FY 2015 IHS Budget Full Report

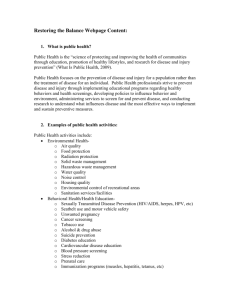

advertisement