Coping with Deflation

advertisement

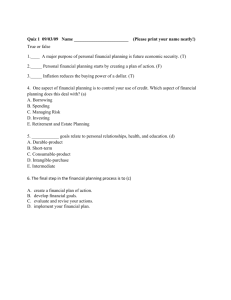

Legislative corner Coping with Deflation The Phantom “Bonus” Many benefit plans (including Social Security) are indexed to inflation, as measured from the third quarter of one year to the next. But only increases, not decreases, are automatic. So when the Consumer Price Index (CPI) declined roughly 2% from 2008 to 2009, Social Security benefits and most every benefit plan limit remained unchanged in 2010. While there was a popular outcry about this, it actually represented a 2% net increase in benefits over the previous year on an inflation-adjusted basis. But what one hand giveth, the other taketh away. These Social Security and other benefits plan “bonuses” will be clawed back because any net gains must be accounted for—i.e., taken out of—future increases due to higher rates of inflation. How this works is relatively simple. Since 2009 the CPI for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W) went down, while benefits remained unchanged for 2010. Any change in benefits for 2011 will be based on CPI-W for 2010 relative to 2008 (not 2009). Thus, it will take roughly a 2% inflation level over the course of the next year to break even. For example, if there is 3% growth in CPI-W from the third quarter 2009 to the third quarter 2010, Social Security benefits for 2011 will increase only by the excess 1%. The longer CPI remains negative (which is to say, deflationary), the longer it will take on the back end to make up for that inflation-adjusted “increase” in unchanged benefits payments. A similar automatic adjustment basis is used for various IRS benefit plan limits, such as the maximum 401(k) contribution. (However, CPI for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) is used instead of CPI-W.) In addition, it’s important to remember that these limits have rounded thresholds that have to be crossed before a change is realized. The chart below shows some key limits and the inflation needed over this year to generate a change. A slightly trickier indexed amount is the Social Security Taxable Wage Base ($106,800 for 2009), which limits wages subject to the 6.2% Social Security portion of the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) tax and moves with changes in national average wages. Because of reporting lags, the most recent wage index is for 2008, but this is used in determining the 2010 taxable wage base. While 2008 shows an increase of 2.3% over 2007, the taxable wage base for 2010 did not increase since there is no cost-of-living adjustment in Social Security benefits for 2010. Thus, the 2010 taxable wage base will continue to be $106,800. For 2011, the taxable wage base increase will be based on the increase in 2009 average wages over 2007 (not 2008, since there was not an adjustment in this year’s wage base). As long as there is any cost-of-living adjustment in Social Security benefits (recall, that means inflation will have to exceed 2%), then the full two years of wage growth between 2007 and 2009 will increase the 2011 taxable wage base. 2009 & 2010 Rounded threshold ($) 2009 Unrounded threshold ($) 2010 Unrounded estimated threshold ($) Next threshold ($) Inflation needed to increase (%) 195,000 197,360 194,156 200,000 3.0 Defined contribution dollar limit 415(c) 49,000 49,340 48,539 50,000 3.0 401(k) deferral limit 402(g) 16,500 16,707 16,436 17,000 3.4 5,500 5,569 5,479 6,000 9.5 Qualified plan compensation limit 401(a)(17) 245,000 246,700 242,695 250,000 3.0 Highly compensated employee threshold 414(q) 110,000 111,472 109,662 115,000 4.9 Key Benefit Plan Limitations Defined benefit dollar limit 415(b) Catch up contribution limit 414(v) Source: J.P. Morgan Compensation and Benefit Strategies 8 JOURN EY Winter 2010 Legislative corner Implicit Impact? Considering longevity risk According to recent J.P. Morgan analysis, the 2008 market decline increased the retirement age for a typical employee by as much as four years. When potential employer actions like a 401(k) match suspension and/or pension plan freeze were added, the retirement age increased by as much as seven years. By considering an analytic framework built around a participant’s determination of retirement supply, demand and optimal retirement, it is possible to establish a preferred distribution strategy. From this framework, we have determined that: A lump sum distribution from a pension plan can increase a participant’s • optimal retirement age by as much as two years (longevity risk significantly increases). 401(k) match suspensions have a relatively small impact on optimal retirement age (less than six months). Failure to incorporate assumptions on assets outside of corporate retirement plans can have a large impact on assessing retirement readiness (availability of outside assets can reduce retirement age by three to four years for a typical employee). Given the large boomer cohort and retirement planning stress of the last 18 months, monitoring employee retirement readiness has become a critical component in corporate talent and succession planning. Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows that over 40 percent of the American workforce will be eligible to retire in the next 10 to 15 years. Arguably, managing the orderly progression of boomer retirements may be the most important task facing HR executives in the next decade. • • IRS final regulations on funding and benefit restrictions In August 2006, Congress passed the Pension Protection Act. In October 2009, over three years later, the IRS finalized regulations, 319 pages worth, on DB funding and benefit restrictions. What’s new? In short, not much. Since the proposed regulations were first released, updated guidance has crept out in various forms. For example, the Worker, Retiree, and Employer Recovery Act of 2008 (WRERA) already settled the asset “averaging vs. smoothing” debate, and an IRS newsletter in late September allowed plans to make a fresh interest rate election for 2010, which meant they could take advantage of the unusually high spot yield curve for 2009 funding. The final regulations formalize such changes, and clarify some other items: The use of a “standing election” to apply credit balances against minimum funding requirements. Allowing sponsors that apply a credit balance to minimum funding requirements and then “over-contribute” for the year to use the excess to replenish their credit balances. Elimination of a requirement in the proposed regulations that plans offer participants the right to defer payment of the restricted portion of a prohibited payment beyond normal retirement age where the plan did not otherwise provide for such a deferral. Clarification of rules for calculating the prohibited portion of an accelerated payment that will allow payment of Social Security level income benefits in many cases. Pension Funding Relief House Rep. Earl Pomeroy (D-ND) continued his efforts to help DB plans weather the financial storm. On October 27, 2009, he and Representative Patrick Tiberi (R-OH) introduced the Preserve Benefits and Jobs Act of 2009 (H.R. 3936). The major provisions of the bill follow closely Rep. Pomeroy’s earlier discussion draft that we summarized in our last edition, including extended amortization of 2008 investment losses, expansion of the “asset smoothing” corridor, and “lookbacks” to 2008 pre-loss funded ratios for benefit restrictions and credit balance purposes. The primary goal of these provisions is to help sponsors save cash by delaying contribution requirements. What’s changed? As before, if a sponsor takes advantage of the extended amortization option, a “maintenance of effort” will be required—e.g., maintain the DB plan or, if it is already frozen, provide a 3% allocation in the DC plan, or freeze all non-qualified benefits. However, the maintenance periods have been cut in half in the bill as introduced. Further, the final bill removed the ability to make a fresh interest rate selection for 2010 since the recently released final IRS regulations now provide that ability. Finally, the new version tightens up the “PBGC 4010” reporting required for underfunded DB plans. J.P. Morgan J O U R NEY 9