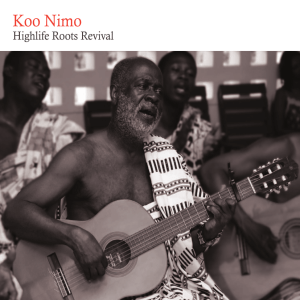

GHANA SPECIAL Soundway documents Ghanaian

advertisement

Photo courtesy of Forced Exposure Records. GHANA SPECIAL Soundway documents Ghanaian highlife’s roots “By 1957, my guitar solos were being whistled around the country,” Ebo Taylor boasts as he reminisces on his successes during the early years of highlife. It’s true, by the time he was twenty years old, Taylor could already be considered a seasoned highlife guitarist. No doubt growing up in Cape Coast gave him an edge; coastal Ghanaian musicians drew from a rich lineage of palm-wine guitar, a distinct blues-like folk music that gets its name from the special palm beverage often served at musical gatherings. But Taylor’s talents were exceptional. By 1957—the year Ghana gained its independence from British colonial rule—he had already toured the country’s dance-band circuit, an honor usually afforded to only the most affluent Ghanaians or the most talented and seasoned musicians. Taylor’s guitar playing also earned him a spot touring West Africa with the Havana Dance Band, making him a regional star. Much to his parents’ dismay—they hoped he’d become something respectable like a doctor—Taylor knew he was a good guitar player and chose musicianship as a career. His talent rose to symbolic ranks because of his country’s historical timeline. Ghana was navigating the hazards of sovereignty, its people struggling with their new identity—trying to reconcile the vestiges of colonialism with its responsibilities as the shining star of West African freedom—and highlife music became an important symbol of cultural unity. Highlife, a special brew with equal parts big-band jazz horns, Ghanaian palm-wine guitar riffs, Caribbean calypso rhythms, and traditional African percussion, represented Ghana’s heritage. Music’s significant cultural role during the uncertain years of Ghana’s youth was not lost on Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, who sent Taylor and many other gifted Ghanaian musicians to London music schools on prestigious national scholarships. “It was in London that I learned more about arrangement and composition, and I was exposed to American arrangers like Duke Ellington and Glenn Miller,” Taylor explains. His years at London’s Eric Gilder School of Music 32 would refine his talents and transform him into a skilled musician, writer, and composer. Taylor is one of many prolific highlife musicians featured on Soundway Records’ latest release, Ghana Special: Modern Highlife, Afro-Sounds, and Ghanaian Blues 1968–81, which delivers thirty-three gems from Ghanaian highlife’s golden years. It was during this period that both Taylor’s career and highlife music took shape. Returning from London in 1968, Taylor quickly became one of the most influential musicians on the highlife scene. He immediately reformed his old crew, the Broadway Band (whose later incarnation, Uhuru Dance Band, is featured on this release), hipping them to the jazzstyled instrumentations that he picked up while abroad. His writing and composing skills landed him a gig as in-house arranger and A&R for one of Ghana’s largest independent labels, Essiebons Enterprises, where he created hits for himself and other highlife legends. Taylor’s work in the ’70s helped shape the modern highlife sound. His four solo LPs featured classic highlife arrangements on the A-side and more modern sounding, Afro-fusion tracks on the flip. “Back then, adding new elements in our music was exciting,” he says. “I wanted to push things.” Taylor’s modern classics like “Twer Nyame” kept traditional highlife instrumentation—crisp, big-band-style horn arrangements with grooving percussion—but added fresh, modern elements like electric keyboards and guitars, reinventing the highlife sound for a new generation. These days, Taylor and highlife music have a rightful place at the University of Ghana, under the tree in the main court of the music department where Taylor teaches Ghana’s next generation of musicians their basics in palm-wine and highlife guitar: “Minor chords, it’s all about your minor chords.” Always boasting, he teaches through story and by example. “My solos were outstanding,” he says. “People called for me when the band would come and play. Now pay attention to this solo.” . Kristofer Ríos