Additional case studies

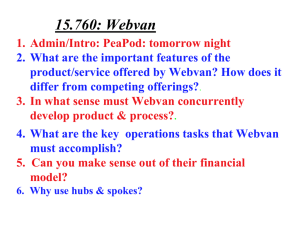

advertisement

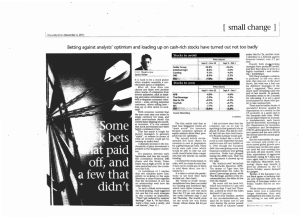

Connectis March 2001/E-reality Teaching e-business and e-commerce requires realism in the light of the ‘dot-com failures’. These are discussed in a Focus On section in Chapter 2, but this extra case study is included to highlight the reasons for some of the failures. Death of the dotcom dream by Andrew Hill and Caroline Daniel March 22 2001 © Financial Times For most Americans, November 7 2000 – election day – marked the start of a drawn-out period of uncertainty about who would be their next president. But for executives and employees of Pets.com, the online pet products retailer, it was the end. On that Tuesday, the company announced it was beginning “an orderly winding down of its operations”. It was an ignominious finale for a company which, less than six months earlier, had proclaimed that it would be the only one to survive the fall-out in the sector. In many ways, it was a symbolic moment. Pet products e-tailers – which sprung up around the world – epitomised the wild over-investment in some internet stocks. Pets.com had itself come to market only in February last year, just before the bubble burst. Its initial public offering was backed by Merrill Lynch and endorsed by the investment bank’s star internet analyst, Henry Blodget. It was part of the network of startups partly owned by Amazon.com, the biggest e-tailer of them all, and its IPO [initial public offering] was preceded by a barrage of advertising, featuring its sock-puppet dog mascot. Year of living dangerously In December, Jeff Bezos, Amazon.com’s founder, described 2000 as “a great business year and a terrible stock market year”. The rapid dwindling of investor interest in internet stocks drained $10bn (£6.9bn) from the market value of his one-third share in Amazon. But as pure-play internet companies began to close their doors, there were plenty of people complaining that it had been a terrible business year as well. According to Challenger, Gray & Christmas, a Chicagobased outplacement consultancy, 41,515 people lost their jobs at nearly 500 US internet companies last year; and a fifth of those companies went out of business. The lay-offs became so common that a host of deathwatch sites emerged to chronicle them – and make virtual bets on the next companies to go down. Often employees found their own companies’ demise heralded on these sites before they had any idea of underlying problems. Postings from disgruntled, laid-off employees became commonplace. There was also a stark contrast between the first and second half of the year – 87 per cent of dotcom cuts were made between June and December, mostly from internet companies in the financial, consulting, information and retailing sectors. Companies such as Pets.com, and the UK’s Lastminute.com, which launched initial public offerings before the peak, were lucky in one sense. At least they had cash in the bank. But they were burning it at a frightening rate. So much so that “burn rate”, not user visits, became a significant way to evaluate the longterm prospects of survival for an internet company. By the end of 2000, with the Goldman Sachs Internet Index down 77 per cent from its peak in early March, there was little or no chance that the survivors could return to equity investors for more. Private equity funders, many of whom had adopted a “spray and pray” approach to investing, also slowed the pace of new investment. © Marketing Insights Ltd 2004 Some claimed to have spotted the writing on the wall well before last year. Alan Beasley, a partner with Redpoint Ventures, a Silicon Valley venture capital firm, said his colleagues were shown six different business plans for online pet supply companies in the US in early 1999. “That’s when the lightbulb went on and people started thinking, ‘Something’s not right here’,” he said last summer. Bill O’Connor, a creditors’ rights lawyer with the New York firm Buchanan Ingersoll, said big investors and creditors began calling in their loan workout experts in November 1999 to chase up bad loans to internet companies. “By December holiday parties a lot of people were talking about the coming bursting of the bubble,” he recalled. Around the same time, US e-tailers were realising how difficult it was to fulfil online demand for Christmas gifts. ToysRus.com was forced to warn that it would not be able to deliver some goods in time for Christmas. But even among sceptics, few forecast the magnitude of the collapse. Byron Wien, Morgan Stanley Dean Witter’s US strategist, correctly predicted in January 2000 that the internet sector would “finally meet its