240 Years of Ranching Historical Research, Field Surveys, Oral

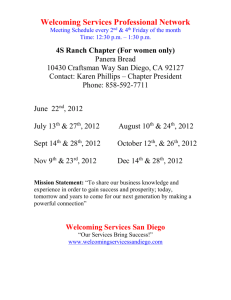

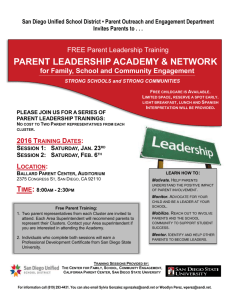

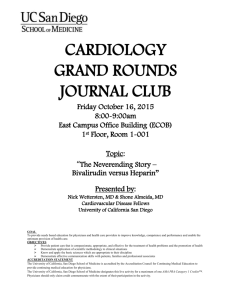

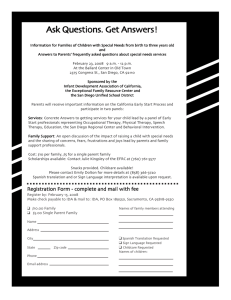

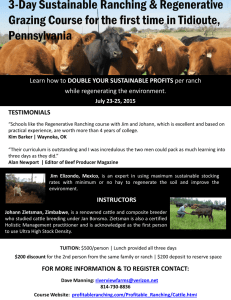

advertisement