Flightline - Allied Pilots Association

All the World’s a Stage

BY CAPTAIN DAVID J. BATES, APA PRESIDENT

In Shakespeare’s play “As You Like It,” one of the characters proclaims that “all the world’s a stage,” which pretty well summarizes the current state of the airline industry. Large international carriers such as American Airlines now compete globally and have embraced alliances as a method of bolstering their respective networks. Like it or not, American Airlines is a key player in the oneworld Alliance and has a great deal at stake in the success of its ties to British Airways, Iberia, Japan

Airlines, Qantas and other oneworld member carriers.

Meanwhile, the United States continues to forge “open skies” agreements with other countries, having recently observed the signing of the 200th such agreement. These agreements facilitate access by foreign carriers to the U.S. aviation market, which remains the world’s largest and most lucrative. This ever-increasing competition poses a variety of challenges for our nation’s airlines — and, not incidentally, for the pilots whose livelihoods depend on the continued viability of those carriers.

As your elected leadership, it’s our responsibility to help ensure that we are taking all reasonable measures to protect your career interests as the globalization of our industry proceeds. Last month an APA delegation participated in the

International Federation of Airline Pilots (IFALPA) Conference 2011 in Chiang Mai, Thailand, which featured the first-ever

Global Pilots Symposium. As the U.S. delegate to IFALPA, the Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) invited APA to attend the conference and participate in the symposium. More than 300 attendees from around the world were on hand, including pilot union leaders from the SkyTeam, Star and oneworld Alliance airlines.

After we initially reported APA’s participation, I received a couple of inquiries from members asking why we are participating in global pilot alliance meetings. It would be difficult to overstate the value of an APA presence at this conference.

Ignoring the significance of the changes that our industry is experiencing on a global scale and how those changes could affect us as pilots would be a serious strategic error.

One useful byproduct of our attendance was the agreement we reached with the British Air Line Pilots’ Association

(representing British Airways’ pilots) and SEPLA (representing the Iberia pilots) to pursue the establishment of a protocol that ensures appropriate proportionality of flying for our three pilot groups. This protocol would require the consent of all three unions and American Airlines, British Airways and Iberia management. Once agreed to, it would then be integrated into our respective collective bargaining agreements.

Based on highly productive discussions abroad with Captain Barry Jackson, president of the Australian and International

Pilots Association counterparts (representing all Qantas Group pilots), Captain Jackson and I agreed to build closer ties between our two unions. With American Airlines putting its code on direct service between Sydney and Dallas/Fort Worth beginning in May, and the recently announced Qantas/American joint business agreement, it’s incumbent on our two pilot groups to get to know each other better. In mid May, I invited Captain Jackson to address the APA Board and shortly thereafter signed the first mutuality agreement between the pilots of the AIPA and the pilots of American Airlines.

Also, Qantas provides a first-hand look at some sobering industry trends — some new and others not so new — with rapidly growing Emirates now offering service in Qantas’ bread-and-butter Australia-New Zealand markets. I’ll have more to report on Emirates and other Middle Eastern carriers in a moment. In addition, increasing amounts of Qantas’ former mainline flying has shifted to several Qantas-owned alter-ego carriers. Have we seen that play before?

All four of the APA representatives who attended the conference — Vice President First Officer Tony Chapman, International

Alliance Committee Chairman Captain TK Kawai, Government Affairs Committee Chairman Captain Bob Coffman and I

— participated in panel discussions. As someone who was heavily involved with flight time duty time discussions between

CAPA, ALPA and APA, I spoke about the role pilot alliances should play in shaping the regulatory environment, including flight- and duty-time rules. Captain Kawai participated in a panel on the challenges and opportunities resulting from joint ventures, and Captain Coffman joined the discussion on the ramifications of open-skies agreements.

Other notable panelists and speakers included Duane Woerth, the U.S. ambassador to the International Civil Aviation

Organization and a former president of ALPA; ICAO Chief of Flight Operation Mitch Fox; Star Alliance CEO Jaan Albrecht;

Seth Rosen, director of the International Pilot Services Corporation (an ALPA subsidiary) and APA’s professional negotiator; and ALPA Economic and Financial Analysis Department Ana McAhron-Schulz, who is also assisting us in our negotiations.

One particularly eye-opening topic of discussion was the rise of Middle Eastern carriers Emirates, Qatar, Etihad and Gulf

Air, which ALPA President Captain Lee Moak has also been highlighting in other recent industry (continued on page 18)

Flightline

2 May 2011

May 2011

A R T I C L E S

4

A Perspective on Negotiations

5

Bankruptcy, the Solution to American Airlines’

Troubles — or Just Another Strategic Misstep?

6

Divesting American Eagle

8

TSA Advanced Imaging Screening Technology

10

Can Experience be a Bad Thing?

11

Yes, the A and B Plans Do Have Annuity Options

14

Pilots and Acute Stress Disorders

16

American Heroes

Shutting down an engine changes everything

17

APA Launches New Alliedpilots.org

Members’ Home Page

R E G U L A R I T E M S

19

CLASSIFIEDS

22

FINANCIAL MATTERS: Monthly Pension Factors

22

IN MEMORY

23

APA CONTACT INFORMATION

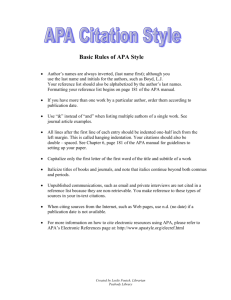

APA-AA negotiations, May 5, 2011.

Cover photo courtesy of Neta Robinson,

APA Benefits Manager —

Life & Health, HIPAA Privacy

Flightline is the official publication of the Allied Pilots Association, representing the pilots of

American Airlines.

National

Communications

CA Sam Mayer (LGA), Chairman

FO Tom Hoban (DFW), Deputy Chairman

FO Kent Calvin (DFW)

FO Jennifer Ewald (DFW)

FO Mark Fowler (DFW)

FO Craig Railsback (DFW)

FO Howard Schack (DFW)

FO Dennis Tajer (ORD)

CA Richard Vojvoda (SFO)

FO Stephen Wiggins (MIA)

Communications Director

Gregg Overman

Communications Editor

Jennifer Arend

Flightline Editor

FO Tom Hoban

Design and Layout

Stacey Hull, Graphic Designer

Printing Services Manager

Bruce Rushing

SUBMIT ARTICLES TO:

Flightline

Attn: Gregg Overman

Communications Director

Allied Pilots Association

O’Connell Building

14600 Trinity Boulevard, Suite 500

Fort Worth, Texas 76155 -2512

E-mail flightline@alliedpilots.org

SUBMIT CLASSIFIEDS TO:

Flightline Classified Ads

Attn: David Dominy

Media Coordinator

E-mail ddominy@alliedpilots.org

Flightline magazine is collaboratively written by the

APA Communications Committee and APA staff.

Any member in good standing can submit an article for consideration. All articles must comply with APA’s policies, guidelines and positions as established by the

APA Board of Directors, National Officers, Constitution and Bylaws and Policy Manual. Articles should address issues pertinent to APA and its pilots, and must avoid references of a personal or political nature. If you wish to submit an article or a letter to the editor, please send it to flightline@alliedpilots.org.

All articles are edited and vetted by APA Communications, the National Officers and APA Communications

Department.

www.alliedpilots.org

3

Flightline

A Perspective on Negotiations

BY SETH ROSEN, DIRECTOR OF THE INTERNATIONAL PILOT SERVICES CORPORATION

Six months ago, APA President Captain Dave Bates called me to see if I was interested in working with the union and its

Negotiating Committee. I was somewhat familiar with the status of negotiations at American and the challenges facing all employees at AA in the current round. After considerable thought and further discussions with Dave and others, I felt that this was an opportunity to apply my experiences and skills to help APA achieve a positive result in the negotiations for the benefit of the AA pilots.