Waterloo”, but he said content and retailing stocks would correct by only 50 per cent, whereas many lost 80 or 90 per cent of their value. “If anything, I understimated the destruction,” he wrote at the beginning of this year. Party poopers Indeed, in January 2000, the Nasdaq Composite index, home to many of the new-minted dotcom companies, still had a long way to go before it hit its peak of more than 5,000 in mid-March. In Europe, the internet party had only just got going. The sense of gloom which fanned out from the Silicon Valley capitalists, some of the earliest internet investors, did not start to knock sentiment in Europe until spring 2000. After all, the flotation of Freeserve, the UK internet service provider which marked the turning point for internet flotations in Europe, had only come in late July 1999. Investors were reluctant to pay too much attention to the warning signs emanating from the US. Instead, the European public equity markets were energised by a feverish rush to catch up with the US markets, where five years of heady market valuations had helped support and encourage private equity funders to channel billions of dollars of new funds to new internet companies.”Everything happened in Europe on an accelerated timetable,” says Paul Zwillenberg, partner at KPE, a UK-based media consultancy. “The feeding frenzy started in the summer of 1999 and came crashing down in spring 2000, whereas in the US it had lasted from 1995.” The fact that Europe was at an earlier stage of development did little to protect it, however, from the downdraft affecting its more mature US peers. Ramzi Nahas, managing director of Fimadex, a French consultancy advising start-ups, said: “The internet gold rush was one of the world’s shortest. It only lasted 18 months for us. The cycle was not long enough for France to establish its Amazons and Yahoo!’s.” The risk now, according to Mr Nahas, is that some projects that were likely to become financially viable will not be given that chance. “When financial backers move from one extreme [risk-taking] to the other [risk aversion], they leave no room for the middle ground,” he says. “There are quite a few start-ups now begging for one last chance but they are unlikely to get it. In such conditions, some web ventures are likely to go belly up just weeks before they could have become profitable.” Even though the heady valuations were enjoyed for a shorter time in Europe, they were underpinned by the same conditions that had created a five-year bull market for US internet stocks: scant data, blanket media coverage, starstruck commentary by investment banking analysts and insatiable demand for growth stocks. In the wake of their initial public offerings, the youthful founders of new dotcoms in the US were paraded through the studios of CNBC, the business news channel that built its reputation and its viewer figures on the back of the US bull market. “Some of them came in with only an idea. You asked them how they would make money and they would come up with some half-baked idea – and the stock would rise $5 [£3.50],” recalled Ron Insana, one of the © Marketing Insights Ltd 2004 best-known commentators on the network, last autumn. “I was as sceptical as I could be for some time – and then I began to feel I was missing something.” Shooting the bull The most brazen of the European wannabe entrepreneurs began to emerge in late 1999 and early 2000, reassured by the fact that online businesses – unlike any other business – seemed not to need capitalintensive amenities such as warehouses and production lines. For a time, what mattered was the ability to construct a bullish growth narrative around an idea, and have the nerve to sell that to prospective investors. One European internet entrepreneur, based in Silicon Valley, says: “In March 2000 we were less than a year old, but had two US companies offering $200-$300m (£138-£208m) for the business. It felt like a drug-induced euphoria. But the drug in this case was Nasdaq. There was a complete absence of methodology. It felt like the valuations would go up no matter what you did. It was not even about generating revenues. All you needed was to show growth.” Unlike many of the pioneers – such as Netscape, which had shaken up the way consumers browsed the internet – they did not even need to write their own computer code. “It was a whole bunch of get-rich-quick artists,” complains Mike Moritz, the venture capitalist at Sequoia Capital who had given the founders of Yahoo!, the internet portal, their first million. Perry Blacher, a venture capitalist at Chase Episode One in the UK, says: “There were fewer technology people in Europe. In the US, you had people