2013/14 Learning from Operational Experience Annual Report

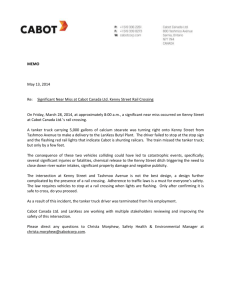

advertisement