A Case Study of Highlife Music

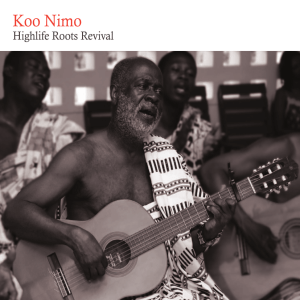

advertisement

The Concept of Change and Genre Development: A Case Study of Highlife Music By Austin Emielu Ph.D. Department of the Performing Arts, University of Ilorin, P.M.B. 1515 Ilorin, Nigeria A paper presented at the First International Conference on Analytical Approaches to World Music, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, U.S.A. Feb. 19-21, 2010. Introduction Highlife music developed in the West African sub-region in the late 19th and early 20th centuries from a fusion of three major elements namely: indigenous African music, European and New World music from America and the West Indies (Collin, 2005:4). Because of its diverse parentage and the ethnic and cultural diversities of the West African sub-region where it gained ascendancy as its most popular music genre through the 1950s and 60s, the stylistic framework of Highlife music is not uniform. Coupled with generational modifications arising from the socio-technological changes of the 21st century, the issue of what constitutes the ‘original’ Highlife and its definitive and stylistic framework in contemporary times, has been an unresolved one among practitioners and patrons across generational groups and regions. This has led to several ‘revival’ concerts since the 1980s in a bid to bring back the ‘good old Highlife’, regarding new developments as bastardization or mutations of the ‘original’. Data for this paper were gathered mainly during my research on Highlife music in the West African sub-region between 2005 and 2008. Specifically in Nigeria and in Ghana, the issues of what constitutes Highlife music and the rules of inclusion and exclusion continuously confronted me. Coupled with my experience as a studio musician, producer and band leader working with various musicians and bands in the West African sub-region since the 1980s, I strongly felt the need to develop analytical and theoretical models with which to analyze African popular music, especially against the backdrop of increasing social and technological changes of the 21st century. In doing this, I adapted three developmental change models from business management perspective and deployed them in the analysis of developmental trends and categorization of the products of these changes. To further concretize these analytical approaches, I then developed some new analytical models and approaches of my own based on my theory of social reconstructionism in which I posited that a socially constructed musical phenomenon can be socially deconstructed and socially reconstructed contingent on prevailing sociomusical and historical processes. Furthermore, I stressed that African popular music like the African man, never dies but passes through cycles of transformational changes and 2 genre development which ensures it sustainability along a historical and generational path. The Development of Highlife Music In specific terms Highlife music developed from a fusion of regimental brass band music of the West African military and Frontier Forces and colonial administration; Jazz, Swing and other forms of popular music from America; Calypso, Samba Cha Cha Cha, Foxtrot, Meringue from the Caribbean and the West Indies; guitar music of Liberian Kru sailors, music of returning ex-slaves and ex-service men as well as the social recreational music of tribal groups in the West African sub-region. Highlife music first grew as a sub-regional music in the then British West Africa before its articulation in specific West African nations, especially Ghana and Nigeria as an ethnonational socio-musical phenomenon (Emielu, 2009). The primordial roots of Highlife are located in a diversity of social recreational music of the West African peoples. Some of these indigenous musical forms include Adaha, Kokomba and Osibisaaba in Ghana (Collin, 1992, 2004); Egwu Ekpiri, Ogene, Itembe and Ekombi in Eastern Nigeria1; Akwete and Ekassa in Midwestern Nigeria (Obidike, 1994); Dundun, Apala and Sekere music in Western Nigeria (Euba, 1975), Swange and Kalangu music in Northern Nigeria (Ajirere, 1992). These indigenous musical forms were fused with a multiplicity of foreign musical influences as mentioned before. As early as the late 19th century, proto-Highlife forms such as coastal Fanti Adaha brass band and maritime-influenced Osibisaaba guitar music began to emerge in Ghana. The Fanti coast had one of the earliest contacts with Europeans. As early as about 1482, the Fort Elmina was built by the Portuguese in this area. The presence of indigenous dance music before European contact as well as the influence of European dance music and Ballads, Calypso and Rhumba brought by returnee ex-slaves from Brazil helped to consolidate the growth of dance band music in this area (Omojola, 1995:23). By about 1925, the word Highlife was coined in the context of elite dance orchestras which sometimes played African tunes using Western orchestration. In Nigeria, brass band music of military and regimental bands stationed in West Africa during the World War periods inspired the formation of African Brass band groups like the Effiom Brass Band and the Niger Coast Constabulary Band in Calabar; 3 the Bakana Brass Band in Rivers state; the New Bethel School Brass Band and the Ikot Ekam Brass Band in Cross Rivers State. (Akpabot,1986:4). During the missionary/colonial era, most elementary and secondary schools had military-typed marching bands used for morning assembly. The British Empire day (May 24th) celebration was also a great occasion for school bands to display dexterity on brass instruments. Many ‘graduates’ of these school brass bands later became important Highlife musicians both in Ghana and in Nigeria. Another major root of Highlife is found in church hymns introduced by Christian missionaries in West Africa. The arrival of various church missions in the middle and late nineteenth century, each with its own set of hymn tunes helped to popularize hymn singing. Church hymns with their penchant for primary and secondary chords as harmonic devices, as well as parallel vocal harmonies, provided the harmonic basis for Highlife tunes and orchestration and attests to the importance of the church in the