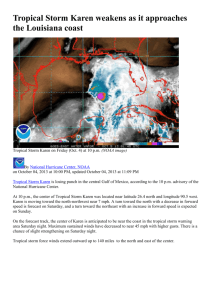

Investigating the Role of the Upper

advertisement