Inpatriates Archivo

advertisement

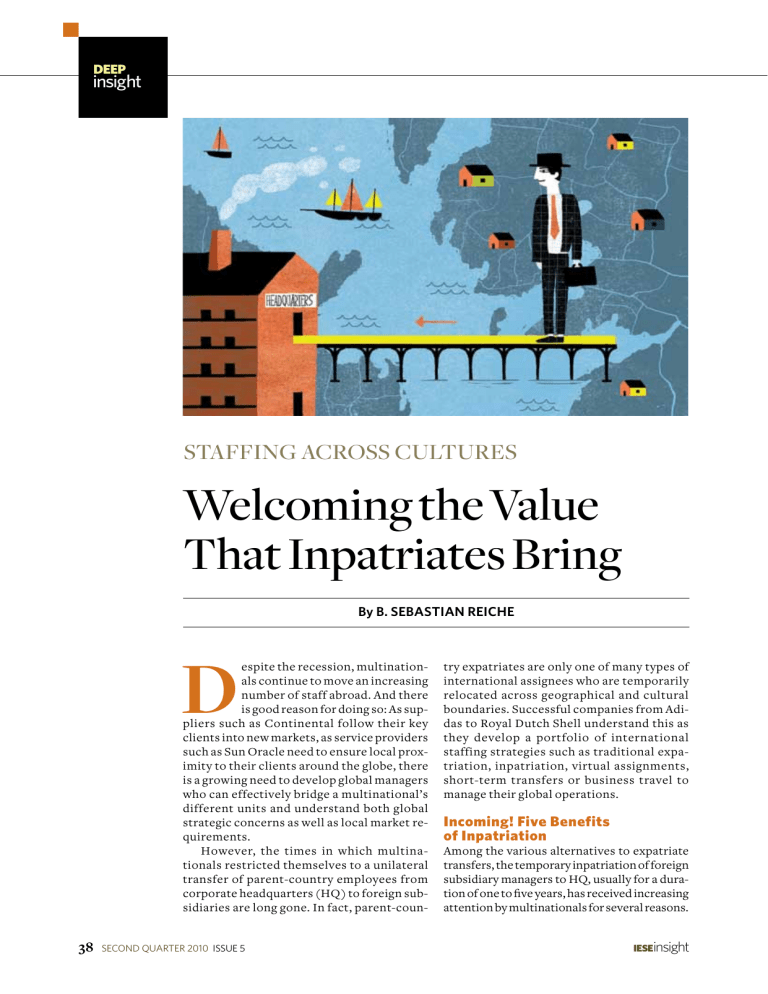

deep insight STAFFING ACROSS CULTURES Welcoming the Value That Inpatriates Bring By B. SEBASTIAN REICHE D espite the recession, multinationals continue to move an increasing number of staff abroad. And there is good reason for doing so: As suppliers such as Continental follow their key clients into new markets, as service providers such as Sun Oracle need to ensure local proximity to their clients around the globe, there is a growing need to develop global managers who can effectively bridge a multinational’s different units and understand both global strategic concerns as well as local market requirements. However, the times in which multinationals restricted themselves to a unilateral transfer of parent-country employees from corporate headquarters (HQ) to foreign subsidiaries are long gone. In fact, parent-coun- 38 second QUARTER 2010 issue 5 try expatriates are only one of many types of international assignees who are temporarily relocated across geographical and cultural boundaries. Successful companies from Adidas to Royal Dutch Shell understand this as they develop a portfolio of international staffing strategies such as traditional expatriation, inpatriation, virtual assignments, short-term transfers or business travel to manage their global operations. Incoming! Five Benefits of Inpatriation Among the various alternatives to expatriate transfers, the temporary inpatriation of foreign subsidiary managers to HQ, usually for a duration of one to five years, has received increasing attention by multinationals for several reasons. ieseinsight the power of GLOBAL Welcoming the Value That Inpatriates Bring THINKING First, as multinationals are trying to contain their rising costs for international staffing, the inpatriation of foreign staff is often a cheaper alternative than relocating parentcountry employees, especially in the case of inpatriates from developing and emerging economies, where the salary level is relatively lower. Second, multinationals are facing increasing barriers to international mobility among their parent-country employees, as dual-career couples are less willing to relocate to another country at the expense of the partner’s career. Inpatriates, who tend to be younger, often have fewer family constraints, and given the alternative of staying put in a small country unit, they view an assignment to HQ as a significant career opportunity that is hard to refuse. Third, the inpatriation of foreign staff is often the only way for HQ to gain sufficient local knowledge for entering and developing executive summary The temporary inpatriation of foreign subsidiary managers to HQ is on the rise: it’s cheaper than expatriating staff, it’s often the best way to gain local knowledge fast, it wins over local workforces and it expands the prospects for staff development and promotion. However, the author’s various studies of subsidiary staff relocated to the headquarters of multinationals reveal that for inpatriation to work, both the individual inpatriate and the multinational need to understand the key factors that make or break these special arrangements. If the inpatriate is able to build good social capital, is mentored by HQ staff and can speak the language of the HQ country, then both sides stand to reap mutual benefits from the exchange. If there is an ieseinsight ethnocentric attitude among HQ staff, a large distance between the inpatriate’s home culture and the HQ country culture, and no real thought given to what happens to the inpatriate when the assignment is done, then the transfer is bound to fall flat. The author recommends that multinationals carefully manage inpatriation at every stage of the process – from selection and preparation, to relocation and reintegration – in order to minimize turnover tendencies and capitalize on the real value that these younger managers bring. Managing this process well can help MNCs to develop strong leaders who can effectively bridge different units and understand both global strategic concerns as well as local market requirements, which is so vital today. new markets. For example, when Lufthansa decided to expand its cargo business from Europe to China and Taiwan, instead of sending a German expatriate to those regions, the company inpatriated a Hong Kong Chinese who knew the local market and could quickly push the business in that direction. Fourth, inpatriation serves as an important developmental tool whose benefits are twofold. By absorbing the corporate culture and learning the management practices of HQ, inpatriates are better prepared to assume future management responsibilities in local or regional offices. This, in turn, reduces the perception among local staff that there is a glass ceiling, especially in strategic units whose top