development of Highlife as a musical genre both in Ghana and in Nigeria. This attestation lends further credence to Rhodes’s (1998:6) submission that the musical background of E.T. Mensah who introduced the dance band Highlife incarnation was influenced by Methodist Church hymnal style and that Mensah’s Highlife tunes followed a hymn meter. Within the West African sub-region also, the influence of Liberian Kru maritime workers is quite significant in the development of Highlife. These Kru sailors had worked abroad on European sailing ships since the period of the Napoleonic wars in Europe. As sailors, they carried around portable musical instruments like the concertina, banjo, harmonica and most significantly, the acoustic guitar. They introduced the twofinger guitar playing style which alternates the thumb with the index finger in a kind of cross-rhythm. It is on record that a Kru in the 1920s, taught Kwame Asare (also known as Jacob Sam), who is Ghana’s pioneer Highlife guitarist, the two-finger guitar style. Kwame Asare and his Kumasi Trio recorded one of the earliest Highlife songs for Zonophone records in London in 1928 (Collin, 2005:5). One of the hit songs on this recording was Yamponsah, a name which has become synonymous with the two-finger guitar style popular both in Ghana and in Nigeria. 4 The roots of Highlife music lies therefore, in the social dance music of several cultures in the West African sub-region before European contact, as well as early syncretic musical forms such as Gumbey music in Sierra Leone, Adaha Kokomba or Kokoma in Ghana and Nigeria, Asiko and Itembe music in Eastern Nigeria and Agidigbo music in Western Nigeria. These forms which usually combined traditional instruments with Western musical instruments like the acoustic guitar, banjo, accordion and harmonica were subsumed under an amorphous label of ‘palm wine’ music because of their predominance in palm wine (or tombo in local parlance) bars during their hey days. They also bear the double toga of being part of the developmental processes in the crystallization of the Highlife form and as well representing what can be described as a ‘poor man’s’ version of Highlife music. These various palm wine styles went into the tapestry of what later became known by the generic name of Highlife. Consequently, this subtlety of interaction between European/American and ethnic-based recreational music translated into ethnic and regional styles of Highlife music which necessarily exist within a stylistic and sociological framework of what may be termed as ‘Nigerian’ or Ghanaian ‘Highlife’ and their ethnic variations. By around 1950, recognizable stylistic patterns of Highlife music had emerged in Nigeria and Ghana. This was most significantly through the music and performance tours of Emmanuel Tettey Mensah (E.T. Mensah) and the Tempos band of Ghana, who toured the West African region extensively from the 1950s. Although Mensah helped to spread Highlife music through his West African tours, it was in Nigeria the country he visited most that Highlife music caught on most significantly outside its home base in Ghana. Mensah is generally believed to have bequeathed to Nigeria, the dance band Highlife incarnation so recognized today (see Rhodes, 1998:6 Aig-Imokhuede 1975:214215 and Collin, 1992:24-25) . In his own reaction to the claim that he is the originator of Highlife, E.T Mensah humbly submits that no one can really lay claim to Highlife’s creation because it has always been there entrenched in West African culture and that what he did, was to give Highlife world acceptance (Mensah, in Okwechime, 1984:13). While it is plausible that the nomenclature Highlife, predates E.T. Mensah and the Tempos Band of Ghana, E.T. Mensah is the man who pioneered the dance band format as a contradistinction to the big 5 band orchestras of the inter-war period which spread as far as Nigeria. This dance band format is generally regarded core of the Highlife genre because of its wide geographical spread and popularity. Consequent upon this, by the mid-1950s and 1960s Highlife practitioners and their patrons could have developed a mental template of the definitive framework of what constitutes Highlife music both in Ghana and in Nigeria. This mental template may be thought of as socially negotiated among the various social groups like the musicians who played the music, patrons who consumed the product, recording and marketing companies who promoted it and critics opposed to the music at that point in history . This is a central concept of social constructionsim, a sociological theory which perceives social reality as highly contingent upon social and historical processes. Yet, in contemporary times there have been increasing debates and disagreements over what constitutes the ‘original’ Highlife and its contemporary modes of expression. This has led to a clamor for the revival of the ‘old tradition’ of Highlife especially in Western Nigeria. However, while some practitioners and their patrons feel that Highlife music is going into extinction, others feel that the music is still very much around but in different guises (see Aig-Imokhuede 1975:215, Ajirere (1992: 90) and Ọmọjọla (2006:122)) . It is against this backdrop that we attempt a classification of Nigerian and Ghanaian Highlife later on in this paper to determine the limits of Highlife’s generic boundaries amongst other things. While the history of Highlife music is not the main focus of this paper, it is important to identify some significant phases in its historical development. This is to provide a conceptual and comparative framework for our analysis of socio-musical changes and genre development. This explains my choice of representing historical details graphically below. Development of Highlife Music in Ghana Period Major Features Musical Configuration Late 19th Cent -1920s Early European contact around the Fanti Coast 19301939 Spread and indigenization /vernacularization of early Early syncretic forms: Fanti Adaha brass band and Osibisaaba guitar music. Syncretization of the foreign and the local Transformation of Adaha and Osibisaaba. Genre Development Coinage of the word Highlife in the context of elite dance orchestras in about 1925 Emergence of Kokoma, Odonson 6 19391946 syncretic forms as far as Nigeria. Impact of second world war. 19461957 Period of nationalism and independence. Nkrumah’s open support for Highlife. Highlife spread to Nigeria. Visit of Louis Armstrong. 