I have been representing pilots in virtually every aspect of their jobs and in every forum for 40 years. I started with the Air Line

Pilots Association as a labor lawyer in 1971 handling contract enforcement matters, Federal Aviation Administration matters and National Transportation Safety Board accident investigations.

Later, I transitioned into the negotiations arena. For almost 20 years, I was ALPA’s director of representation responsible for overseeing all negotiations, contract administration matters, FAA and NTSB matters and organizing activities. In that capacity, I was directly involved in numerous negotiations ranging from those held to combine Continental Airlines and Texas International in

1982 to the milestone agreement achieved at Delta Air Lines in

2001. I have represented airline labor on two industry committees that reviewed the performance of the National Mediation Board and made recommendations for improvement of their services.

And in 2008, I served on President Obama’s transition team, with responsibility for reviewing the NMB.

Since retirement from ALPA in 2003, I have continued to be directly involved in negotiations in the United States and internationally as director of the International Pilot Services

Corporation. But that’s more than enough about me. Let’s turn to my perspective on the current negotiations.

The Process

Negotiating collective agreements is the primary function of labor unions. It is a multifaceted process that requires development of a comprehensive strategic plan. The strategic plan for negotiations under the Railway Labor Act has many components and traditionally four phases — preparation, negotiations, mediation and super-mediation. The plan requires that a timeline be developed that is f luid and adaptable to changing circumstances. Since I entered into these negotiations well into

Phase 3 (mediation) with the talks recessed, I have been in catch-up mode.

First, I collected as much information as possible to gain an understanding of the overall context of the negotiations. Then I met with the Negotiating Committee and APA leadership to assess the situation and develop an overall plan for bringing the negotiations to a successful conclusion. The next step was to meet with American Airlines management and agree to a negotiating protocol to resume negotiations and set a schedule and agenda for meetings. Since January, progress has been slow but steady and the protocol has been extended, with meetings presently scheduled through the end of June.

Now that I have had the opportunity to work closely with the

Negotiating Committee and the APA leadership over the past several months, I have a much better understanding of the complexities of these negotiations. Here we are — eight years from the last collective bargaining agreement and nearly five years into the current negotiations/mediation, and we still have a considerable distance to travel to attain a positive outcome in these negotiations. Almost everyone is frustrated, angry and distrustful of management, largely because of the company’s performance, combined with the continuing management compensation program.

The Challenge

The challenge is reaching an agreement that meets the needs of the pilot workforce and provides American Airlines with the tools for implementing a new business plan including such items as ultra long haul language, an enhanced reserve/scheduling system and new aircraft pay rates. Since resuming negotiations in January under the bargaining protocol, considerable progress has been made. The Negotiating Committee is now tackling one of the most difficult and important subjects — scheduling.

The results of these scheduling negotiations will have a direct bearing on the next phase of negotiations and the ability to reach a timely agreement.

My greatest concern, and what occupies most of my time, is how to help bring these negotiations to a timely and successful conclusion. After nearly five years, the conventional approach has clearly not worked in our favor. We need to find a way that moves the process forward and produces a timely and positive result.

One thing I do know, is that after all these years of working with pilots, it is you , the line pilot, who will make the difference in the end. Your unity of purpose and your support of APA’s leadership is the key to empowering them and enabling them to achieve a successful outcome.

That is why it is so important to stay informed, provide input to your leadership, be involved in the process, understand the issues, and be prepared to vote on a new contract.

Flightline

4 May 2011

Bankruptcy, the Solution to

American Airlines’ Troubles

─

or

Just Another Strategic Misstep?

BY STL CAPTAIN DOUG GABEL, STL DOMICILE CHAIRMAN

In an Oct. 7, 2010 Business Week article entitled “Why American

Airlines Is Stuck At the Gate,” author Mary Schlangenstein promotes the theory that American, once the global leader in airlines, is now a failing carrier because it elected to forgo bankruptcy in 2003. As the price of fuel continues to rise and American continues to underperform financially, you can expect to hear this refrain get louder. Don’t be swayed by the rhetoric, it is meant to make you feel that somehow all of this is your fault.

It’s as if the pundits promote bankruptcy as a sign of success rather than the failure it really is.

“American is paying the price for sidestepping the near-death experiences of its competitors,” Schlangenstein writes. The article is centered on American Airlines management’s claim that the carrier’s labor costs are the only significant impediment keeping it from being competitive.

Later in the article, Schlangenstein quotes analyst Hunter

Keay: “They’re playing the hand they were dealt by avoiding bankruptcy and it is costing them dearly.”

Really? Is that all it takes? Just declare bankruptcy and all of

American’s problems are solved? If you can’t get your employees to be engaged in your business, just jump into bankruptcy court and let a judge cram what you think is the appropriate medicine forcefully down the throats of your employees. Seems like a nobrainer, right? After all, these malcontent employees just don’t understand what’s required to compete in the airline business these days.

The Business Week article and current analyst groupthink leads you to a quick assumption that American’s legacy competition

— United, Continental, Delta and Northwest — have all visited the bankruptcy courts recently and had their labor contracts modified, while American has not. Since these other carriers appear to be performing financially better than American, you might conclude if you’re willing to gloss over the dramatic human toll bankruptcy has on its employees, taking a trip through bankruptcy court to eviscerate labor contracts is the common denominator of success for airlines.

Let’s consider for a moment the fact that Continental, while a frequent visitor to bankruptcy in the past, has not filed for

Chapter 11 since 1990, according to a list of bankrupt carriers and service cessations produced by the Air Transport Association.

Since its last bankruptcy, Continental has had a very public change of senior leadership and gained a reputation in the industry for quality management and good labor relations. It is now merging with United.

Delta Air Lines, having joined with labor to prevent a takeover by US Airways, went on after exiting bankruptcy to jointly facilitate a merger with Northwest. The US Airways-

America West merger, on the other hand, is just a mess, as the carriers have yet to complete the integration and continue to operate as two separate airlines.

The ATA list, while unofficial, cites 188 bankruptcies or service cessations since deregulation began. The sample size of American

Airlines legacy competitors taking a ride through the bankruptcy courts and now outperforming American is down to two.

Not good odds, if you ask me.

A quick read through the ATA list will disavow you of the notion that filing for Chapter 11 is the road to success, particularly if you consider the fact that many of the bankrupt carriers have made multiple trips through the courts.

In addition, bankruptcy does more than impact labor — it also wipes out the common shareholder, who today has a $1.8 billion stake in the enterprise. Bankruptcy also damages suppliers, debt holders and a host of other players. Is it really worth the damage to all these stakeholders to have a judge impose contractual changes because management has failed in the leadership role it is charged with performing?

Bankruptcy isn’t the answer

In 2003, Don Carty, then CEO of American, came over to APA headquarters to speak to the Board of Directors about the state of the airline and to explain that management believed they needed $1.8 billion a year in labor concessions and $2.2 billion a year in non-contractual savings to survive as a continuing entity.

As I listened to him speak, two questions were burning through my mind — first, what took you so long to come over here and ask for our help, and second, if you could save $2.2 billion a year outside of labor contracts, why hadn’t you already been doing it?

Yes, I know I am supposed to be a labor leader, but come on, what took them so long to address the glaring problems brought on by the 2001 terrorist attacks and their subsequent effect on the economy? Between Sept. 11, 2001 and the second quarter of

2003 when the concessions took effect, according to Capital IQ

(a division of Standard and Poor’s that (continued on page 7)

Flightline

May 2011 5

Divesting American Eagle

BY LAX FIRST OFFICER TIM HAMEL, SCOPE COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN

Over the past several months, there has been much discussion and speculation about the potential divestiture of American

Eagle by AMR. Through this report, the Scope Committee hopes to answer some of the more common questions and dispel many of the misconceptions surrounding the sale or divestiture.