management positions are mainly staffed by expatriates. These factors can help to retain key talent in the long term. In fact, in a study among Western multinationals operating in Singapore, I found the lack of such international career prospects to be one key determinant of turnover among local subsidiary staff. Finally, providing development opportunities beyond the local unit also helps to gain support from the local workforce in situations of organizational change. Consider the case of an Australian franchisee of a large U.S. soft drinks producer that set up operations in Vienna. When the company found itself with a strategic opportunity to expand into Eastern Europe, it was hampered by its failure to prepare local staff sufficiently for international transfers. When the decision was made to acquire operations across Eastern Europe, the local Viennese staff was unwilling to relocate, which required the company to transfer more staff from Australian HQ. This resulted in greater staffing costs, and strained human resources and career planning at HQ for several years. Despite these many benefits, the process of inpatriation is often not as formalized or structured as the expatriation of parentcountry employees, as one U.S. inpatriate found out: “As an inpatriate, you are still considered exotic. The processes for being transferred from HQ are very clear, but as an inpatriate, you have to manage a lot on your own.” What’s more, given the relative recency of the inpatriate phenomenon, the key drivissue 5 second QUARTER 2010 39 the power of GLOBAL Welcoming the Value That Inpatriates Bring THINKING Inpatriates face greater adjustment challenges compared with expatriates. Not only do they have to adjust to the national culture, but they also need to be socialized into HQ culture. ers for the success of inpatriates are not well understood. To address this gap and examine inpatriate groups in more detail, I conducted one of the first large-scale inpatriate studies, which included interviews with inpatriates and HR managers, as well as quantitative data from 286 inpatriates, collected at three different points in time over a period of four years. These inpatriates were relocated to the headquarters of 10 German multinationals from a diverse range of industries. I complement these findings with additional experiences that I obtained from dealing with and studying Western multinationals operating in Australia and Singapore. Who Are the Inpatriates? Who is this new breed of worker who bridges geographical and cultural boundaries for multinationals? And how do these workers about the author B. Sebastian Reiche is assistant professor in the Department of Managing People in Organizations at IESE. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of Melbourne, Australia. His research focuses on how actors access, maintain and leverage knowledge resources, primarily from a multinational and cross-cultural perspective. His research has appeared in the Best Paper Proceedings of the Academy of Management and Academy of International Business and is published in scholarly journals such as Journal of International Business Studies, 40 second QUARTER 2010 issue 5 International Journal of Human Resource Management, International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management and International Business Review. He is a member of the editorial board of the International Journal of CrossCultural Management and a permanent chair of the annual EIASM Workshop on International Strategy and CrossCultural Management. He has held teaching appointments at the University of Melbourne, Australia, and Nile University, Egypt, and has been involved in various consulting activities in Germany (his country of origin) and Singapore. differ from traditional parent-country expatriates? Put simply, an inpatriate assignment is merely an alternative form of HQ /subsidiary linkage going in the opposite direction from an expatriate assignment. However, the differences between the two groups are much more pronounced (see Figure 1). Inpatriates tend to be relatively younger employees or middle managers who are transferred to a multinational’s HQ, often for developmental purposes. Their role is, therefore, much less as a specific corporate agent, more one of global potential. The inpatriates in my study were an average of 37 years old. They came from 45 different cultures, covering all major regions of the world. Among the 286 inpatriates, around 60 percent came from developed countries in North America, Western Europe and the Pacific Rim, while the remaining 40 percent came from developing and emerging economies. In terms of national origin, inpatriates tend to be much more diverse than their expatriate cohorts, who largely originate from developed economies, which continue to host the highest number of multinationals. Not