1960 1970 Arrival of pop music, Soul, Twist and Rock’n’Roll. 19701980s Period of political instability and economic hardship. Exodus of many Ghanaians abroad. Decline in live music. Mobile discos. Age of techno-pop. Introduction of digital drum machines and programmed keyboard music. Revival of Classical Highlife Age of American Hip pop music; return to civil rule and liberalization of the economy. Return of Ghanaians from abroad. 1990s Circa 2000 present Introduction of Swing, Calypso and AfroCuban music. Fusion of Highlife and Concert party. Introduction of Jazz melodic and harmonic progressions into Highlife Fusion of new music with Highlife and neotraditional Kpanlogo music. Cross-fertilization of Nigerian and Ghanaian Highlife. Introduction of Christian themes. and Palm wine music as prototypes. New musical resources imputed into Highlife. Dance band (classical) Highlife emerges through E.T. Mensah. Rise of guitar Highlife. Creation of Afrorock and Afro-beat from Highlife. Highpoint of Highlife development. The gradual emergence of Gospel Highlife and predominance of female musicians The fusion of Highlife and techno-driven pop music. Creation of ‘Burger’ Highlife by Ghanaian musicians in Germany. Fusion of American Hip pop and Highlife. Emergence of ‘Hip Life’ as Contemporary Highlife alongside classical format Development of Highlife Music in Nigeria Period PreIndependence 1950-1960 Major Features Musical Configuration Genre Development Age of nationalism Cross-cultural musical The birth of Dance and cultural revivalism perspectives from band (Classical) towards self-rule and Europe, America and Highlife through independence . indigenous African E.T. Mensah and the music. Tempos Band of 7 PostIndependence 1960-1970 Post-Civil War Period 1970-1980 Economic Depression Period 19801990 Last Decade of the 20th 1990-1999 The 21st 1st decade of independence and the Nigerian civil war of 1966-1970. The growth of hotel-based bands. Displacement and relocation of Igbo Highlife musicians from the Western to the Eastern region. Oil boom and the ascendancy of Juju music in Western Nigeria. Gradual return of Igbo Highlife musicians to the Western region. Triangular sociomusical relationship between bands and musicians in Nigeria, Ghana and the United Kingdom. The introduction of Jazz harmonic progressions into Highlife. Juju-Highlife interface and cross-overs. Interface of Ghanaian and Igbo Highlife; Increased use of traditional musical instruments in Highlife music and a synthesis of Highlife with Congo guitar styles, Soukous and Makossa. Government Structural Beginning of solo Adjustment program; artiste syndrome in Gradual devaluation of Nigerian music and the the Naira, import emergence of youth pop restrictions and social stars. Decline in Hotelinsecurity. Mass based Highlife music deportation of and musicians. Ghanaians including Introduction of drum musicians. machines and programmed keyboard music. Lesser emphasis on brass instruments March towards Ascendancy of Fuji democracy. Corporate music in the West; sponsorship of musical gradual interface of concerts and Pop and Highlife musicians; Highlife revival projects in Lagos. Age of ICT, global Combines elements of Ghana. The Highlife genre was transnational in outlook. Short track Highlife format. Development of Highlife music along ethnic and regional lines. The development of Jazz-Highlife as a sub-genre of Highlife. Development of Afro Beat from Highlife; development of Juju-Highlife in the West and guitar band Highlife in Eastern and Midwestern Nigeria. Long Play (LP) Highlife format. Consolidation of Igbo guitar Highlife and gospel Highlife in the West; Keyboard-driven Highlife and solo acts. Incorporation of praise singing into Highlife. The birth of Contemporary Highlife Re-emergence of 8 Century spread of digital music and technology; ease of travels and communication. the old and the new; pastiche base of various genres; amorphous definitive framework. ‘old school’ ‘classical’ Highlife alongside Contemporary forms. Highlife as a Musical Genre While some scholars have alluded to Highlife as a stylistic format with a definitive framework, others see the nomenclature as a generic name for a wide range of styles arising from the musical acculturation between Africa and Europe (see Omojola, 1995:21, Collins 1992: and Ogisi 2004:38). In a sense therefore, reference to Highlife music as a generic label for a wide range of syncretic dance music in West Africa is understandable considering Highlife’s diverse roots and modes of expression in each culture. Although Highlife music has been widely discussed among practitioners, patrons and scholars, no one has been able to provide a working definition of what Highlife music is or is not. The nearest definition or conception that we have is that Highlife is a musical genre that combines traditional and Western musical resources. This definition is not only amorphous, but also symptomatic of African popular music generally. This is why it is important to interrogate some theoretical perspectives on the generic classification of creative works which are rooted in genre theories. By way of simplistic clarification, genre theory deals with the ways in which a creative work may be considered as belonging to a class of related works based on distinctive qualities and peculiarities. In literature, drama and media studies, genre functions to categorize creative works into such compartments as comedy, satire, tragedy, tragi-comedy, war films and so on. Van der Merwe (1989:3) defines a music genre as a category of pieces of music that share a certain style or basic musical language. In this sense, Highlife can be recognized as a musical genre. One group of genre theorists however, do not see the need for genre classification because of inherent definitional problems. Among them is film theorist Stam who questions: 9 Are genres really out there in the world, or are they merely constructions of analysts? Is there a finite taxonomy of genres