Initially, AMR considered three different forms that the transaction could take: an outright sale to either another certificate holder (airline) or a financial group (private equity), a sale of stock in an initial public offering (IPO), or a spin-off in which shares of the new Eagle company would be issued to existing AMR shareholders. The proposed sale of Eagle was also considered in 2007, but then, as now, there was very little interest shown in the form of potential purchasers. This, combined with an unfavorable environment for a regional airline IPO, makes the spinoff option the most feasible scenario.

Regardless of what form the divestiture takes, one of the most problematic aspects of any deal would be determining who would guarantee the debt on the Eagle aircraft, which is currently estimated to be in excess of $1 billion. This is made even more challenging by the significant level of exposure to the 50-seat and fewer aircraft that Eagle operates. Delta was successful in recently selling Compass and Mesaba, as they each had much less (in the case of Compass, zero) exposure to the 50-seat and smaller aircraft market. However, Delta did have to announce significant reductions (reported as high as 50 percent) in its

Comair operation due to the much higher percentage of 50-seat capacity, in order to gain any interest from potential purchasers.

While there still remain a number of markets where 50-seat aircraft can viably operate in support of network feed, that number decreases with each increase in the cost of a gallon of Jet A. The prospect of another carrier taking on this level of debt for more than 200 Eagle aircraft that have a current value roughly equivalent to what InBev could utilize them for as beverage cans seems unlikely even in an industry that has collectively failed to earn its cost of capital during the past two decades.

An additional concern for any potential divestiture scenario is the need for AMR to include a substantial capacity purchase agreement (CPA) — also referred to as an air services agreement

— in which the new entity would be guaranteed a contract to operate a minimum number of f lights/ASMs/aircraft in feeding

AA for several years. The lack of a significant enough CPA has been cited as a potential cause for the tepid response to the sale of Eagle in 2007.

The recent sale of Compass to TransStates, Mesaba to

Pinnacle, Expressjet to Skywest, and the ongoing attempt by

Delta to sell off Comair are all part of the larger consolidation of the regional industry. The past decade has seen unprecedented growth of these carriers as the bankruptcy process has been utilized by mainline carriers to extract sizable scope concessions.

But with aforementioned economics of flying 50-seat and smaller aircraft continuing to diminish, there will be increased competition for the limited opportunities.

The Boyd group estimates that nearly 600 regional aircraft (mostly 50-seat and smaller models) will exit the system between now and the year

2013, which coincidentally is also when the Eagle pilot contract becomes amendable. All this signals that the days of regional agreements with guaranteed “cost plus” terms are coming quickly to an end. Even Gerard Arpey stated in a recent earnings call that the economics of flying such aircraft do not work. These basic economic considerations, combined with the aggressive push-back against expanded outsourcing in the combined UAL-

CAL organization and the success in their related grievance, are indicative of the consensus that is building — that the open season on this particular outsourcing of our careers may be coming to an end.

More important to the pilots at AA is what the potential implications of the Eagle divestiture would be to our work group. To fully understand these, it is necessary to reference our current contract and the exemptions pertaining to the Eagle operation:

• As a commuter carrier, Eagle and all other commuter carriers are required to operate aircraft with fewer than 50 seats and weighing less than 64,500 pounds. (1.B.4)

• Eagle and all other commuter carriers are held to the aircraft count limit of 110 percent of the narrow-body aircraft operated by mainline AA. (1.D.5.a-e)

• American Eagle Inc. and Executive Airlines Inc. can, in the aggregate, operate 43 ATR or equivalent 51-70 seat turboprop aircraft under their certificates and continue to be considered commuter carriers for the purposes of our contract. (1.D.2)

• Under the exemption created by Letter SS, American Eagle is currently permitted to operate the 47 CRJ-700 aircraft that are on the property or on order. The aircraft and the exemption to operate them under the commuter exemption are “hullspecific.” In other words, if a tornado were to hit D/FW and destroy five CRJ-700 aircraft, American Eagle would then be limited to the remaining 42 aircraft. (Letter SS as amended by arbitrator Bloch’s decision on Grievance P-14-07)

There are some differences between the contractual exceptions for the majority-owned or affiliate, and non-affiliate carriers that could impact a divested Eagle operation:

• As a majority-owned or affiliate, Eagle is allowed to operate nonstop scheduled service between major airports, subject to a limitation of a combined 1.25 percent of AA’s total scheduled block hours (1.D.5.h, as amended by Letter VV). Non-affiliates

Flightline

6 May 2011

are not permitted to perform this f lying without the consent of APA.

• Eagle is contractually required to operate only 85 percent of its f lights so that they originate or terminate at a major airport

(DFW, ORD, MIA, JFK, SFO, LAX, LGA, STL, BOS and SJU, as defined in 1.D.5.H and amended in letter VV). Non-affiliates are required to operate all of their flights into or out of these airports.

Another scenario that is often discussed involves the question:

If another carrier such as JetBlue acquired Eagle or Republic, could it just codeshare and fly larger equipment on the former

Eagle routes? To be perfectly clear, if Republic or any other carrier purchased Eagle, it would still be limited to the restrictions related to non-affiliates as long as it intended to operate under

1.D, the commuter exception. If an acquiring carrier chose to pursue a codeshare relationship, it would be required to comply with the mediation-arbitration process and related restrictions outlined in Section 1.H of our contract. This process would be no different than if management pursued a codeshare with any other domestic air carrier, and it would have to perform this f lying on one of the other certificates that it holds (Republic currently has five), or it would forfeit its ability to f ly under the provisions of 1.D of our contract.

Regardless of what form the divestiture of the Eagle operation takes — or if it takes place at all — the Scope Committee will closely monitor the developments and ensure that any new operation remains in compliance with Section 1, the scope clause of our contract.

Bankruptcy, the Solution to American Airlines’ Troubles?

(continued from page 5) provides financial data), AMR lost a grand total of $6.884 billion in earnings before taxes.

The reason for the delay, in my view, was that Carty had not spoken directly to the pilot’s union or its leadership in years , a result of the huge rift between labor and management caused by the Reno Airlines acquisition and the ensuing pilot sickout protesting management’s handling of the situation.

Even though the labor/management relationship was seriously defective in 2003, the employees reached consensual labor contracts with management. Management made their case with the employees, and the workforce responded by doing what was required. Those agreements, however, were almost derailed at the eleventh hour when Securities and Exchange Commission filings showed that Carty had set up a rich retention plan for senior management at the same time he was extracting massive concessions from American’s employees. It turned out to be a huge labor relations blunder that ultimately cost Carty his job.

In the years since that fiasco, the relationship has only marginally improved. Management’s decisions to sharp-shoot our collective bargaining agreement and issue themselves massive bonuses while furloughing workers have steadily destroyed any ounce of trust employees had left in them.

No trip through bankruptcy court can restore that trust.

All three major unions have now been in contract negotiations for three to nearly five years, with little to show for the time spent and seemingly no end in sight in the employees’ view.

Meanwhile, American’s management complains to the media and anyone else who will listen that the company is unsuccessful because of high labor costs and unproductive workers.

In the Oct. 7 Business Week article, American’s Senior Vice-

President of Human Resources Jeff Brundage is quoted talking about labor costs: “It’s a big brick in our backpack to being competitive in this industry.”

When I first read Brundage’s quote, I winced. Is it any wonder that you have labor problems when the “leader” of the entire workforce is quoted in a national magazine claiming that

American Airlines employees are holding management back from operating a thriving, successful business?

While American has been tied up with labor/management infighting, its competitors have been taking on risks to improve their enterprises.

Continental (now the world’s largest airline since it combined with United) has had a fairly good relationship with its workers and a management known for quality strategic decisions. The other industry power-player, Delta, joined with its workforce to acquire Northwest, filling a key hole in its network. In addition, workers at Delta in two different job functions voted against unionization. My guess is that indicates workers who are happy with the leadership of the airline for the most part.

Could it be that the real correlation to success in the airline business is management’s capability to build a positive working relationship with labor and develop a strategic vision that labor can embrace?