all inpatriates had the clear objective of returning to their home subsidiary upon completion of their transfer, possibly to replace existing parent-country expatriates. Some continued to stay at HQ on a more permanent basis, acting as links between HQ and foreign operations. Others accepted subsequent relocations to other country units, often within the home region of the inpatriate. This finding supports the growing trend of treating international transfers, not as isolated incidents, but as part of an international career path. Another difference between the two groups of assignees is their status in the host unit. Expatriates carry status as HQ representatives. Inpatriates, who come from the ieseinsight the power of GLOBAL Welcoming the Value That Inpatriates Bring THINKING A New Breed of Worker FIGURE 1 HOW DO INPATRIATES DIFFER FROM TRADITIONAL EXPATRIATES? Inpatriate Expatriate Age Younger (average age: 37) Senior National origin All regions of the world Mainly developed economies Perceived status Peripheral HQ agent Level of influence Low High Adjustment challenges Corporate culture & national culture National culture Staffing philosophy Diverse Ethnocentric periphery of the multinational, first need to earn respect and credibility before gaining comparable status, especially if they are from developing economies or relatively small foreign operations. Similarly, regarding their level of influence, expatriates usually possess an explicit mandate to implement HQ procedures and practices in foreign subsidiaries, whereas inpatriates’ objectives are often less tangible, requiring that they learn HQ knowledge and share subsidiary knowledge. Inpatriates also face greater adjustment challenges compared with expatriates. In fact, inpatriates not only have to adjust to the national culture, but they also need to be socialized into HQ corporate culture. As a Singaporean inpatriate remarked, “It was to be expected that the German culture would be very different for me (…but) what I did not foresee was how different HQ looks ieseinsight from afar. And I’d say that it has been more important for me to come to terms with the culture in HQ than with the German culture.” This is very different from expatriates, who are expected to impose elements of HQ corporate culture upon the subsidiary they are sent to. A final distinction is that the use of inpatriates increases the cultural diversity and multicultural composition of staff at HQ. Integrating inpatriates into HQ management teams, even temporarily, means that a higher share of employees with diverse cultural backgrounds will be collaborating directly. The use of expatriates, on the other hand, reflects an ethnocentric, HQ-based view toward international staffing, and expatriates generally continue to coordinate with their own HQ management teams. In this regard, the transfer of inpatriates to HQ has the added benefit of exposing HQ staff to international perspectives. Facilitators to Inpatriate Success While inpatriation has certain cost advantages over traditional expatriate assignments, any international relocation entails a heavy investment with an uncertain future return. This is especially true for inpatriate transfers, given their developmental nature and intrinsic long-term benefits. For multinationals to get the most out of this investment, issue 5 second QUARTER 2010 41 the power of GLOBAL Welcoming the Value That Inpatriates Bring THINKING A multinational should strive for inpatriates’ long-term retention, so that they can continue to link HQ with subsidiaries, and eventually replace expatriate staff in the local or regional office. understanding the key drivers and barriers to success is critical. In my study of inpatriates at German multinationals, I was interested in two different but interrelated dimensions of inpatriate success. First, since inpatriates are expected to learn the HQ corporate culture and HQ management practices while also sharing their expertise of the local subsidiary context, knowledge exchange between inpatriates and HQ staff must be important. Second, given the developmental nature of inpatriate transfers and inpatriates’ understanding of both HQ and subsidiary contexts, a multinational should strive for their long-term retention, so that inpatriates can continue to link HQ with subsidiaries, and eventually replace expatriate staff in the local or regional office. Based on my findings, I identified three key factors that facilitate the success of inpatriate transfers. social capital . Social capital appears to be the most important factor for both inpatriates’ knowledge sharing and their retention. Social capital is a concept that goes beyond mere social relationships; it includes trust and shared identity. Building social relationships enables inpatriates to locate those HQ employees who can