hanging around waiting to turn ideas into a business. While in Europe, you had more people coming out of business school thinking it was easy to create businesses.” No ideas? Nick one from Nasdaq Many of these consultants looked for inspiration from Nasdaq, creating copycat rivals of companies that had attained successful flotations. “There was a lemming-like rush to copy anything from the US. People looked at businesses in registration with the SEC [the Securities and Exchange Commission in the US] and then copied it and sent the plan to European venture capitalists. Within a month you would see business plans with large sections plagiarised from the filing documents,” says Mr Zwillenberg of KPE. For a time in early 2000, the emergence of a new, aggressive internet generation spooked old-economy magnates. “ You constantly heard with major corporations, ‘We don’t want to be Amazoned’, and you heard from venture capitalists and entrepreneurs, ‘How can we be the Amazon of our space?’,” said Arthur Sculley, a former European corporate financier who is now an investor in internet companies. The potential threat from dotcoms was felt keenly by traditional companies in Europe, which had been able to witness from afar the ability of start-ups such as Amazon to emerge from nowhere and establish themselves as leading internet e-tailers. European companies reacted faster to this threat, many announcing plans for aggressive internet investments to ensure no loss of market share – and mindshare – to the startups. Retailers such as Fnac and Redoute of France, and Tesco and Argos of the UK, were among the first to shift their brands online and spend in order to stay ahead of the start-ups. The strain was also beginning to tell in the financial system. Until the internet, technology investing in particular was an acquired taste, according to Dhiren Shah, who handles technology IPOs and mergers and acquisitions for Morgan Stanley Dean Witter in New York. “Technology investing was a pretty arcane thing. There were few investors dedicated to it. Tech IPOs were pretty tiny and the IPO window opened and shut all the time,” he says.The public hunger for internet investments blew that window wide open and produced an imbalance between the supply of companies – particularly companies with strong prospects – and demand for dotcom stock. That was especially true in Europe. By March 1999, just 20 internet companies had come to the market in Europe, according to Miles Saltiel, an internet analyst at WestLB Panmure. Over the next 18 months, more than 150 companies floated, he says. © Marketing Insights Ltd 2004 The lack of internet companies mature enough to make it to the public markets created an opportunity for proxy internet companies to float. For example, 365.com, a UK company, presented itself to the stock market as an internet company – even though less than 9 per cent of its revenues came from the internet. The bulk of 365’s revenues at the time derived from premium-rate chatlines, such as dating services. Immature European market Demand for internet stocks was also met by the flotation of early-stage internet investment companies. Blakes Clothing, a struggling menswear retailer, managed to reinvent itself as an internet fund – its shares rose 18-fold, giving a company with assets of just £3m (€4.7m) a valuation of £220m (€345m). In the UK, dozens of companies – some calling themselves incubators or internet accelerators – were able to attain extraordinary valuations for a short period of time. Investors who bought shares in these vehicles were effectively paying a premium for a pile of cash. Victor Basta, managing director of Broadview, a technology investment bank, says these funds were in stark contrast to US equivalents and reflected the immaturity of the European market. “What you have here is an increase in value from day one, based on absolutely no delivered performance.” Recruitment frenzy Appetite for internet stocks – no matter how flaky – was so high that investment banks struggled to bolster staff levels for the internet stock boom, while at the same time reaping rich fees from initial public offerings. Internet analysts were also in short supply.” They gave responsibility to people who knew nothing,” says Miles Saltiel of WestLB Panmure in London. “Often the reports were just hundreds of pages of IDC [International Data Corporation, a research company] charts, showing that everything was going to get bigger and bigger next year. They provided little analysis, but were brick-like calling cards for the next IPO.” “I can think of one [bank] that moved 14 people into their investment banking group for internet companies [in 1999],” says Mr