Without an engaged workforce, taking on risk is a difficult task. It becomes easy to justify a risk-averse stance. In the lowmargin, customer-focused airline business, employees can be a force multiplier when it comes to the bottom line.

Airline management have a lot of responsibilities: Raising capital, providing strategic vision, complying with government regulations, marketing the enterprise to potential customers, maximizing return on shareholders’ investments, and of course, leading employees.

But without a highly engaged workforce, the successful execution of those other responsibilities is impossible. The airline business is simply too complex and too customer servicefocused to manage by dictate and without employee buy-in.

Management, the airline board of directors, investors and analysts need to realize that American’s managers must become leaders. They must re-establish a relationship with employees that’s based on trust and commitment. Only then can this airline succeed.

May 2011 7

Flightline

TSA Advanced Imaging

Screening Technology

BY DFW CAPTAIN MICHAEL HOLLAND, AEROMEDICAL COMMITTEE —

DEPUTY CHAIRMAN FOR RADIATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES

In the last few months the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) policy on crew Advanced Imaging Technology

(AIT) security screening has been targeted for action by your

APA leadership. Currently, pilots and f light attendants have been exempted from AIT screening while going to and from work in uniform. Industry has been tasked by the TSA to provide recommendations on how to proceed from here. You will hear more on this from the APA Security Committee in the coming months. It is important for you to understand some of the basics of your radiation exposure, as you are also subject to AIT scanning when commuting and traveling non-rev. This article will examine pilot radiation exposure.

90 percent of your total career radiation exposure is from GCR and less than 10 percent of your total career radiation exposure is from SCR. GCR is fairly constant, but SCR is tremendously variable depending upon solar activity. On rare occasions, the particles emanating from the sun during a coronal mass ejection

(CME) can cause extreme increases in the SCR affecting Earth.

While these extreme occurrences are rare, lesser events occur with more frequency. Only ultraviolet radiation exposure is reduced by f light at night.

Your radiation exposure

Pilots are exposed to both particulate (ionizing: protons, neutrons, etc.) and electromagnetic radiation (some non-ionizing: visible light, radio; some ionizing: X-ray). Ionizing radiation can knock an electron out of the orbit of an atom, thereby changing it; non-ionizing radiation lacks sufficient energy and can’t change an atom. Pilots are exposed to radiation from several sources.

While airborne, these include galactic cosmic radiation (GCR) from space and solar cosmic radiation (SCR) from the sun, but primarily the secondary particles created by the collision of GCR and SCR particles with the atoms of air in our atmosphere.

Additionally, ultraviolet radiation penetrates our windscreens.

While on the ground, exposure comes from many sources including the cosmic sources and secondary particles already identified and others including radon, food, medical imaging, security screening, etc.

AVERAGE EFFECTIVE DOSE BY INDUSTRY

3.5

3

3.07

1 Commercial

Nuclear

Power

2.5

2 Medical

2

1.99

3 Aviation

1.5

3 4 Industry and

Commerce

1

0.5

0

1

.075

2

.087

4

.068 .062

5

Occupation

6

5

6

Education and Research

Gov., DOE,

Military

Adapted from (4-year avg.) NCRP Report 160, Table 7.3, Summary of occupational doses U.S. workers; Nuclear 109,990; Medical 1,957,088; Aviation 177,000; Industry

360,069; Education/Research 351,309; Government/DOE/DOD 265,870.

How much radiation exposure do you get?

On average, pilots are the most highly exposed workforce in the nation, with a greater exposure than nuclear power and medical workers. Some workers in other industries will be exposed to greater individual doses, but airline crewmembers have the greatest average exposure. The graph at right illustrates, in our opinion, a slightly low estimate of airline crew members‘ exposure as found by the National Council on Radiation

Protection and Measurement (NCRP). The NCRP is a scientific group comprised of many disciplines chartered by Congress to advise the nation on radiation issues. Your cosmic radiation exposure at work is directly proportional to the time you spend at cruise. The hourly rate of radiation exposure depends primarily on your altitude, next on your latitude, and finally on the solar conditions existing during your f light. In most cases, more than

How your radiation exposure is measured

You receive a whole body dose of radiation measured in a radiation unit called a sievert (Sv). One sievert is a large amount of radiation in human exposure terms. The sievert is further broken down into millisieverts (mSv or one thousandth of a sievert) and microsieverts (

µ

Sv or one millionth of a sievert). In one flight leg, a pilot’s exposure is measured in microsieverts; in a year’s flying, a pilot’s exposure is measured in millisieverts, perhaps

1-9 mSv. Further, in a career, a pilot’s exposure is measured in millisieverts, perhaps 160 mSv. Some parts of your body are more sensitive to radiation; the sievert measure includes this fact.

Some radiation particles are more problematic than others; the sievert measure includes this fact as well. Most of our airborne exposure is from neutrons. Some TSA security screening uses

X-rays. The formula used to compute the sievert accounts for the difference in these radiation types by assigning a weight of 20 to neutrons and a weight of 1 to X-rays. Obviously, neutron exposure is much more of a problem for us than X-ray exposure.

Flightline

8 May 2011

However, X-rays can be a problem — a medical imaging CAT scan can expose you to a significant amount of X-ray radiation.

Depending on the procedure, you can more than double your yearly occupational exposure in one CAT scan.

TSA Advanced Imaging Technology Screening

The TSA has fielded new AIT machines for passenger and crew screening. Some of these machines use non-ionizing millimeter wave technology (the glass booth machine) and some use ionizing backscatter X-ray radiation technology (the dual solid wall walk-through units that look like a set of blue walk-in freezers set side by side, with a path in between).

Millimeter Wave Unit Backscatter (X-ray) Unit

Millimeter wave technology bounces harmless electromagnetic waves off the body to create a black and white three-dimensional image.*

Backscatter technology projects low level X-ray beams over the body to create a reflection of the body displayed on the monitor.

* Government research is underway studying millimeter wave exposure.

Our analysis of the available information from the TSA,

Rapiscan (the manufacturer of the backscatter X-ray units), the

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and several scientific groups indicates that the amount of X-ray exposure in the backscatter units is very low in a single scan. The manufacturer states: “... a single scan exposure of 0.05 microsieverts (0.05

µ

Sv) per inspection.” 1 The manufacturer acknowledges a small ionizing radiation dose is received during a backscatter X-ray radiation screening. Information from both the TSA’s and the manufacturer’s Web sites indicates that this is the equivalent of about two minutes of f light.

2

An example: A senior international pilot passes through a backscatter X-ray machine on his way to work and is exposed to

.05

µ

Sv of ionizing X-ray radiation. His yearly exposure, assuming the same scenario and a three-trip month (36 backscatter X-ray scans), increases by 1.8

µ

Sv or 72 minutes of cruise exposure.

This results in an increased exposure from screening of 54

µ

Sv or 2,160 minutes in his 30-year career. This exposure is relatively small given his large occupational exposure; however, radiation exposure is cumulative. Given his already large occupational exposure, any additional unnecessary exposure should be avoided in keeping with the principles of radiation dose management.

A pregnant crewmember should not be screened by backscatter

X-ray radiation, as the FAA recommended radiation dose limits for her fetus can be reached in a few months of working.

It is well-known that ionizing radiation can cause cancer and heritable effects. Pilots have perhaps a four times greater risk of skin cancer than the general population. Backscatter X-ray radiation targets the skin for imaging. Other screening methods are available for pilots and have been used in some locations for years. The NCRP has stated in its analysis: “If available, alternate systems not employing ionizing radiation should be considered first.” 3 APA agrees with the NCRP.

Recommendations

• A crewmember should seek advice from a knowledgeable physician before being exposed to ionizing radiation. Note that many physicians are not trained about crew radiation exposure. Little research is available on human exposure to backscatter X-ray.

• Research is needed on the exposure and effects of backscatter

X-ray radiation on pilots/crew.

• Pregnant crewmembers should not be exposed to backscatter

X-ray radiation technology.

