Affirmative Action - Lifelong Learning Academy

advertisement

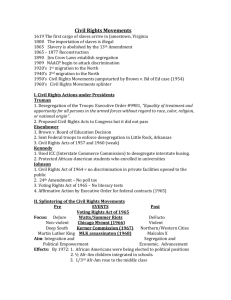

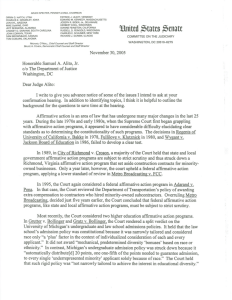

Affirmative Action The issue: Does the Constitution allow government to classify on the basis of race if the law is intended to benefit a previously discriminated against minority? Introduction Cases In his famous dissent in Plessy v Ferguson, Justice John Harlan wrote that the law was "color blind." Recently, Harlan's phrase has found new currency among critics of government affirmative action programs that began to spring up in the 60s and 70s. Affirmative Action in the Schools Bakke v. Regents, Univ. of California (1978) Grutter v Bollinger (2003) Parents Involved v Seattle School District May the government use racial classifications (2007) when it does so to benefit, not discriminate Fisher v University of Texas (2013) against, racial minorities that have historically Schuette v Coalition to Defend Affirmative been the victims of discrimination? The Supreme Action (2014) Court first considered that question in 1978, in the case of Bakke v. Regents, University of California. Bakke, a white applicant to the UCDavis Medical School, claimed that he was denied admission even though his test scores and grades were markedly better than minority applicants who were admitted. The Court found that Bakke had been denied equal protection of the laws by UCDavis's use of a "two-track" admission system, one track for whites and one for non-whites. Even though Bakke won, many people came to view Bakke as a victory for proponents of affirmative action. Justice Powell, providing the critical fifth vote for Bakke, said in his concurring opinion that increasing racial diversity in classrooms was a compelling state interest, and that a more narrowly tailored program--such as one that gave "pluses" to minority applicants rather than putting them into a seperate admission track--would not violate the Constitution. Recently, the Fifth Circuit has predicted, in a case involving a challenge to the affirmative action program at the University of Texas (Hopwood v. Texas), that the Court would not follow Bakke today. The Fifth Circuit found UT's use of race in its admission process to violate the Constitution. Allan Bakke. Richmond v J. R. Croson considered affirmative action in the context of government "set-asides": programs that set aside a specified percentage of Minority "Set Aside" Programs Richmond v. J. R. Croson (1989) Adarand Constructors v Pena (1995) Link Government Interests Asserted in Bakke Questions 1. How should we evaluate discrimination between racial minorities? For example, what if an affirmative action program for school admissions were to extend preferences to blacks and Hispanics, but not Native Americans? 2. How should a court evaluate a claim of discrimination by someone complaining of exclusion from a protected class? For example, if a school admission program classified someone with two black grandparents as "black," but someone with one black grandparent as "white," could the student classified as white support a claim of unconstitutional discrimination? What standard of review should apply to such state line-drawing? 3. Which of the various state interests alleged by California in the Bakke case seem the most compelling to you: (1) remedying past societal discrimination, (2) increasing the number of minorities in the legal profession, (3) increasing legal services for underserved populations, or (4) increasing diversity in the classroom? Do you agree with Justice Powell's analysis with respect to whether UC-Davis's government contract dollars for minority business enterprises. Rejecting the argument that racial set-asides might be justified as a remedy for past societal discrimination, the Court held that such programs are only justified as a remedy for past discrimination by the government entity adopting the set-asides. Croson, and a subsequent case involving a federal set-aside program (Adarand Constructors v Pena (1995)) make clear that all racial classifications will be subject to the strict scrutiny test requiring demonstration of a compelling state interest and use of classifications narrowly tailored to further that interest. In 2003, the Court decided two cases challenging affirmative action policies at the University of Michigan--one involving the law school (Grutter v Bollinger) and one involving the undergraduate college (Gratz v Bollinger). The result was a split for Michigan, with the Law School's more individualized consideration of race upheld on a 5 to 4 vote, and the undergraduate school's more blatant heavy weighting of race as a plus factor struck down, 6 to 3. Justice O'Connor's opinion for the Court in Grutter adopted much of Justice Powell's reasoning in Bakke. O'Connor found the Law School's asserted interest in creating a diverse student body to be a compelling justification for its consideration of race, and found the school admission policy appropriately considered race along with many other characteristics or experiences that could contribute to diversity. O'Connor cautioned, however, that affirmative action programs should have some termination point, and she suggested that in another twenty-five years a similarly structured program would be unlikely to stand. Most recently, in two 2007 cases (Meredith v Jefferson County and Parents Involved v Seattle Schools), the Supreme Court struck down programs in Louisville and Seattle that used the race of students as a factor in assigning students to schools so as to maintain a targeted level of racial diversity in public schools. Chief Justice Roberts (joined by Scalia, Thomas, and Alito) would prohibit all attempts to "racially balance" public schools outside of the higher education context, concluding that no compelling interest exists for such efforts. Justice Kennedy, providing the fifth vote to strike down the plans, saw the problem as one of a lack of narrow tailoring. Kennedy suggested that attempts to achieve racial balance in public schools would be constitutional if they focused, for example, on placement of new schools in racially integrated classification was a narrowly tailored means of serving the vaious interests alleged? 