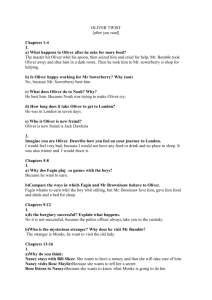

Charles Dickens: Oliver Twist

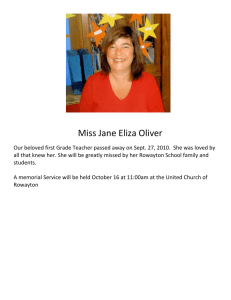

advertisement