• The pilot’s responsibility under radiation management principles requires that he/she take affirmative action to limit his/her ionizing radiation exposure.

• Given the already high exposure of pilots and crew to ionizing radiation and the availability of alternate screening methods, we can’t sanction use of backscatter X-ray radiation screening technology for pilots and crewmembers at this time.

References

1 Rapiscan Systems, “Secure 1000 Single Pose,” “Health and

Safety FAQs,” online at: www.rapiscansystems.com/secure1000/Rapiscan%20Secure%201000-

Health%20and%20Safety-Fact%20Sheet-021811-contact.pdf

2 TSA online at: www.tsa.gov/approach/tech/ait/safety.shtm

3 NCRP, “Presidential Report on Radiation Protection Advice:

Screening of Humans for Security Purposes Using Ionizing

Radiation Scanning Systems,” online at: www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/03/briefing/3987b1_pres-report.pdf

Additional resources

• NCRP report on security screening systems: www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/03/briefing/3987b1_pres-report.pdf

• FAA report on X-ray backscatter security scanners at U.S. airports www.faa.gov/library/reports/medical/fasmb/media/backscatter_research.pdf

• TSA Blog on the subject: blog.tsa.gov/2010/03/advanced-imaging-technology-radiation.html

• News report by Bloomberg : bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=aoG.YbbvnkzU&pos=11

• Millimeter manufacturer product information: www.l-3com.com/products-services/productservice.aspx?type=ps&id=866

• Backscatter X-ray Radiation manufacturer product information: www.rapiscansystems.com/rapiscan-secure-1000-single-pose.html

May 2011 9

Flightline

Can Experience be a Bad Thing?

BY DFW CAPTAIN TOM KACHMAR, PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN

Can experience be a bad thing? Maybe? Sometimes?

I think of my experience f lying airplanes for over 40 years as a tool in the old tool bag. It is just one of the implements that

I use on every f light to ensure my aircraft and whatever is following me in the 600 mph aluminum tube get from point A to B as safely as possible. But is there an added risk involved in relying on just my experience?

When I was in the Navy, I f lew P3 Orion anti-submarine aircraft. It is a military model of the Lockheed Electra from the

1950s. Land-based, four-engine long-range (f lights of more than 12 hours were routine) sub-chasers. We would f ly IFR out to the ADIZ boundary of the United States, cancel IFR and go

VFR from 200’ above the water to 30,000’ and come home.

During the Cold War, this was pretty exciting stuff for a 23-yearold ensign, matching wits with real Commies in the hunt for the

“Red October.”

While on deployment out of NAS Sigonella, Sicily we almost lost one. It was during the middle of the night over the

Mediterranean Sea. One of our crews was on a search-andrescue mission looking for an A7 driver that had ejected and was in the water. Usually while on station we would shut down or

“loiter” the No. 1 engine to save gas. You would think that going

1,000 miles from land and shutting down a perfectly good engine was a bad idea. But I was only an ensign, what did I know? It was our f leet SOP.

The most-junior pilot on the crew was in the left seat, and a very experienced pilot was in the right. The P3 had a f light engineer (sometimes two as it was in this case). There was a young chief petty officer who was a rising star in the community.

This guy was the best of the best, fresh out of the instructor school teaching upcoming f light engineers.

So there they were (got to have this line in any great f lying story), 300 feet above the water, at night, with the No. 1 engine loitered. One of the aft observers (looking out a huge window for the poor A7 guy) says, “Sparks coming out of the #3 engine...

FIRE on #3!”

In the cockpit designed of the 1950s, there wasn’t a lot of thought given to the ergonomics of the layout and the control set up in the cockpit. In the P3, the E (emergency) handles were along the top of the instrument panel, but the gauges did not line up with the corresponding E handle. In other words, the engine gauges for the No. 3 engine were under the No. 4 E handle (Mr.

Murphy, here we come).

The f light engineer scans the engine instruments looking for signs of a fire, looking at the No. 3 engine gauges. He sees nothing, but since the observer identified the fire, he reaches up the line of gauges and pulls the E handle. The only problem was that he pulled the E handle for the No. 4 engine.

So here they are, No. 1 shut down for loiter, No. 2 operating normally, No. 3 on fire, No. 4 inadvertently shut down by

E handle. Now remember, were at 300 feet, at night, with a junior pilot in the left seat. The f light engineer, immediately recognizing his mistake, relies on his experience as an instructor and experience in the simulator, immediately pushed in the

No. 4 E handle followed by a big “whomp” and a report from the aft observer: “FIRE on No. 4, FIRE on No. 4!” They then pulled the No. 4 E handle out for the last time to fight the new fire on the No. 4 engine. We have gone from bad to really bad.

By pushing in the E handle, he immediately added a lot of fuel

(remember no checklists have been accomplished doing things like THROTTLE-IDLE in a procedure). When asked later in the investigation why the f light engineer pushed in the E handle after pulling it, he said, “Well, it worked OK in the simulator.”

This is one of those times where experience can get in the way of good judgment and following proper procedures in accordance with checklists. The pilot group here at AA is also a very experienced group with many pilots on the seniority list for more than 20 years. We have the most professional pilot group in the industry, in my opinion. That being said, have you f lown with any pilot who thinks they have a “better way” of doing a procedure or checklist? Heck yeah — I know I have.

Our experience in seat and fleet should (continued on page 13)

Flightline

10 May 2011

Yes, the A and B Plans

Do Have Annuity Options

BY LGA FIRST OFFICER MICHAEL MACMURDY, PENSION COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN

As an American Airlines pilot, you are probably aware that upon retirement, various annuity options are available from both the A and B Plans. You are also probably aware that very few AA pilots select anything other than a lump sum from either plan. The point of this article is to discuss some of the financial risks we will all face in retirement, and whether or not one of the plan annuities might make sense for you.

A key part of planning for retirement is understanding the risks. The three primary financial risks in retirement are:

• Investment risk — The risk that investments will not perform as well as planned.

• Inflation risk — The risk that inf lation erodes asset values to a greater extent than planned, while your living expenses are increasing.

• Longevity risk — The risk that the participant outlives his assets.

The retirement industry in this country has undergone a seismic shift in the last 25 or so years, moving from a largely defined benefit platform to a defined contribution based system. The general thinking within the retirement industry is that this shift will ultimately lead to the next retirement crisis in the United

States. That is, “tomorrow’s” retiree will rely on a private pension lump sum plus Social Security. Coupled with improving longevity, retirees “outliving their lump sums” is perceived as a crisis in the making.

A Plan

The A Plan annuity is the more straightforward of the two. I’ll initially confine the discussion to the Single Life Annuity, and address some of the other options at the end of this section.

At the most basic level, an annuity and its corresponding lump sum are simply different forms of the same benefit. That is, they are equal in “value,” or said differently, the annuity and the lump sum are actuarial equivalents. However, any sort of conversion between benefit forms requires underlying interest and mortality assumptions: change the assumptions and the adjustment factor changes. We see this every month in our A Plan lump sum factor, as the interest rate assumption is updated monthly.

In general, an annuity is valuable because it helps mitigate two of the primary retirement risks: longevity and investment.

• Longevity risk — As long as the funding source is secure (a topic to which we will return) an annuity provides a source of income for life, regardless of the ups and downs of the economy and the financial markets. That is, one cannot outlive a life annuity.

• Investment risk — The plan sponsor bears the investment risk on the assets that support the annuity. During 2008, not a single retiree’s A Plan monthly annuity benefit was affected by the crash of the financial markets.