4. Is Justice Powell's opinion in Bakke "the law"? Why or why not? 5. Should "benign" racial classifications be subject to strict scrutiny or, as the four dissenters in Bakke argued, intermediate scrutiny? 6. Does the Bakke court hold that more qualified applicants have a right to admission ahead of less qualified applicants? 7. Is it the job of a lower court to predict how the Supreme Court might decide a case today, or should it apply existing Supreme Court caselaw even when it thinks the current Court would reject it? 8. Is your view of the correctness of the Court's result in Croson at all affected by the fact that five of the eight city council members voting on the Richmond set-aside program were black--including five of the six "yes" votes? Supporters of Seattle's efforts to racially balance its schools 9. Does Justice Kennedy's concurrence in Parents Involved v Seattle leave school districts with adequate tools to maintain integrated schools, or are school districts in many metropolitan areas bound to slide back towards segregation--albeit the result of housing patterns, rather than de jure segregation? 10. Does the opinion of Chief Justice Roberts in Parents Involved v Seattle suggest that four members of the Court are ready to overrule Grutter? 11. Both the majority and the dissent in Parents Involved v Seattle claim the mantle of Brown v Board. Which side has the better argument? 12. In Grutter, Justice O'Connor, while upholding the affirmative action program in question, wrote, "We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today." Can we assume that the Grutter holding has an expiration date of 2028 and no racial preferences will be deemed constitutional after that date? Jennifer Gratz (L) and Barbara Grutter (R), plaintiffs in affirmative action suits against the Univ. of Michigan. (CNN) 13. Fisher has every indication of being a compromise decision. Why do you think Justices Breyer and Sotomayor joined the Court's opinion, and why do you think Justice Kennedy pulled back from declaring any individualized consideration of race to be unconstitutional, as he was widely expected to do in the case? neighborhoods--rather than relying on a "crude" racial classification of students. Abigail Fisher In 2013, the Court announced its decision in Fisher v University of Texas, involving a challenge to the university's use of race as part of a two-pronged effort (the first prong being a "race-blind" policy of automatically admitting students graduating in the top 10% of their Texas high school classes) to increase the number of non-white students. The Court, in a 7 to 1 decision authored by Justice Kennedy, found that the courts below gave too much deference to the university and failed to apply appropriately strict scrutiny. Adopting a tougher standard than either Bakke or Grutter, the Court said, "The reviewing court must ultimately be satisfied that no workable race-neutral alternatives would produce the educational benefits of diversity. If a nonracial approach . . . could promote the substantial interest about as well and at tolerable administrative expense, then the university may not consider race." Justice Ginsburg dissented, finding that Texas satisfied the Grutter/Bakke standard, while Justice Thomas, concurring, would have overruled Grutter and banned all consideration of race in the admissions process. The Court noted that it was not deciding to overrule Grutter because it had not been asked to do so, leaving open that possibility for a future case. The Fisher decision is certain to spawn more lawsuits. Following the Court's decision in Grutter upholding the use of race as a factor in admissions decisions at the University of Michigan, the voters of Michigan adopted a constitutional amendment banning the racial preferences in school admissions. That amendment was challenged in 2014 by groups that argued that the amendment violated the Equal Protection Clause by denying minorities the opportunity to restore racial preferences in the state legislature, rather than through the more difficult process of constitutional amendment (Schuette v Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action). The challengers cited a line of cases that suggested, at a minimum, that state constitutional amendments enshrining a private right to discriminate are constitutionally suspect. Voting 6-2, however, the Court ruled that the voters of Michigan are free to decide whether or not to extend racial preferences in admissions. This was not, the Court made clear, a case where a constitutional amendment placed obstacles in the 14. If you were university counsel, after Fisher, what advice would you give to campus officials interested in increasing minority enrollment? 15. Schuette leave no doubt that states are free to ban affirmative action. How many states are likely to take that path? path of minorities seeking equal treatment under the law or which encouraged private discrimination in any way. The Firefighters Case" (Ricci v DeStefano)(2009) In a case that played a major role in the Sotomayor confirmation hearings, the Supreme Court reversed a ruling of Justice Sotomayor's former court, the Second Circuit, and found that New Haven's decision to throw out a promotion exam that would have resulted in 17 whites, 2 Hispanics, and no blacks promoted within its fire department violated Title VII. The Court did not reach the white firefighters' Equal Protection Clause argument, but the four dissenters (Ginsburg, Stevens, Breyer, and Souter) did, finding no violation of the Fourteenth Amendment in New Haven's action. Justice Kennedy, writing for the Court, drew analogies from equal protection precedents in reaching his result. The failure of New Haven to show a "strong basis in evidence" that its decision to throw out the test was necessary to counter past racial discrimination, Kennedy says, supports the conclusion that the city violated Title VII.