inpatriate managers: how to increase the

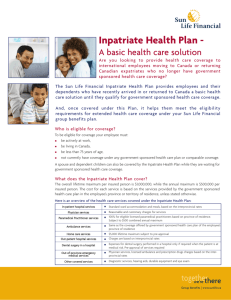

advertisement