Now let’s consider some arguments against the A Plan annuity:

1. The A Plan annuity is fixed for life and therefore does not provide any inf lation protection.

It is true that once an annuity from the A Plan commences, the payment amount is not adjusted for inf lation; however, some background information is in order. Whether we like it or not, the annuity versus lump sum decision is in a sense a call on future interest rates and inf lation. The decision to convert a life annuity to a lump sum at retirement is based on a snapshot of mortality and interest rate assumptions (three months in the past in our case). The interest rate is basically an investment grade corporate bond rate, and ref lects (among other factors) the market’s perception of future inf lation rates. If you take the annuity and future inf lation turns out to be lower than expected, you will “come out ahead,” all else being equal. The opposite is true if future inf lation turns out to be greater than what was the market expectation when you retired. But it may be a little misleading to say the A Plan annuity has no inf lation protection. A more accurate statement would be that a certain inf lation expectation is “priced into” the annuity.

2. If I die early, my heirs will lose out.

This is true to some extent — the A Plan annuity does have a partial refund feature that lasts for the first three to four years of the annuity for the typical participant. There are also optional annuity forms that directly address this concern. However, it is important to remember the opposite case as well — if you experience better-than-expected mortality, you will continue to draw the annuity. One of the advantages of our in-plan annuities is that they are optional, so that individual circumstances (such as above average expected mortality) can be incorporated into the pilot’s decision-making process.

3. What if I take the annuity and sometime later American

Airlines declares bankruptcy?

The threat to the annuity would only (continued on next page)

May 2011 11

Flightline

come from a Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) distress termination, which we all know has happened to several pilot plans within the last 10 years. A complete discussion of the

PBGC benefit calculations is beyond the scope of this article, but it is safe to say that a participant with an annuity that did not exceed the PBGC guarantee would have little to fear from a distress termination. The PBGC guarantee increases with age, and for 2011 is $46,440 for retirement at age 63.

1 This annual annuity figure roughly equates to an AA pilot with a Final

Average Salary of $155,000 and 25 years of credited service.

The annuity option could make sense for pilots with annuity benefits significantly above the PBGC guarantee, but that would require a more detailed analysis. Very brief ly, if you are retiring relatively “young (but at least age 53) and senior,” the timing of a potential bankruptcy filing and your date of retirement would become very important. This is because the PBGC PC-3 calculation “rolls” the participant back three years in time. This means (in the worst case) your benefit could be reduced due to loss of three years of credited service, and by the imposition of up to three years of early retirement actuarial reductions.

The risk to a pilot in this situation would decrease significantly during the first three years of retirement, as the impact of the

“three-year roll-back” begins to decrease steadily upon retirement.

If a pilot had been retired and drawing an A Plan annuity for at least three years when bankruptcy was declared, the “three-year roll-back” would have no effect, so any loss incurred would be determined by the funded level in Priority Category 3.

2

4. Why shouldn’t I take my lump sum and just buy a commercial annuity, and not have to worry about the PBGC?

This is certainly an option, although annuities are inherently complex and you may find it difficult to compare commercial annuities due to differing features. Also the price of almost any commercial annuity will ref lect:

• The insurance company’s costs and profit margin

• Sales commission

• State-mandated reserves

• A provision for adverse deviation

• A biased mortality table (i.e. designed for people with above-average longevity)

The A Plan annuity has none of these. As stated earlier, it is simply one of several benefit forms that are equivalent in value (for a given interest and mortality assumption). Therefore, the payments from the A Plan would be larger for a given “purchase price” versus almost any comparable commercial annuity.

Up to this point, I have only addressed the

Single Life Annuity. Both the A and B Plans have

Joint and Survivor, and Guaranteed Period options (a Guaranteed Period annuity is a life annuity, with the protection that it will continue to pay out for a preset period should the annuitant die within the specified period). There are several other less common annuity forms available as well.

B Plan

I will say at the outset that the B Plan annuity is a bit of a conundrum, in that it is a great deal for the annuitant, but that it may not be suitable for many of us.

The basics of the B Plan annuity are:

• The B Plan annuity factors are fixed by the plan document

(so unlike the A Plan lump sum factors, they do not change).

• The underlying interest and mortality assumptions are very favorable to the annuitant — the mortality assumption alone adds about 15 percent of value.

• The B Plan annuity has the same advantages over commercial annuities that the A Plan annuity has, as described above.

• The B Plan annuity is calculated in units, and the dollar amount of the monthly payment resets twice a year based on the current unit value. This means the monthly payment can and does vary significantly from one six-month period to the next.

I think we all know that each year our existing units are increased by six percent, and the unit value is decreased correspondingly so that the account value is not affected. The reason for what seems to be a meaningless accounting exercise is the annuity. Because the B Plan annuity is fixed in units, the net result is that the monthly payment increases when the B Plan returns more than about six percent in a given year, and decreases when the B Plan returns less than about six percent.

The following chart illustrates this effect for a pilot who retired in January 1991 and took his B Plan benefit as a Single Life

Annuity. If his monthly “payment” in units was 100 units, in

Annuity Unit Values

Flightline

12 May 2011

dollars his initial monthly payment would have been about

$5,684. If this pilot was still alive in December 2010, his monthly payment of 100 units would equate to $8,109. It is important to understand that ALL of the increase from $5,684 to $8,109 is “gain.” This is because a constant annuity of $5,684 would already ref lect the generous assumptions underlying the

B Plan annuity. The unit values driving the value of this pilot’s annuity payments over the 20 years he has been retired are shown in the chart to the left (as always, past performance should not be considered a reliable indicator of future performance).

This chart also illustrates a major issue with the B Plan annuity

— high volatility. Since this annuity is normally taken for life, this level of volatility may be unsuitable when the participant is at an advanced age, especially if the B Plan comprises a significant portion of one’s assets upon retirement. Of course, this volatility must be viewed in the context of the other very favorable features of the B Plan annuity.

The B Plan annuity is available in all the forms the A Plan annuity is, except the Social Security leveling option. It contains a refund feature conceptually similar (although of greater duration) to that of the A Plan annuity, should the annuitant die relatively soon after benefit commencement.

Just to be clear, I am not telling anyone they should take one of the in-plan annuities. Both the A Plan and B Plan annuities have strengths and weaknesses, just as the lump sum option does.

As always, it comes down to understanding the characteristics of different investment options, viewed in the context of your personal financial situation.

1 To be a little more precise, the PC-4 guarantee is based on the participant’s age at the later of benefit commencement or bankruptcy filing.

2 Consider a pilot who retires at age 60 with 30 years of service and a final average salary of $220,000. If AA were to declare bankruptcy one year later, and the A Plan were to subsequently undergo a distress termination (but sufficiently well-funded to pay full PC-3 benefits) as a rough approximation, this pilot might lose 26 percent of his annuity benefit due to the three-year roll-back. If the bankruptcy filing was instead two years after his retirement, his expected loss would drop to around 16 percent. His annuity would not suffer any reduction if the bankruptcy filing was three years or more subsequent to his retirement

(assuming fully funded at the PC-3 level). If the PC-3 funded level was less than 100 percent, these loss figures would be larger.

Because the PC-3 funded level in termination would be determined by the interaction of large number of factors, and because of recent statutory changes with respect to defined benefit plan funding, it is not possible to provide any sort of assurance as to what the PC-3 funded level might be in a distress termination. However, for many AA pilots, the

PC-3 funded level would not have any effect on their PGBC benefit.

As a rough approximation the PC-3 funded level becomes significant for pilots with accrued annuity benefits larger than about $75,000.

Warning: PBGC benefit calculations are complex and professional assistance is strongly encouraged when potential scenarios are analyzed.

Results can vary widely by individual pilot, as there are many interacting variables. The above figures should only be considered as very general guidelines.

Can Experience be a Bad Thing?

(continued from page 10) not be used to replace or modify AA SOPs, procedures or regulations. Add a dose of rushing to comply with an emergency, or even a normal set of procedures, and things get ugly fast. Our experience should be used to enhance, supplement or make the rules, etc. safer, and not to replace them. When the weather radar shows no returns but you are staring at a big black sky of boiling clouds, that’s when your experience should affect your judgment and lead you to follow the safest, smoothest course for our crew and passengers. Experience is the best teacher, but we cannot replace SOP with just our own set of personal experiences. Of course, in an emergency, the pilot in command may do whatever is necessary to safely complete the f light. Absent any written rules or policy, you’ve got to go with what you have.