or are genres timeless platonic essences or ephemeral, time-bound entities? Are genres culture-bound or trans-cultural? Should genre analysis be proscriptive or definitive? (Stam 2004:14) Supporting Stam’s position above, Feuer (1992:144) submits that “ a genre is ultimately an abstract conception rather than something that exists empirically in the world”. Chandler (1997) also sees genre classification as a ‘theoretical minefield’, while Neale (1995:464) argues that “Genres are historically relative and therefore historically specific”. Going by Neale’s submission above, frequent references by practitioners and patrons of Highlife music to ‘the good old days’ of Highlife, may suggest that Highlife music is a product of a historical past. When viewed from this perspective, revival projects of E.T. Mensah of Ghana and Nigeria’s Victor Olaiya in 1983 in Lagos, the BAPMAF/Goethe Institut ‘Highlife Month’ held in Accra in February 1996, the Goethe Institut ‘Highlife Party’ held in Lagos in 1998 and 1999 and the current monthly Highlife ‘Elders’ Forum’ at the Ojez Nightclub in Lagos, may just represent at best, revivals of a fading tradition. Yet, there are contemporary modes of Highlife expressions as seen in the music of Chris Hanen of Ozigizaga fame, Bright Chimezie, Sunny Ineji, Lagbaja, Jesse King’s and many others in Nigeria; the ‘Burger’ and ‘Hip Life’ styles of C.K. Mann, Daddy Lumba, Nana Kyeame, Batman Samini and several other musicians and bands playing similar styles in Ghana. But whether old musicians and patrons of Nigerian and Ghanaian Highlife music accept these contemporary modes as belonging to the Highlife category is another issue. For example, while watching a live performance of contemporary Nigerian musician, Sunny Ineji in Abuja Nigeria, the late veteran of Highlife, Chief Osita Osadebe commented: “ they want to convert Highlife and play it as pop music but it will never work. Highlife is Highlife” 2 Osadebe’s comment and position highlights the growing generational gap between ‘old’ and ‘new’ Nigerian/Ghanaian musicians. This is why it is important to adopt a historical and contemporary approach in the study of Highlife music both in Ghana and Nigeria. However, as Miller has rightly observed, “ the number of genres in any society depends on the complexity and diversity of that society” (Miller, 1984). Thus the ethnic 10 complexity and cultural diversity of the West African sub-region must be taken into account in our classification of musical genres and in determining the rules of inclusion in and exclusion from the Highlife category. This is why Gledhill (1985:64) submits that “ genres are not discrete systems consisting of a fixed number of listable items”, while Neale (1980:48) is of the opinion that “genres are instances of repetition and difference”. Despite inherent problems in genre classification some of which have been discussed above, it is necessary to still classify creative works according to certain criteria so that genres do not exist as formless and amorphous entities which will preclude interpretation and analysis. The Concept of Change and Genre Development Change as a concept has been defined by Jick & Peiperl (2003:xvi) as a “planned or unplanned response to pressures and forces and I agree with him largely. The global ‘soundscape’ of the 21st century with its avalanche of economic, technological, musical, social, political and ideological changes have created several layers of pressures, choices and survival strategies. From the graphic historical development of Highlife music earlier on, we can see that the development of the Highlife genre has been characterized by changes which define the genre in specific social and musical terms synchronically and contextually. We are also able to understand to some extent, the dynamics of musical change and responses to such changes in contemporary Africa. However, to manage these changes and put them in proper theoretical perspectives, I will deploy three perspectives of change developed by Linda Ackerman3, a business management expert. The models will help us to analyze these changes and to also assess how best they can serve as analytical tools for musical change and genre development. Fig. 1a Developmental Change Involves continuous improvement of what is 11 The model above involves the continuous improvement of a skill, method or condition which do not meet current expectations. In this case, continuous changes along an upward path will lead to greater improvement, development and sustenance. Sustenance is therefore, directly related to progressive and continuous developmental changes along an upward path of evolution. It is a linear model of change. In terms of Highlife music, this will mean periodic introduction of new innovations that represent positive changes in the Highlife style, strong enough to sustain audience interest on a continual basis. This seems to support Benson Idonije’s (one of the greatest champions of the Highlife revival projects in Nigeria) view that Highlife is not thriving as a musical idiom because over the years, it has failed to experience any form of artistic development and innovations (Idonije, 2001:29-30). This presupposes that the Highlife genre has been in a state of inertia but this is not so. However, the developmental change model does not acknowledge the social processes of change and the adjustment to such changes, which could lead to the development of multiple and alternative patterns of life, tastes and choices. The resultant effect is that continuous improvement of a product does not actually guarantee continued usage and patronage, due to some sociological and psychological factors that affect consumer behavior. To me, the greatest strength of this model is that there is an established starting point against which other forms of developmental changes can be measured. Fig.1b : Transitional Change old State Transitional State New State of product Involves the emergence of a known new state and the management of the interim transitional state over a period of time. This is a typical case of changing from the ‘old’ to the ‘new’. What is not clear in the model is whether the new product is different from the ‘old’ both in composition