benefit the most from their expertise of the subsidiary context, and enables them to access relevant HQ-specific information for themselves. For example, a Thai inpatriate used social relationships with a higher-level colleague at HQ to obtain the help she needed to compile a project report in accordance with HQ standards. At the same time, a large part of the knowledge that inpatriates exchange with HQ staff is culturally imprinted. It is not easy to explain how to deal with local government agencies in China if the other person has no knowledge of appropriate business conduct in China. In this case, a trusting relationship 42 second QUARTER 2010 issue 5 will help the inpatriate and the HQ counterpart to learn about each other’s different frames of reference and to interpret the meaning of the knowledge that is shared. These social relationships and the trust developed with HQ staff can be maintained even after the inpatriate transfer has been completed; in fact, they are instrumental for inpatriates to access HQ knowledge relevant for their new positions. Trust also makes it more likely that the inpatriate will see positive career opportunities and continue to stay with the company upon completion of the transfer. Trusting relationships with HQ staff provide useful career support and endorsement. Another aspect of social capital is identification with HQ. Identification helps inpatriates learn about and become socialized into HQ corporate culture, while increasing the likelihood that inpatriates will see career opportunities and remain with the multinational after their transfer ends. Identification enables inpatriates to understand what is required of them, in order to be successful and get promoted in the company. mentoring . A second factor that contributes to the success of inpatriate assignments is the existence of mentoring. HQ mentors are able to open doors for inpatriates and essentially share their own social capital with them. Furthermore, the fact that a mentor backs the inpatriate allows the latter to receive attention from other HQ colleagues and have his or her qualifications acknowledged by seniors. This is particularly relevant for inpatriates who are newcomers from different cultures, because their qualities and skills may be more difficult to assess by HQ staff due to cross-national differences in educational and organizational promotion systems. Finally, a HQ mentor can provide access to resources, such as important information about existing power structures and inforieseinsight the power of GLOBAL THINKING Welcoming the Value That Inpatriates Bring Ethnocentric attitudes among HQ staff inhibited inpatriates’ ability to identify with HQ. This made it more difficult for them to engage in knowledge exchanges, and less likely they would remain with the company. mal communication channels in HQ. As HQ colleagues become more forthcoming with information and inpatriates get to know additional sources of information, they enlarge their social capital and knowledge exchanges. Mentoring is a crucial driver of this whole process. This is especially important for shorter assignments, when inpatriates have less time to develop relationships. language proficiency . The third facilitator is the inpatriate’s proficiency in the host language. It is worth noting that this factor is particularly relevant for multinationals in which English is not the parent-country language. Although most multinationals mandate the use of English as the corporate language, especially if employees from different national origins interact, in reality a large part of communication occurs in the HQ country language. Inpatriates who are fluent in this language will be able to adjust more quickly to the HQ environment while also better understanding the subtleties of the HQ corporate culture and specific practices and routines. Host language proficiency also helps inpatriates to develop social capital with HQ staff more quickly. Barriers to Inpatriate Success My study also identified three barriers to successful inpatriation. ethnocentrism . As cultural and organizational outsiders to HQ, inpatriates may face biases and negative perceptions among HQ staff. This problem is more relevant for inpatriates than expatriates, given that the former have less status and influence attached to their position. Ethnocentrism refers to the belief that the values and attitudes held in one’s own culture are superior to those embraced by people in other cultures. For example, an Indian inpatriate remembered the frequent doubts that his HQ colleagues voiced concerning the ieseinsight need to employ an inpatriate from abroad rather than tapping homegrown talent, and this made it more difficult for him to provide value to the HQ operation. My study demonstrated that ethnocentric attitudes among HQ staff had a restraining