So what is the rest of the story? Order and calm was finally restored. They pulled the No. 4 E handle, left it out this time and diverted to an airport on two of the four engines. So what were the pilots doing during this whole fiasco? The senior pilot in the right seat was just an observer to this whole mess. The pilot in the left seat, the junior guy, was the only one who kept his cool.

He stayed on the gauges, f lew the aircraft at the L/D max speed, which the f light engineer calculated constantly during the f light while engines were loitered, while descending to the ocean surface in a single-engine descent to maintain airspeed on only the No. 2 engine. They got the No. 1 engine that was loitered from the beginning restarted at around 100 feet above the water.

Unfortunately, the A7 pilot was never recovered.

The guy with the least experience had the lives of that whole crew in his hands. He did the right thing. When you don’t have a lot of experience, you have to rely on your training, policies and procedures to keep you safe, and that’s what he did.

Don’t let your experience get you into trouble. Use all of the tools in your possession — training, SOP, rules, policies, checklists, procedures and experience to safely take care of our passengers and crew, demonstrating to all that we are the most professional pilot group out there.

As the boss says, f ly aggressively safe!

Flightline

May 2011 13

Pilots and Acute Stress Disorders

BY DFW FIRST OFFICER CHARLIE CURRERI, DEPUTY CHAIRMAN OF EAP

Editor’s Note: FO Curreri is a licensed professional counselor in Arlington, Texas

During the past several months, I have received calls from fellow aviators concerning events in their lives, past or present, that were causing them considerable angst and disrupting their personal relationships.

In one case, a 55-year-old pilot recalled being involved in a tragic car accident several years ago, resulting in the death of several people. This accident, unbeknownst to me, was causing significant interpersonal difficulties in this person’s life. The relationship with their spouse was deteriorating, and they couldn’t sleep due to f lashback nightmares. This pilot was was constantly irritable, easily angered and experiencing unexplainable mild headaches over the past few months. As the relational difficulties worsened, the pilot was referred to APA/EAP through APA

Professional Standards in order to address some complaints made about the pilot by concerned crewmembers. After spending some time talking with the pilot about the cockpit issues, a further assessment — including a life history inventory — was given. It became clear that the tragic accident the pilot encountered years ago was resurfacing. The pilot no longer possessed the psychological coping mechanisms to overcome the haunting memories of the tragic accident.

This article will address the underlying issues encompassing a pilot’s outward behavior and possibly shed light on maladaptive human behavior as a result of acute stress disorder (ASD).

All of us have experienced some type of trauma in our lives.

The list, although not exhaustive, includes: physical trauma

(death, divorce, war, accidents, tragedy, etc.) and psychological trauma (sexual abuse, rape, domestic abuse, etc.), and in other cases, a flight incident or flight accident. Regardless of the source, we are deeply impacted by these events, personal or aviation related, whether we admit it or not. Of course, different people will react differently to similar events. One person may experience an event as traumatic, while another person might not suffer trauma as a result of the same event. In other words, not all people who experience a potentially traumatic event will actually become psychologically traumatized.

For many people, especially pilots, talking about personal stress in an intimate and emotional manner is not conducive to maintaining the illusion of control. During these traumatic events, our psyches go into “protect” mode, creating a safe place for us to navigate away the painful and traumatizing experience.

This psychological defense serves a useful purpose in the beginning stages of acute stress. However, over the course of time, the defense mechanisms begin to fall apart. At this point, many people begin manifesting the many signs of acute stress disorder.

According to the American Psychological Diagnostic Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the essential feature of ASD is the development of characteristic anxiety, dissociative and other symptoms that occur within one month after exposure to an extreme traumatic stressor.

Distressing dissociative symptoms are common in the person with ASD, including depersonalization, de-realization or dissociative amnesia. Anxiety, irritability and depression are also common in people who have acute stress disorder. People with ASD have a diminished ability to experience pleasure.

There may be problems falling or staying asleep. A person with

ASD will avoid any reminders of the trauma, but re-experience the event in dreams, nightmares or painful memories.

The disorder features persist for longer than 30 days, which distinguishes it from the briefer acute stress disorder. These persisting post-traumatic stress symptoms cause significant disruptions of one or more important areas of life function.

Symptoms of ASD fall into three main categories: First, repeated “reliving” of the event , which disturbs day-to-day activity.

These include f lashback episodes, where the event seems to be happening again and again. People also experience recurrent distressing memories, repeated dreams and physical reactions to situations that remind you of the traumatic event. Second, there is a strong avoidance of the event . These include: emotional

“numbing,” or feeling as though you don’t care about anything; feelings of detachment; inability to remember important aspects of the trauma; lack of interest in normal activities; less expression of moods; staying away from places, people or objects that remind you of the event; and a sense of having no future.

Finally, ASD symptoms include increased arousal . These include: difficulty concentrating; exaggerated response to things that startle you; excess awareness (hyper-vigilance); irritability or outbursts of anger; and sleeping difficulties.

You also might feel a sense of guilt about the event (including

“survivor guilt”), and experience the following symptoms, which are typical of anxiety, stress and tension: agitation, excitability, dizziness, feeling your heart beat in your chest (palpitations), headaches and paleness.

What should you do if the above issues are apparent in your life? First, recognize that early treatment is better . Symptoms of ASD can and may get worse. Dealing with them now might

Flightline

14 May 2011

help stop them from getting worse in the future. Finding out more about what treatments work, where to look for help, and what kind of questions to ask can make it easier to get help and lead to better outcomes. Second, recognize that ASD symptoms can drastically change family life . You may find that you pull away from loved ones, are not able to get along with people, or that you are angry or even violent. Getting help for ASD can help improve your family life. Finally, recognize that ASD symptoms can worsen physical health problems. For example, some studies have shown a relationship between ASD and heart trouble. By getting help with ASD you could also improve your physical health.

Historically speaking, pilots do not typically recognize or deal with these issues by seeking professional help. This reluctance to seek help is related to high-functioning personality types who perceive themselves as always being confident, independent and most importantly, in control.

Another major obstacle to seeking help is the fear of having to report any counseling or treatment to the Federal Aviation

Administration and the risk of permanently losing a medical certificate and perhaps a career. This fear is usually unjustified in the vast majority of cases. Pilots are now encouraged to identify and seek help for stress and symptoms of poor emotional health. The FAA’s latest policy allows pilots diagnosed with mild to moderate depression to f ly while taking antidepressants, provided that they can demonstrate that they have been treated for at least 12 months. This new policy will allow pilots to seek professional treatment instead of self-medicating or avoiding a diagnosis.

Who should I call?

If you want to talk to someone about acute stress and possible treatment options, there are many resources available to you:

• The APA Aeromedical Committee: Call the committee hotline at 1.800.323.1470, ext. 3043. This voicemail is monitored throughout the day by trained APA volunteers for your benefit. Please leave a detailed message that includes phone numbers where we can contact you and a member of the Aeromedical Committee will return your call as soon as possible.

• The APA/AA Employee Assistance Program (EAP/APA):

Charlie Curreri, 817.658.9290 or AA/EAP Clark Vinson,

817.963.1155.

APA Government Affairs has developed a “grassroots” lobbying effort that sends trained APA volunteers to legislators’ offices in their home districts to promote APA issues. Thanks to the following volunteers who have stepped up so far:

FO William Read, MIA

FO Brian Smith, MIA

CA Greg Kunasek, DFW

CA Jeff Rich, DFW

FO Ken Goins, DFW

FO Jeff Hefley, STL

FO Dave Culbertson, ORD

CA Dean Davis, ORD

CA Steve Hart, LAX

FO Bo Wooden, LAX

FO Brian Sullivan, SFO

FO Thomas Copeland, LGA

FO Robert Schroer, DFW

CA Don Cruikshank, DCA

FO Ken Wuttke, ORD

CA Adam Hughes, LGA

CA Rick Burrus, MIA

FO Curtis Chastain, DFW

FO Dan Conway, BOS

FO Elaine Magor, LAX

FO Jon Stevens, ORD

APA will continue to recruit additional volunteers for this important job. If you are interested in being considered for this program, please contact Government Affairs member First Officer Mike Margiotta at fos80@comcast.net

. Previous experience in this area is desired, but not required.

