strong link between social and ethical auditing and combined with environmental auditing these are seen as a means of measuring and influencing how an organisation manages its reputational risk. Many public sector organisations already operate in this area through audits of environmental management systems and this is covered in this volume at: (need to insert link here to Don Simpson’s paper on Env Audits). Other examples of audit activity in this area may include the assessment of specific environmental projects for their cost and effectiveness (eg the effectiveness of introducing a recycling scheme) or ensuring proper reporting controls are in place to meet the requirements of the recently introduced EU carbon emissions trading. The following factors are key components to delivering an internal audit approach to CSR: audit focus; auditing stakeholder processes; audit methodology; use of specialist skills; and, proportionality. Audit Focus The focus of activity for internal auditors should be to provide managers and their audit committee with assurance that these risks are being effectively managed and that any approach to auditing CSR should not be seen as a separate process but should incorporate the principles of embedment and integration. Existing models of riskbased audit approaches should be adapted, where necessary, to include the additional considerations of CSR. This will reduce the potential for an assurance gap and enhance the perceived value of the internal audit service. This approach may take some time to achieve and internal auditors have a significant role to play in educating their clients in these new risks and their potential impact upon the business objectives. The internal audit focus upon CSR should cover all aspects that are appropriate to the business of a PSO. These include the assessment of how responsibly the organisation Page 3 conducts existing operations as well as the audit of any discrete projects or activities that have specific CSR theme (ie their main objectives are linked to any CSR aims of the organisation). The audit approach should also seek to provide managers and audit committees with an indication of how closely their stated values towards responsible business practices are with actual operational activity. Auditing stakeholder processes Stakeholder processes can be defined as those activities that organisations employ to identify their stakeholders, how they engage with them, how their needs are identified and met, etc. Successful CSR approaches demonstrate that stakeholders are integral to the management of CSR processes and any subsequent audit process. An organisation’s stakeholders consist of a long and potentially difficult to manage list of groups have significant power and influence in the reputation and public confidence of an organisation. They therefore need to be considered as part of any CSR audit. To make the audit of stakeholder processes practical and achievable, some prioritisation is necessary to establish a representative audience on the basis of those stakeholders who are core to the mission and values of the organisation and those who are interacted with the most. Evaluating the effectiveness of stakeholder management programmes by assessing how managers: identify stakeholders and map their relationship with the organisation; identify the ‘stake’ that they have in the organisation This can often be a difficult area to measure, because whilst some aspects are easily quantifiable (money, materials), others are not (reputation); analyse how well the stakeholders’ needs are being met in terms of their invested ‘stakes’. This may identify potential changes in the overall mission and vision or changes in the relationship of the stakeholder; and, adjust organisational aims and approaches to meet the stakeholders’ needs, although this exercise may identify competing requirements upon the organisation as a result of the different stakes of each holder. Given that stakeholders are central players in the successful adoption of CSR, it follows that management will require some independent assessment of how well such processes are functioning. The inclusion of assessing stakeholder management into an audit approach provides a basis for managers to receive assurance on how well this process is being managed. The consideration of stakeholder processes should be included in social, ethical or environmental audit. Risk-based and other audit methodologies The use of a risk-based approach does not preclude the use of other methods such as systems-based approaches or the verification of metrics, performance indicators or other measures and internal auditors should make use of these approaches in support of the overall risk-based audit method, wherever appropriate. In addition, some management models are used by internal auditors to enable the external or social elements of an organisations to be assessed /managed. Such models include the European Framework for Quality Management (EFQM) which is also called the Business Excellence Model and the Balanced Scorecard approach and the use of such models may also be of value. Page 4 Use of specialist skills Whilst it is recognised that internal audit is an accepted process with proven structures and disciplines, there is a need for specialists and expert resources to play a role in the overall assurance arrangements for the audit of CSR. Internal auditors already provide their organisations with assurance on the control frameworks in place and this typically covers responsibility and management arrangements, governance, risk and reporting. This is not anticipated to change but where specific issues require expert resources, these should be used, both as a means of specialist help and opinion in an area requiring such knowledge and as a basis for developing and training auditors in these areas so that their own knowledge and competencies are enhanced. In the interests of economy, internal auditors should look to make use of expertise within their own organisations in the first