Living Gluten-Free by Tricia Thompson MS, RD, The Gluten

advertisement

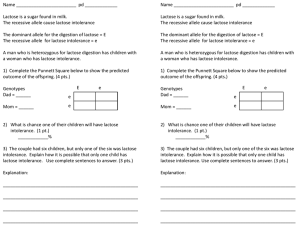

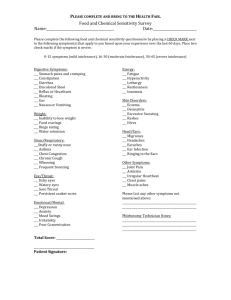

Living Gluten-Free by Tricia Thompson MS, RD, The Gluten-Free Dietitian The Celiac Disease-Lactose Intolerant Connection When they are newly diagnosed with celiac disease, many people also discover that they are lactose intolerant and have difficulty digesting milk and products containing milk. This type of lactose intolerance is called “secondary lactose intolerance.” It is a temporary form that develops as a result of celiac disease and resolves (in most cases) as the intestine heals. Lactose is a sugar found in milk. It is a “disaccharide” meaning it is made up of two units of sugars. “Di” means two and “saccharide” means sugar. Specifically, lactose is made up of one unit of glucose and one unit of galactose. Disaccharides -- including lactose -- cannot be absorbed intact from the small intestine. Instead they must be separated into single units of sugar (monosaccharides). Enzymes that help do this are found in the small intestine. When someone has lactose intolerance, lactose passes undigested through the intestinal tract where it causes symptoms familiar to anyone who suffers from this condition — diarrhea, gas and bloating. But why does lactose intolerance develop in the first place? The lining of the small intestine contains hair-like projections called villi. These villi are lined by cells called enterocytes, and each one of them has smaller hair-like projections called microvilli. These microvilli also are called the “brush border.” Enzymes that help digest sugars (as well as break down products of protein) are found in the brush border and are called “brush border enzymes.” When you have celiac disease, the mucosa (or lining) of your small intestine is damaged. Specifically, the villi become shortened or even completely flattened. This results in a decrease in brush border enzymes. Brush border enzymes include lactase which helps digest the sugar lactose found in milk; sucrase which helps digest the sugar sucrose found in varying amounts in all plant foods, including fruits, vegetables, and sugar cane; and maltase which helps digest the sugar maltose found in cereal grains. Should you also be concerned about sucrose and maltose intolerance? Because the enzymes sucrase and maltase needed to digest sucrose and maltose also are found in the brush border you may be wondering if you might have secondary intolerances to these sugars. I asked Dr. Stefano Guandalini, Director of the University of Chicago Celiac Disease Center, to explain why this probably is not the case. "The enzymes lactase, sucrase and maltase are all found in the brush border. Why is it that lactose intolerance is common among persons with celiac disease but sucrose and maltose intolerance are not? "Among all disaccharidases (lactase, sucrase-isomaltase, and maltase), lactase is the one of lowest abundance in the brush border membrane and is therefore the first to be affected when there is a reduction of the intestinal absorptive area, such as in untreated celiac disease." How often do patients in your practice have secondary sucrose and/or maltose intolerance? "Even though the levels of sucrase-isomaltase and maltase may be reduced if measured in the intestinal biopsies of newly diagnosed patients, this is essentially of no clinical significance, as the remaining enzyme activity is plentiful to reach effective digestion of those sugars. So the honest short answer is: never!" If a patient suspects they may have a secondary intolerance to sucrose and/or maltose what are your recommendations? "Since these intolerances (if at all present) are by definition transient, the most logical option is to substantially reduce the intake of these sugars for a period of time adequate to allow for reconstitution of the normal enzyme activity. This time may be different from person to person, but if the gluten-free diet is strict, I would assume that in the majority of cases a few weeks should be more than sufficient." In general how long does it take for lactose intolerance secondary to celiac disease to resolve? "Lactose intolerance (if present: in many patients, and particularly those who come to the diagnosis with minimal GI symptoms, even lactose can be fully digested) would persist until an adequate intestinal absorptive surface is reconstituted; again, this is variable between different patients, but typically 2-3 months should be enough to allow for regeneration of adequate amounts of lactase. "I would like to add however that a substantial portion of adults present the so-called “adult-type hypolactasia”; a genetically pre-programmed loss of lactase activity that begins sometimes in mid-childhood. In these cases, obviously the intolerance won’t regress. We have today the possibility to test for the existence of this genetic condition via a simple blood test." Thank you Dr. Guandalini! For more information on lactose intolerance, please see the National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse web page on lactose intolerance. Tricia Thompson, M.S., RD is a nutrition consultant, author and speaker specializing in celiac disease and the gluten-free diet. She is the author of The Gluten-Free Nutrition Guide (McGraw-Hill) and co-author of The Complete Idiot’s Guide to GlutenFree Eating (Penguin Group). For more information, visit www.glutenfreedietitian.com. This article was originally posted on diet.com Copyright © 2008-2009 by Tricia Thompson, MS, RD