Operations Management: Chapter 1 - Introduction & Key Concepts

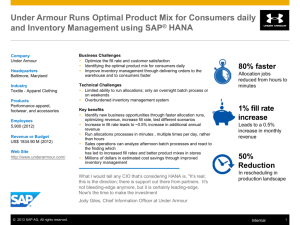

advertisement