instance. The use of multiple agencies should be considered as a necessary part of any audit planning and the principle of working with other agencies is covered separately in the volume at: (link to working with others pages). Proportionality The audit effort used in auditing CSR risks should be proportionate to those risks. Where risks are not explicit, say in the instance of auditing how responsibly existing operations are discharged, this may require a level of audit coverage that does not require in-depth assessments but provides a high-level but wide ranging approach. Other areas may require a narrower focus but in more depth. Other considerations The absence of agreed reporting standards have also hindered the further and wider emergence of CSR and any assurance that can be placed upon it. Despite this lack of clarity, one standard is generally favoured by organisations and companies engaged in reporting on CSR activity, this is the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). From this has emerged the AccountAbility 1000 Framework which is an assurance standard on reporting sustainability and is based around a series of process and foundation statements designed to improve the quality and credibility of CSR information through independent verification. There is little in the way of guidance for internal assurance providers, such as internal auditors, in ensuring that systems and processes are of sufficient rigour and the main focus of the standard is for external assurance providers such as an organisation’s external auditors. Despite this, the standards promote many useful principles that internal auditors could use as a point of reference. The authors of the standards recognise that it is still a developmental model and will continue to adapt and grow in light of new knowledge. Further Reading AccountAbility / Institute of Social and Ethical Accountability, (1999), Accountability 1000 (AA1000) Framework: standards, guidelines and professional qualifications [Online], available from www.accountability.org.uk. Page 5 AccountAbility / Institute of Social and Ethical Accountability, (2003), AA1000 Assurance Standard [Online], available from www.accountability.org.uk. Elkington, J., (1998), Cannibals with Forks: the Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business, London: Capstone. Evers, P., Harmon, W.K. and Ivancevich, S.I., (2004), Sustainability Reporting: implications for internal auditors, Internal Auditing, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp21-27. Federation des Experts Compatables Europeens (FEE), (2003), Benefits of Sustainability Assurance [Online], available from www.fee.be/publications/main.htm . Institute of Internal Auditors – UK and Ireland, (1999), Ethics and Social Responsibility, Professional Briefing Note No. 15, London. Institute of Internal Auditors – UK and Ireland, (2003a), Ethical and social auditing and reporting – the challenge for the internal auditor, Professional Issues Bulletin (May 2003), London. Institute of Internal Auditors – UK and Ireland, (2003b), Embedding risk management into the culture of your organisation., London. Nitkin, D. and Brooks, L.J., (1998), Sustainability Auditing and Reporting: The Canadian experience, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 17, pp1499-1507. Rayner, J., (2003), Managing Reputational Risk – curbing threats, leveraging opportunities, Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons. Waddock, S. and Smith, N., (2000), Corporate Responsibility Audits: Doing well by doing good, Sloan Management Review, Vol. 41, No. 2, pp75-83. Wallage, P., (2000), Assurance on Sustainability Reporting: An auditor’s view, Auditing, Vol. 19, pp53-65. World Business Council for Sustainable Development, (2000), Corporate Social Responsibility: Making Good Business Sense, p10. Page 6 Appendix 1: Definition and development of CSR There are a number of definitions of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), but the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (2000) defines it as: “the commitment of business to contribute to sustainable economic development working with employees, their families, the local community and society at large to improve their quality of life.” (p10.) Rayner (2003) develops the definition of CSR to explain its components in more detail: operating in a way that goes beyond basic legal compliance and permeates all areas of operation – from the board downwards; considering the wider impacts on, and contributions to, society and the environment: minimising negative impacts and maximising positive impacts; identifying, assessing and addressing social, ethical and environmental risks; displaying responsibility, fair dealing and respect for human rights in relationships with stakeholders (both internal and external to the organisation); taking into account and responding to the needs and expectations of diverse stakeholder groups on which future success depends; and, balancing all of the above and integrating them into decision-making, strategy, corporate governance, management and reporting systems. CSR can be seen as a natural extension of existing initiatives such as customer care, supply chain management and corporate philanthropy. CSR has developed in response to environmental and social events and its roots are in the environmental development of the 19th Century. This gained further popularity in the 1960s and 1970s with the emergence of pressure groups such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth and in 1980s through events such as Shell Oil’s activities with the Brent Sparr oil rigs and the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Organisations have always been concerned with their social impact but a number of developments have given impetus to this aspect of CSR. The most significant being Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the UN in 1948 and the European Union’s Social Action Programme in 1973 that was later updated its through its ‘Social Charter’ in 1989. Page 7