Sculley. “They didn’t have much experience in that sector; they did have experience of underwriting and knew how to ask the right questions. Did they have any experience of the internet? No, but quite frankly, nobody had that kind of experience two years ago, so everybody was learning on the fly.” By the end of 2000, the SEC had opened an inquiry into the methods by which investment banks had allocated shares in the hottest IPOs. In Europe, too, the consequences of the decision to ease the listing criteria on some public markets, such as allowing companies without a three-year trading record to float, are starting to be felt. For example, Letsbuyit.com, a pan-European internet retailer, was forced into filing for bankruptcy less than nine months after it first came to the Neuer Markt (although it is now back in business). Other internet companies have admitted accounting irregularities – a consequence of poor management, and the desire to meet over-hyped growth expectations. But at the time, concerns about the sustainability of some internet companies did not matter. Instead, stories of enormous personal wealth were generating a feeling that almost anybody could become a millionaire – or, at least, make money from investing in stocks headed by instant millionaires. Interviewed last summer, Glen Meakem, chief executive of Freemarkets, a US online auction site for businesses, recalled how “in the bubble of last winter there was tremendous jealousy... There were a lot of guys like me who were worth $1bn [£693m]”. Even after the stock market bubble burst, the personal wealth created by the internet for some individuals remains astounding by any traditional yardstick. Mr Meakem was worth $1.35bn (£935m) on paper when Freemarkets’ stock peaked – a figure that had dropped to $200m (£138m) by last summer. “I like to kid [to my wife] that Barings lost $1bn and it brought down the bank. We lost $1bn and we still kept the family together,” he said. As a result, in the first quarter of 2000, cash flooded into the mutual fund industry. © Marketing Insights Ltd 2004 “ You’d see one or two funds have good performances, then 19 or 20 copycats would come out,” says Chris Trawlson, an analyst at Morningstar, the mutual fund research group. Rival Lipper reckoned that more than a third of the technology funds it lists in the US were created between October 1999 and October 2000, most of them just in time for the spring stock market bust. Desperate to avoid missing out, fund managers skimped on due diligence, the financial analysis they usually carried out to ensure that they were investing pension funds’ and individuals’ money sensibly. Walter Price, co-manager of the Dresdner RCM Global Technology Fund, recalled last year how his fund bought into Webvan, the online retailer, at its roadshow in the summer of 1999. “You had to buy it, you didn’t have time to do your research. In those roadshows, you’re just separating the real companies from the not-real companies.” Only after buying the shares did Mr Price’s fund have a chance to delve more deeply into Webvan’s business. Its conclusion: the prices the company charged for groceries were not as competitive as they had appeared initially. Just four weeks after the IPO, the Dresdner fund changed tack and sold its shares. “A company like that would never have been able to get funding before,” concedes Kevin Harvey, a partner at Benchmark Capital, which was the first Silicon Valley venture capitalist to back Webvan. Interviewed a year after the IPO, George Shaheen, who traded his job at the consultancy firm Accenture (formerly Andersen Consulting) to run Webvan, said: “That time was an anomaly There was an unbridled optimism that any internet company would be valued highly. There was unlimited upside.” By the end of 2000, Webvan’s shares were trading at less than 50 cents (35p). Reversal of fortune EToys, the online toy retailer, was another company that saw the high hopes of 1999 evaporate last year. Its shares had more than trebled on its first day of trading in May 1999, reaching a peak of $86 (£59.60) towards the end of 1999. In spite of heavy advertising, and praise for everything from website design to efficient order fulfilment, its shares had fallen to below $5 (£3.50) by the autumn of last year. Just before Christmas, eToys warned that fourth-quarter revenues would be half previous expectations and that it had hired an investment bank to explore its options. Many of Europe’s highest-profile internet stocks – both public and private – have also suffered a sudden change in fortunes. One was QXL, the European equivalent of eBay, the auction site. Led by Jim Rose, an ebullient American, the company