and 12 nomenclature. However, the transitional state represent a stage of ‘deconstruction’ of the old product and the gradual emergence of a new product with presumably, some elements of the old product. Although it is not specifically stated in the model, it is logical to think that the process is a circular one. This is because the new product becomes sooner or later an old product, and the process of change begins again. The idea of deconstruction as typified by the transitional stage and the emergence of a new state are strong points in this model. Although the issue of deconstruction will be discussed later in this paper, I wish to emphasize that many musical forms have emerged from Highlife, though not necessarily acknowledged by the practitioners of such genres. For example, Victor Uwaifo’s Akwete, Sassakosa, Mutaba and Titibiti sounds which are derived from his Edo culture in the old Midwestern region, are musical changes which may or may not be classified as Highlife (Emielu, 2009). The development of Afro Beat and Juju music from Highlife are all so cases in point. Fig. 1c Transformational Change Plateau or peak of development decline Re emergence or revival Birth (Adapted Death Source: Linda Ackerman Inc © 1984 Fig 1c captures in totality, the current thinking and social perception of stagnation and decline of Highlife music in Nigeria and the need for its revival which has been on since the 1980s. The model above seems to suggest a typical economic product cycle which is characterized by birth, growth and maturity, decline, ‘death’ and ‘rebirth’. In 13 Nigeria, this model can fit into the mindset that Highlife was born in the 1920s and 40s from its ‘palm wine’ origins and big band orchestras, reached the peak of its development in the 1950s and 1960s, stagnated around the late 1960s and began eventually to decline somewhere around the late 1970s, while the 1990s represent a period for its revival and re-emergence. This perception of absolute decline is at the centre of the various Highlife revival projects in Lagos currently. However, rather than transformational changes, what is sought in these revival projects seems to be a revival of the ‘old’ tradition of Highlife. How realistic and possible this is under the prevailing social, economic and technological changes of the 21st century is a crucial issue in this research. Understanding transformational changes is important in tracing the development of a musical genre over time. Some Observations and Deductions From my research, I observed that Highlife music exists in diverse forms which reflect the diverse roots of Highlife music and the ethnic diversity of the West African region. Based on principal and identifiable elements, the following forms of Highlife music were identified in my research: (a) Secular Highlife: Uses secular themes as opposed to Christian or religious themes. (b) Gospel Highlife: Uses Christian or religious themes as opposed to secular themes. (c) Classical Highlife: A Highlife style which many old musicians call the ‘original Highlife’. It uses mainly 4/4 meter and combines a range of brass instruments, trap drum and other local percussions especially the conga drum with the guitar in a moderate elegant tempo. It is most times referred to as ‘old school’ Highlife by the new generation. (d) Folk Highlife: Highlife based on folk songs of ethnic groups. No claim to authorship except in the re-interpretation and re-arrangement of such songs by individual musicians. (e) Brass Band Highlife: Consists of essentially brass instruments which may or may not be combined with guitar and percussions. (f) Guitar Highlife: Consists essentially of guitar and percussion instruments. This could be acoustic ‘unplugged’ or electric ‘plugged’ guitar. Guitar Highlife has its roots in ‘palm wine’ and Congolese music. Multiple guitars are sometimes 14 used to add to the harmonic density of the music. Brass instruments are deemphasized (g) Contemporary Highlife: Refers to a wide range of new developments in Highlife music of in the new millennium. The definitive framework of contemporary Highlife is not only amorphous, it is also a site of struggle and a point dispute between traditionalism and contemporariness and between essentialism and social constructionism. It has a pastiche or hybrid base that combines historical styles with new innovations in contemporary music. Digital and synthetic sound is emphasized over and above the analog sound of ‘classical’ Highlife. The sound relies more on programmed computers and electronic keyboard instruments. Jesse Jackson’s Buga style, Sunny Ineji’s pop-styled Highlife in Nigeria and the‘ Burger Highlife’ and Hip Life in Ghana are concrete examples of Contemporary Highlife. (h) Juju–Highlife: This categorization represents a new synthesis of Juju and Highlife music. It is essentially guitar and keyboard music which feature a whole range of hourglass drums typical of Juju music ensemble and occasionally one or two brass instruments. (i) Highlife-Jazz : A style that combines Jazz solos, chords and horn arrangements with the basic I-IV-V harmonic progression of Highlife music. (j) Ethnic/Regional Highlife: Reflects ethnic and regional identities in terms of usage of traditional musical resources, folkloric elements and linguistic attachment. Its nomenclature derives from its ethnic or regional identity e.g. Yoruba Highlife, Igbo Highlife, Esan Highlife, Edo Highlife, Isoko Highlife, Akan Highlife, Fanti Osibisaaba and so on. Theoretical Models and Approaches for African Popular Music Analysis Having examined the issues in socio-musical change, genre development, decline, revival, sustenance and their inherent flaws, distortions and ambiguities, I wish to make certain propositions toward evolving new theoretical and analytical approaches to African popular music analysis using Highlife music as a paradigm. 