May 2011 15

Flightline

Shutting down an engine changes everything

BY SFO FIRST OFFICER RICHARD VOJVODA, COMMUNICATIONS MEMBER

We’ve all spent countless hours cruising in smooth air. Those hours, marked by familiar routines and long stretches with the seat belt sign turned off, can leave us complacent or, worse, overconfident.

But so often in aviation, our well-honed skills are put to the test suddenly and without warning.

On July 13, 2010, American Airlines Flight 61 was cruising smoothly above the clouds at 30,000 feet just north of the

Canadian border with Captain Larry Schexnaildre at the controls and First Officer Jim Morrison in the right seat. Three hours earlier, the aircraft had lifted off from Dallas/Fort Worth with a gross weight of 648,000 pounds and now weighed just under

600,000 pounds. So far, the f light had been uneventful and was expected to remain so, giving Captain Schexnaildre the confidence to have the seat belt sign switched off.

A beeping alert brought the two aviators’ attention to the upper EICAS message: “Low Engine Oil Pressure, Left Engine.”

Both pilots looked at the upper EICAS and then at each other.

The aviators knew that they needed to act quickly and accurately to prevent the further loss of oil pressure and quantity from jeopardizing their aircraft and their 220 passengers.

With First Officer Morrison confirming, Captain Larry

Schexnaildre began performing the appropriate immediate action items and selected the left AT arm switch to off, then retarded the thrust lever of the stricken engine to idle. The Low

Engine Oil Pressure checklist, in view on the lower EICAS, further instructed the pilots to recheck the ENG OIL PRESS message. It remained displayed and they were then guided, by step 5, to confirm and cut off the left fuel control switch.

On each f light, our every move is scrutinized. Perfection is the given standard. The decision to shut down an engine during an ETOPS f light is not to be taken lightly. By selecting the fuel control switch to cut off, these pilots would critically alter their f light and their aircraft’s capabilities. On Captain Schexnaildre’s command, First Officer Morrison placed his left hand on the left fuel control switch and selected the switch to cut off, thereby shutting down the engine.

In a span of mere minutes, these aviation professionals went from smoothly cruising at 30,000 feet en route to Narita to being at the helm of a crippled Boeing 777 aircraft with 220 passengers’ fates in their hands. They quickly decided to declare an emergency and divert to Calgary, a familiar field, 120 nm ahead.

Captain Schexnaildre guided the jet into the descent for an emergency landing in Calgary and assumed responsibility for the radios while First Officer Morrison continued the Left Engine

Low Oil Pressure Low checklist.

With the aircraft 135,000 pounds over the maximum landing weight, Captain Schnexaildre immediately coordinated with

ATC for clearance to begin dumping fuel. With ATC’s consent, he then instructed First Officer Morrison to pull up the Fuel

Jettison checklist and commence the fuel dump. Soon after they left their cruise altitude, First Officer Morrison armed the Fuel

Jettison Arm switch, reached up, lifted the guard and pressed the jettison button. They would continue to dump fuel until the aircraft reached 5,000 feet and some 100,000 pounds of fuel had been jettisoned.

With both the fuel dump and the Left Engine Oil Pressure checklists nearly complete, First Officer Morrison turned his attention to communicating with ATC and obtaining the weather and runway conditions at Calgary. The airport reported an overcast cloud cover at 3,000 feet with wind blowing from

260° at 18 knots gusting to 27 knots.

Satisfied that they had done all they could to ensure the aircraft’s safety, Captain Schexnaildre then briefed the f light attendants and instructed them to perform the 30-second emergency landing brief. He also addressed the passengers, informing them of the situation and his intention to land the jet in just a few minutes at Calgary.

Pilots Rob Shore and Mick Koehler returned to the cockpit from their crew rest seats. Captain Schexnaildre instructed them to review the landing distance and single-engine approach and go-around capability of their overweight jet. They determined that two runways at Calgary could support their Boeing 777 aircraft. One, runway 28, is 8,000 feet long and the other, runway

34, is 12,675 feet. Captain Schexnaildre had already decided what runway he was comfortable with. But he wanted the consensus of the three other experienced professionals in his cockpit. The aircraft was capable of landing on both (continued on page 18)

Flightline

16 May 2011

APA Launches New Alliedpilots.org

Members’ Home Page

The APA Information Technology Department and APA Communications recently launched a redesigned home page for the union’s alliedpilots.org Web site. It features an updated appearance consistent with the recently redesigned public home page, as well as much-improved navigation and organization of key functions.

1

Along the top of the home page, “pull-down” type menus give members access to some of the most important union resources:

• Contact APA.

Here you’ll find contact information for

APA staff, APA committees and APA leaders.

• Bidding/Scheduling.

Use this menu to access bid sheets, as well as the trip trade, vacation trade and mutual base exchange systems.

• Benefits/Services.

Under this menu, you’ll find information and forms for APA benefits programs, as well as resources for furloughees and those on military leave.

• Contract Resources.

This menu contains everything related to the AA-APA collective bargaining agreement, including a link to APANegotiations.com

for the latest information on Section 6 negotiations. You can also use this link to send questions to APA’s Contract Administrators.

• Domiciles.

Each domicile’s home page is listed under this menu.

• Committees.

You’ll find each APA committee’s own page under this menu.

2

On the left-hand side of the page, you’ll find links that help you quickly access the vast amount of information available on alliedpilots.org:

• Hot Topics.

Click here to keep up-to-date on important issues.

• APA News.

Find archives of the weekly APA News Digest , as well as past APA Information Hotlines, press releases, issues of Flightline and Turning Final and APA Communications videos.

• Calendar of Events.

Click here to find information on upcoming union events.

• APA Governance.

Click here to access the APA Constitution and Bylaws, the APA Policy Manual, as well as resolutions and meeting minutes.

• From the APA President’s Desk.

This link will take you to a compilation of correspondence issued by or to the

APA president.

3

In the center of the page, a large graphic will highlight current important issues or the latest APA video production.

4

On the top right-hand side of the page, the “Account Login” box includes your personal information, as well as access to the

2

3

1

5

4

6

Challenge & Response forum and your Family Awareness contact information. Please double-check that your e-mail address on file with APA is correct and the address that you prefer. All APA members will need to register a new password the first time they log on to the new site, and the registration process will start with a confirmation e-mail to the address on file.

5

Below the main graphic, the “National and Domicile E-mails” section lists the most recent e-mails from both APA headquarters and individual domiciles. The “Industry News” section highlights airline industry news articles specially selected by union staff members.

6

Below the Account Login box are links that give members several ways to interact with the union:

• In Case of Emergency.

Click here to view APA emergency contact information, steps to take after an accident/incident, as well as a link to the Accident/Incident Contacts International Directory.

• Soundoff.

Click here to send a “Soundoff” message to your elected APA leaders, including the APA Board of Directors and National Officers.

(continued on next page)

Flightline

May 2011 17

• Mobile Sabre.

Use this link to quickly access DECS.

• Member Lookup.

Click here to look up the contact information of APA member pilots.

• ASAP and P2 Reporting.

Submit an ASAP or P2 report through this link.

• File an Observer Report.

See something wrong out on the line? Click on this link to file an Observer Report. YOU are the eyes and ears of our union!

• Debriefs.

Click here to submit jumpseat, training, hotel, security and FFDO professional standards debriefs.

• Pilots Helping Pilots.

Click on this link to step up and add your talents to the pool of APA volunteers that keep the union running. You can also use this link to contribute to the APA Scholarship Fund and the APA Political Action

Committee Fund.