bought into the prevailing stock market mantra of 1999 and early 2000 – to exploit first-mover advantage and become panEuropean as fast as possible. It appeared to be paying off when a young analyst, Thomas Bock of SG Cowen, rated them a strong buy and set an aggressive 24-month price target of £44 (€69). He justified the move on the basis that no one had expected eBay to become a $25bn (£17.3bn) company. The note pushed the stock up 128 per cent on the day. But that high-water mark did not last long. Concerns soon mounted that QXL had overreached itself in gobbling up Bidlet, a Scandinavian rival, and Ricardo.de in a matter of months. Attention shifted to its ability to integrate these acquisitions, and to its hefty burn rate. Letsbuyit.com has been another casualty. Even before it floated in July 2000, the warning signs had been clear. Goldman Sachs, the investment bank which had been appointed to help float the company on the Neuer Markt, had doubts about its potential valuation and pulled out. In the end the company had to slash its offer price several times before it could successfully float, raising $62m (£43m), on top of the $120m (£83m) it had raised pre-IPO. The shares never really recovered from the rocky flotation of Letsbuyit.com and were dragged down by the pummelling of business-to-consumer stocks. In January this year the company was forced into bankruptcy proceedings, when its cash had dwindled to just $17m (£11.8m). As dotcom entrepreneurs began to fall by the wayside, they glimpsed the dark side of the same world of banking that had given them the funding for their companies. Bill O’Connor, the creditors’ rights lawyer, recalls a typical loan workout session for a dotcom: “They come in quivering; they have been used to jolly, friendly bankers and jolly, friendly lawyers and now they are sitting in a room with a bunch of guys in white shirts and ties, who are asking them in effect to empty their pockets, give them their Rolex watches and sports cars, and turn over the lease.” © Marketing Insights Ltd 2004 Operating between the old and new economies The downturn has taken its toll on more experienced managers too, attracted from established companies to dotcoms by little more than the promise of stock options and the excitement of working for a small start-up. Heidi Miller jumped from being chief financial officer of Citigroup, one of the largest financial services companies in the world, to Priceline, the name-your-price website, in February 2000, but resigned in November. Earlier this year she was named vice-chairman of Marsh, the insurance broker. Joe Galli first joined Amazon.com then VerticalNet, which operates business-to-business websites, after leaving Black & Decker, the toolmaker. He switched horses again in January, but this time he became chief executive of Newell Rubbermaid, the distinctly old-economy manufacturer of Rolodexes storage products and cookware. But the return of Mr Galli and Ms Miller is not so much a signal that the thrill has gone out of the internet in the US as that corporate America has caught up with the dotcom upstarts that blazed a trail. As Mr Galli put it, shortly after joining Newell Rubbermaid: “I want to take this traditional company and operate right between the new economy and the old economy.” Concerns that the wave of entrepreneurialism in Europe would be damaged by the collapse of so many internet start-ups so quickly have also proved unfounded. The founders of ClickMango, a UK-based health products e-tailer, for example, remain committed to the internet, in spite of the collapse of their company after its investors pulled out. Toby Rowland, one of the founders interviewed after the collapse, says: “We felt we wanted to take on more responsibility and take bigger risks. The internet allowed people to change careers without having to go to business school.” Robert Norton, ClickMango’s co-founder, confirms: “Toby and I have no intention of returning to our old jobs. Being outside the corporate environment is liberating.” Even after witnessing the financial turmoil of 2000, many internet pioneers remain optimistic about the prospects for the world-changing technology which they had a hand in creating and promoting. The fact that it is now being put to unglamorous uses such as supply chain management, rather than being used to overturn the institutions of the old economy, might just be the dotcom rebels’ most durable legacy. Email Andrew Hill and Caroline Daniel at andrew.hill@ft.com caroline.daniel@ft.com Question Read the article and using the analysis in the article and your own analysis list reasons why many Internet startup companies failed. © Marketing Insights Ltd 2004