15 1. Social Reconstructionism Model Social Construction Social Deconstruction Social Reconstruction This indigenous model by this researcher posits that musical change does not occur in the once and for all straight-line process of birth, growth and decline of a musical genre. It rather, treats the decline of a musical style as a deconstruction in which some of the components of the older music style are then reconstructed, as they are creatively integrated within a new socio-cultural context into a novel and qualitatively distinct music idiom. It also posits that popular music genres are social constructs which can be socially deconstructed and also socially reconstructed contingent upon prevailing sociohistorical and technological processes. This circular ‘Social Reconstructionism’ model is therefore a valuable socio-historical tool for analyzing the dynamics of musical change and social dialectics in contemporary Africa . Social reconstructionism as a new theoretical paradigm, is rooted in theory of social construction which Berger and Luckman (1966), Searle (1995), Hacking (1999), Boghossian (2001) have theorized on . The process begins with the stage of construction, through the social process, moves on to a stage of ‘deconstruction’ which midwives a reconstruction process where the music takes on a new identity existing outside its original core essence. The three stages are analyzed below. The Stage of Social Construction 16 For a musical style to emerge, there must be certain pre-conditions: a. The availability of musical resources - prevailing musical sounds, musical instruments and appropriate technology that supports musical creativity; b. Availability of skilled musicians to create the new sound of music; industries that market and promote the music and the audience or social group for which the music is intended; and c. An enabling socio-cultural and economic environment which supports the development of the music in question and its labeling and classification as a musical genre. This stage is thus characterized mainly by the creative combination of available musical resources into a coherent and recognizable musical core which imputes a musical essence into the product. The ideologies and intentions of its creators are also imprinted on the style to give it meaning and musical symbolism. The Stage of Social Deconstruction Social deconstruction represents a process where the engrafted meaning, conventions, symbolism and iconography in a social construct begin to loose their absolute advantages as emergent social and historical forces act upon them. In my developmental schema , the stage of social deconstruction is characterized by these main features: a. The musical style begins to deviate more and more from its core musical essence and definitive framework. This phenomenon arises based on peripheral levels of artistic recreation and re-interpretation that are brought to bear on the original style. This again, is a reflection of individual, group, generational or new socio-technological and economic demands. b. The musical style begins to loose the original meaning of its creators. It gradually takes on added meanings and a new social identity as can be detected in the changing conventions, iconography and significations. It could possibly also acquire a new audience gradually, while loosing some old ones along the way. c. New stylistic innovations are introduced into the musical product. A deconstructed musical form may contain some elements of the old style which are combined with new stylistic innovations reflective of the prevailing socio-musical environment. 17 The Stage of Social Reconstruction. The reconstruction stage represents significant attempts towards a re-definition of the social construct in new stylistic and social terms. It is a stage of assemblage of the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ in proportions that impute new musical and social meanings into the product. The reconstruction stage is also an on-going process, a direct response to the changing social world of the art and the society at large. The main features of this stage include: 1. Multiple modes of expressions which may or may not be directly derived from the original core essence. 2. Attempts at fashioning out a new direction and a new core essence for the product. 3. Attempts at locating the musical stream within a new socio-economic, artistic and cultural space. This attempt seeks to define the social group of its audience and the social world of the product. 4. The search for new meanings through some forms of ideological mutation to reflect the changing socio-musical configuration, interactions and social mediations. How long each process in the social reconstructionism model takes is dependent on the degree of musical saturation in the society. This will also depend on the level of social interactions between the various social actors in the chain as well as their degree of social responsiveness and willingness to change. The Social Construction, Deconstruction and Reconstruction of Highlife I have demonstrated adequately in this paper that Highlife music is a social construction. I have also stated that Highlife music exists in diverse forms reflective of the ethnic and regional diversities of host societies as well as differences that articulate authorial and artistic autonomy. My graphic representation of the historical development of Highlife music earlier on highlighted the relationship that exists between social forces and musical change and how these affect the social perception of Highlife in contemporary times. We can thus safely deduce that Highlife has deviated significantly from its core musical and social essence at its inception in the 1950s when the dance band 18 format was popularized in the West African sub-region. The social, musical, ideological, economic and technological backdrop against which Highlife music developed in the 1950s have undergone several changes over time. These have significantly re-defined Highlife in new social, musical, economic and ideological terms. Highlife has thus, gone through a process of deconstruction. This stresses the need for a social reconstruction of the term ‘Highlife music’ in the light of current global socio-musical realities. 