effect for inpatriates. In fact, host ethnocentrism inhibited inpatriates’ ability to build trusting relationships and develop identification with HQ. This, in turn, made it more difficult for inpatriates to engage in knowledge exchanges, and also made it less likely for inpatriates to remain with the company in the long term. cultural distance . Imagine a male inpatriate being transferred from an Indonesian subsidiary to the headquarters of a German multinational to learn HQ routines and practices and to share his knowledge of the Indonesian market. Can we assume this knowledge sharing will take place automatically just by relocating this person from a vastly different cultural environment to HQ? The answer, of course, is no. When communicating across cultures, people transmit words and signals rather than meaning. The greater the cultural differences between the sender and recipient, the more likely the meaning of what is exchanged may be perceived differently, leading to incorrect attributions. The actual exchange of knowledge only occurs if the knowledge sent is correctly interpreted. My argument is thus: The greater the distance between the inpatriate’s home culture and the HQ country culture, the less knowledge exchange actually occurs. Moreover, cultural distance also negatively impacts inpatriates’ ability to build trusting relationships with host colleagues and to identify with HQ, and by extension, reduces the likelihood of inpatriate retention. lack of repatriation and career planning . Out of all the factors measured, inpatriates rated issue 5 second QUARTER 2010 43 the power of GLOBAL Welcoming the Value That Inpatriates Bring THINKING Managing the Inpatriation Process FIGURE 2 CAPITALIZING ON INPATRIATE TRANSFERS REQUIRES THAT MULTINATIONALS HEED THESE CONSIDERATIONS AT EVERY STAGE. SELECTION 1 the existence of repatriation and career planning as the lowest. One returning inpatriate was very vocal about this: “Actual focus is only on the short-term, not on long-term development. There is no career planning – only waiting to see what posiP R E PA R AT I O N 2 tions open up and then dumping returning employees into Provide cross-cultural training them.” for inpatriates and HQ staff Overall, inpatriates seemed Identify suitable HQ mentor happy with their international experiences, though this was 3 due more to the generally posiR E L O C AT I O N tive experience of living abroad Provide ample opportunities than to the way the company for inpatriates to develop managed inpatriate transfers relationships with other and their longer-term career departments or functions prospects. The implications of Provide ongoing development this are clear: If inpatriates do and social activities not consider their employer willing to take care of them, 4 despite having relocated geoR E I N T E G R AT I O N graphically and culturally to Make sure inpatriate transfer often very different environfits into logical career path ments, why then should they Reconcile compensation remain loyal to their employer? systems across units Why shouldn’t they turn around and sell their international experience to another company? Considering that smaller subsidiaries offer fewer opportunities for promotion, longer-term career planning becomes all the more vital. As a Japanese inpatriate remarked, “The Japanese subsidiary is mainly a sales unit, and so, quite small. Before coming to Germany, I had already reached the highest possible level in my company. So what is my motivation to return to Japan with (this company)?” Without a clear and attractive plan of where to go, this inpatriate is unlikely to remain with the company, jeopardizing the investment the company has made in this manager. Prefer candidates with: a) previous international experience b) ease in building social relationships c) host language proficiency 44 second QUARTER 2010 issue 5 Multinationals: Take Hold of the Process Given these challenges, capitalizing on inpatriate transfers requires multinationals to manage inpatriation across every stage of the process (see Figure 2). selection stage . There are implications concerning the criteria that HR managers need to apply for selecting individuals for inpatriate assignments. Whereas many companies only focus on technical expertise, other selection criteria should be considered, too. For example, given the negative influence of cultural distance, it is important to choose individuals who have gained prior international exposure, either through previous international assignments, or as a result of having lived or studied abroad for a substantial period of time. It is likely that these previous cross-cultural experiences reduce inpatriates’ perceived cultural distance. It is also important for HR managers to take into account the quality and scope of potential candidates’ social networks