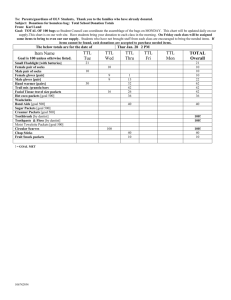

Report of the Mid-program evaluation of 'take the lead'

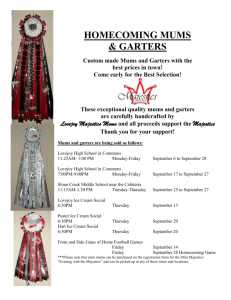

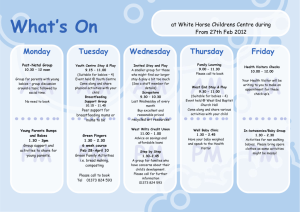

advertisement