Portraits of the Sun: Violence, Gender, and Nation in the Art of

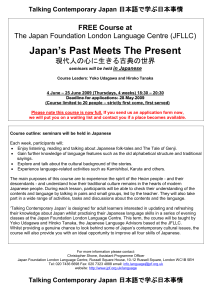

advertisement