PDF Version

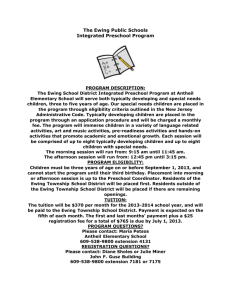

advertisement