2. Core and Periphery Model or Diffusion Theory Core Periphery level 1 Periphery level 2 Periphery level 3 Periphery level 4 etc The core and periphery analytical model is an intersection of essentialism and social constructionism and represents in a way, diffusion theory. This model posits that despite the social construction and social immersion of the African popular music genre, there are some fixed traits which define it in specific musical terms. When a musical genre has been created through socio-historical and socio-musical processes, the social and musical elements of its creation imputes into it a core essence which is recognizable and identifiable. From this core essence emerges peripheral levels of artistic re-creation 19 and re-interpretation contingent on prevailing forces of change, generational modification and geographical spread. The various peripheral levels of re-creation are shown in different colors in the diagram; each color depicts the changing form of the genre relative to the core. In the case of Highlife, E.T. Mensah’s dance band Highlife incarnation created in the 1950s and by extension Ghanaian Highlife, could be taken to be the core of the West African Highlife against which backdrop, other re-creations and transformations of the genre can be measured in artistic and cultural terms. The earlier proto-types (like Kokoma, Osibisaaba, Agidigbo, Gumbey and Odonson) bear a double toga of being the forerunners of the dance band format alluded to in modern terms as ‘original’ or ‘classical’ Highlife, and being at the same time, a ‘poor man’s’ versions of the classical Highlife. Both the core and the various peripheral levels can be studied separately and also in relation to the core. 3. Historical and Contemporary Approach African popular music scene both in the past and in the present, has been on the receiving end of various foreign socio-musical influences which greatly affect the stability and definitive framework of popular music traditions. Consequently, managing socio-musical changes on the African continent has been a major challenge because of the rapidity of these changes which have been accelerated in this age of ICT and globalization. Some of these changes and their effects on musical developments have been shown in our graphic historical representation of Highlife in Ghana and Nigeria earlier on. To understand, interpret and situate these changes within socio-musical and historical contexts, I suggest that African popular music genres be studied synchronically (i.e. as a slice of time in history) and diachronically (along a historical continuum) as I deed in my research on Highlife. In this case, developmental trends and changes can be situated in molds and then studied within particular socio-historical contexts as well as along a historical path. Because of the social and technological upheavals of the 21st century, African popular music forms are best studied using a historical and contemporary approach. In each case, the social and aesthetic benchmarks for assessment will be based on historical specificity and historical relativity. 20 Conclusion The generic boundary of what we call Highlife in recent times is fluid and amorphous. At the same time, the social perception of what constitutes Highlife in contemporary terms is a point of dispute between musicians and generational groups. Highlife as a socio-musical phenomenon, has been deconstructed through series of developmental and transitional changes. We can thus speak of Highlife styles within the Highlife generic tradition. Highlife styles are alive in Ghana and in Nigeria and are replicated in various forms of popular music which do not necessarily bear the name Highlife. Because African popular music can not be compartmentalized in strict stylistic and geographical contexts, what exist in practice are ‘family resemblances’ which share a basic musical language and contextual usages. I will conclude here by agreeing with these genre theorists: Neale’s (1995:464) submission that definitions of a genre are always historically relative and therefore, historically specific; Buckingham’s (1993:137) assertion that a genre is not simply given by a culture, but that it is in a constant process of negotiation and change and Miller’s (1984) submission that “the number of genres in any society depends on the complexity and diversity of that society”. My three theoretical and analytical approaches proposed in this paper are derived from these premises as well as Linda Ackerman’s change models. These approaches will be of significant benefit as analytical tools for African popular music analysis and to support my thesis that African popular music is in a constant state of re-creation through a negotiated process of continuity and change. 21 Notes 1 Oral consultations with Goddy Ojukwu (27/09/07), Anayo Okoro(16/0406) and Gloria Ekere(10/05 2007) on Highlife in Eastern Nigeria. 2 See Vanguard online January 8th, 2005 3 The copyright of the Developmental, Transitional and Transformational models belong to Linda Ackerman. They have only been used here for educational purposes. References Aig-Imoukhuede, Frank. (1975) “Contemporary Culture” In J.F.A Ajayi and A.B. Adebirigbe (eds.) Lagos: The Development of an African City. Lagos: Longman. Ajirere, Tosin. 1992. Three Decades of Nigerian Music 1960-1990.Lagos: Macboja Press. Akpabot, Samuel. 1986. “Nigerian Music as Entertainment”. A keynote address delivered at the Centre for Cultural Studies, University of Lagos, March 1986. Berger, L and Luckman, T.(1966) The Social Construction of Reality U.S.A: Anchor Press. Boghossian, Paul “What is Social Construction?” Times Literary Supplement, February 23, 2001. Buckingham, David.(1993). Children Talking Television: The Making of Television Literacy. London: Palmer Press. Chandler, David. 1997. “An Introduction to Genre Theory”(WWW Document) URL http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/intgenre.html. Visited on 3/9/06. Collin, John. (2005) “History and Development of Highlife”. An unpublished manuscript. Collin, John. (2004) “A Historical Review of Sub-Saharan African Popular Entertainment”. In Esi Sutherland-Addy and Takyiwaa-Manuh (eds.) Africa in Contemporary Perspective (in Press) Collins, John. 1992. West African Pop Roots. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Emielu, Austin 2009. “Origin, Development and Sustenance of Highlife Music in Nigeria”. An unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Ilorin, Ilorin Nigeria Euba, Akin (1975) Yoruba Drumming: the Dundun Tradition. Bayreuth: African Studies 21/22 Feuer, Jane 1992. “Genre Study and Television”. In Robert Allen (ed.) Channels of Discourse, Reassembled: Television and Contemporary Criticism. London: Routledge. Gledhill, Christine. 