in their home unit. For example, if an individual is able to maintain an extensive social network at home that spans different work groups, departments or even functional areas, this indicates that the person will be more able to build a similar network in a new work context. Finally, candidates with greater host language abilities should be preferred. preparation stage . While much has been written about cross-cultural training for the actual assignee, local staff is often left out of the equation. However, due to the role of host ethnocentrism as an important barrier to inpatriate success, companies will also need to involve HQ staff more explicitly in the inpatriation process and prepare them to interact with inpatriates on an everyday basis. Only if locals understand the value that inpatriates can contribute to the organization will inpatriates be able to receive the necessary credit to build social capital at HQ. In addition, it is important at this preparation stage to search for and identify an appropriate HQ mentor who will be able to accompany the inpatriate upon arrival at HQ. relocation stage . Given the developmental nature of most inpatriate transfers, companies are well advised to provide inpatriates with ample opportunities to get to know and ieseinsight the power of GLOBAL THINKING Welcoming the Value That Inpatriates Bring It is important to change the traditional mindset that views multinationals as HQ-centric organizations whose foreign subsidiaries are dependent. Diversity in staffing provides a broader understanding. develop relationships with different departments and functions at HQ. Having this diverse exposure allows inpatriates to build greater social capital as well as learn and exchange knowledge with a wider range of sources. It is also important for multinationals to offer ongoing development and social activities during the relocation that help inpatriates to develop identification with and become socialized into the HQ corporate culture. reintegration stage . The study also highlights strategic issues arising from the use of inpatriates. Whereas many companies plan and conduct international transfers on an ad hoc basis, such an approach fails to capitalize on the longterm benefits that result from inpatriation. Consequently, HR managers need to embed staff transfers into logical career paths that fit with the long-term goals of both the company and the individual assignee. In addition, inpatriation requires greater integration of the different compensation systems that exist in a multinational. The reintegration of inpatriates to countries with substantially lower market salaries can lead to a huge decrease of salary, a gap that is often more pronounced than in the case of expatriate assignments, and may thus trigger turnover tendencies among returning inpatriates. Above all, it is important to change the traditional mindset that views multinationals as HQ-centric organizations whose foreign subsidiaries are dependent. Adidas, a premier global sporting goods brand, is an exemplary case of overcoming this HQ bias. Its corporate HQ – located in Herzogenaurach, a small town in the south of Germany – is merely one of many company units spread around the globe. People are transferred in all directions, with HQ acting as a provider as well as a recipient of international staff, just like every other unit. HR managers at Adidas concur that it is this diversity in staffing that provides employieseinsight ees with a broader understanding of the overall organization, that offers career opportunities beyond the local context for parent-country as well as foreign employees, and that ultimately enables the company to respond to local differences in tastes and preferences. This is something that every multinational would be well advised to learn from. to know more n n n n n Reiche, B.S. “The Inpatriate Experience in Multinational Corporations: An Exploratory Case Study in Germany.” International Journal of Human Resource Management 17, no. 9 (2006): 1,572-90. Reiche, B.S. “To Quit or Not to Quit: Organizational Determinants of Voluntary Turnover in MNC Subsidiaries in Singapore.” International Journal of Human Resource Management 20, no. 6 (2009): 1,362-80. Reiche, B.S., and A.W. Harzing. “Management of International Staff.” Barcelona: IESE, 2009. Ref. no. DPON-79-E. Reiche, B.S., A.W. Harzing and M.L. Kraimer. “The Role of International Assignees’ Social Capital in Creating Inter-Unit Intellectual Capital: A CrossLevel Model.” Journal of International Business Studies 40, no. 3 (2009): 509-26. Reiche, B.S., M.L. Kraimer and A.W. Harzing. “A Social Capital Perspective of Knowledge Sharing and Career Outcomes of International Assignees.” Best Paper Proceedings of the Academy of Management Annual Meeting, Anaheim, August 8-13, 2008. issue 5 second QUARTER 2010 45