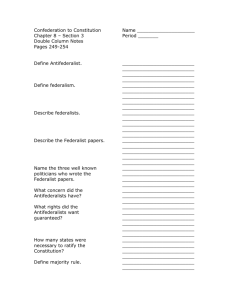

United States Constitution

advertisement