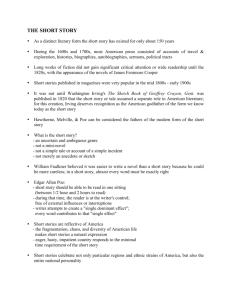

The American Monthly Magazine - oracle

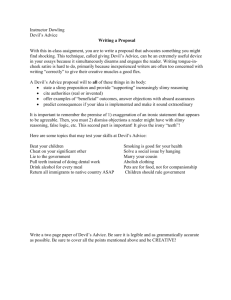

advertisement