1985.”Genre”. In Pam Cook (ed.) The Cinema Book .London: The Film Institute. Hacking, Ian (1999) Social Construction of What ? Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Idonije, Benson.2001 “Travails of Nigerian Musicians” .The Guardian October Lagos: Guardian Press. Jick, Todd & Peiperl Maury (2003).Managing Change: Cases and Concepts .London: McGraw Hill Irwin. 22 Miller Carolyn. 1984.”Genre as Social Action”. Quarterly Journal of Speech no.70 Neale Stephen. 1995. “ Questions of Genre”. In Oliver Boyd-Barret and Chris Newbold (eds.) Approaches to Media: A Reader. London: Arnold Neale, Stephen (1980). Genre . London: British Film Institute. Obidike, Mosun. 1994. “ New Horizons in Nigerian popular Music”. A paper delivered at the Pana-Fest mini-conference in Ghana 13 -14 December. Ogisi, A.A 2004. “The Significance Of the Niger Coast Constabulary Band of Calabar in Nigerian Highlife Music: An Historical Perspective” in Nigerian Music Review No.5 Okwechime, Ndubuisi.(1984) “Highlife Revival Imminent”. Africa Music No.21, May/June 1984. Lagos: Tony Amadi Communications Ltd. Omojola, Bode. 1995. Nigerian Art Music. Ibadan: IFRA ____________2006. Popular Music in Western Nigeria: Themes, Styles and Patronage System. Ibadan: IFRA Rhodes, Steve. 1998.” Social Music in Nigeria 1920s-1990s”. Irawo Journal no 1/98 Pp1-10 Searle, John. 1995. The Construction of Social Reality. New York: Free Press Stam, Roberts. 2000. Film Theory. Oxford : Blackwell . Van der Merwe, P. 1989. Origin of the Popular Style: The Antecedents of 20th Century Popular Music. Oxford: Calderon Press. 23 Discography Abbas (1997) Odo De Nti HFO Music, London. Adeolu Akinsanya (n.d.) Baba Eto Afrodisia Ltd., Lagos DWAPS 2185. Adeolu Akinsanya (n.d.) Environmental Sanitation Afrodisia Ltd., Lagos. DWAPS 2260 Adeolu Akinsanya (n.d.) Original Highlife Afrodisia Ltd., Lagos DWAPS 2257. Awka-Cross Memories (n.d.) Ben Nig. Ltd Port Harcourt. BBLT 8334 Bright Chimezie (2007) Oyinbo Mentality Premier Music, Lagos. KMCD 083 Cardinal Rex Lawson (n.d.) Greatest Hits Premier Music, Lagos. Cardinal Rex Lawson (n.d.) Victories Premier Music, Lagos. Cardinal Rex Lawson (n.d.) The Classics vol. 1 Premier Music, Lagos. KMCD 010 Celestine Ukwu (n.d.) Igede Premier Music ,Lagos. KMCD 012 Chief Dr. Oliver De Coque (1994) Tribute to Babangida Olumo Records, Agege, Lagos. Chief Dr. Oliver De Coque (2001) Tribute to Babangida Olumo Records, Agege, Lagos. OGMRC 001 Chief Dr. Oliver De Coque (2006) Mama and Papa Olumo Records, Agege, Lagos. Chief Dr. Oliver De Coque (2000) Classic Hits Leader Records, Oshodi, Lagos. Chief Dr. Oliver De Coque (2001) Vintage Hits vol. 3 Olumo Records, Agege, Lagos. ORCD 003 Chief Dr. Oliver De Coque (n.d.) Vintage Hits vol. 4 Olumo Records, Agege, Lagos. ORCD 004 Chief Dr. Orlando Owoh & his African Kenneries (2003) Ma wo Mi Roro Compact Disc Audio Ik 523 Chief Dr. Orlando Owoh & his African Kenneries (n.d.) E Get as E Be G.C Ajani Music, Ojo, Lagos. Chief Osita Osadebe ( n.d.) Kedu America Panovo Entertainment, Alaba International market, Lagos. Chief Osita Osadebe (n.d.) 10th Anniversary People’s Club Special Premier Music Lagos, KMCD 017 Chief Osita Osadebe (n.d.) Onye m’echi Polygram Records, Lagos. 24 Chief Osita Osadebe (n.d.) Ndi Ochongonoko Premier Music, Lagos. KMCD 021 Capt. Muddy Ibe (n.d.) The Best of Capt. Muddy Ibe and His Nkwa Brothers Rodgers All Stars, Awka RASCO 144 Daddy Lumba (2006) Tokrom Lumba Production, Accra. Dr. Sir Warrior (n.d.) Ofe Owerri Okoli Music Co. Lagos. Dr. Sir Warrior (2006) Agwo Loro Ibe Ya. Afrodisia, Yaba, Lagos. DWACD 012 Dr. Victor Olaiya (1986) Dr. Victor Olaiya in the 60s Premier Music, Lagos. POLP 066 Dr. Victor Olaiya (1986) Ilu le O! Premier Music, Lagos POLP 096 Dr. Victor Olaiya (n.d.) 3 Decades of Highlife Premier Music, Lagos. POLP 186 Dr. Victor Olaiya (n.d.) Highlife Re-incarnation Premier Music, Lagos. POLP 072 E.T. Mensah and Dr. Victor Olaiya (1984) Highlife Giants of Africa Premier Music, Lagos. POLP 102 Ejeagha, Mike (n.d.) The Story of Omekagu Ehbbiy and Myk’O Music, Enugu and Lagos. Evevo Dance Band of Uzere (n.d.) Isoko ma Kwuoma gbovo Fatai Rolling Dollars (n.d.) Won Kere Si Number High Kay Dancent Ltd. Lagos. Highlife Kings vol.1(n.d.) Premier Music, Lagos. Highlife Kings vol.2(n.d.) Premier Music, Lagos. KMCD 02 Highlife Kings vol.4 (n.d.) Premier Music, Lagos. KMCD ) 051 Jesse King (2006). Buga Afeezco Music, Yaba Lagos Tira 001 Jesse King (n.d.) Mr. Jeje True Talent African Records, Ikeja Lagos. Lagbaja (2005) Africano Videos Series 1 Motherlan’ Music, Ikeja, Lagos. Lagbaja (2006) First Steps Motherlan’ Music, Ikeja Lagos. MM0603VCD. Misto Xto (n.d) Still Alive South Central Records, Calabar. (n.d. ) Best of Ghana Old School Hits vol. 2 Oriental Brothers (n.d.)“Vintage Hits” United African Artists & Film Co. Oriental Brothers International Band (n.d) Ugwu Manu na Nwanneya Super International Music, Lagos. OBI 012. Osayomore Joseph (n.d.) Boboti Boboti O.J Records, Benin City. Paulson Kalu (n.d.) Uche Chukwu Mee Possible Music Links, Apapa, Lagos. Popular Cooper (n.d.) Ahiovo Dhese Oma rai Via No Jawhono Interbiz, Ughelli. JIR 2020 25 Popular Cooper (n.d.) Oro Eme Raha Masa Jawhono Interbiz, Ughelli. JIR 2016 Prince Emeka Morocco (2002) Ife Oma House of Merchandise W.A. Ltd.Idumota, Lagos. EF 1202. Prince Niko Mbarga(1976) Sweet Mother Rodgers All Stars Awka, Robert Danso (n.d.) Canadoes Int. Band Ghana Rogana Ottah Live Concert God First Music, Obiaruku. Rogana Music 002 Sir Victor Uwaifo ( n.d) Joromi Polygram Records, Lagos. Sunny Neji (2005) Oruka Ojez Music, Lagos. Sunny Neji (2006) Of De Hook Ojez Music, Lagos. The Best of Master Kwabena Awkaboa (n.d.) Evergreen Tunes Papcad, Accra, Ghana. The Best of Yamoah vol. 3 (n.d.) Accra , Ghana Tilda and the Rokafil Jazz International (n.d.) Who Knows Tomorrow Rodgers All Stars, Awka. Tosin Martins (n.d.) Happy Days Westside Music Inc. Victoria Island Lagos. Voice of the Cross (n.d.) Gospel Highlife Ugoh and Co., Aba VOCO12. 26