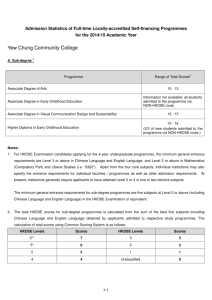

Organisation of sub

advertisement