F.O.B. yumi janairo roth

advertisement

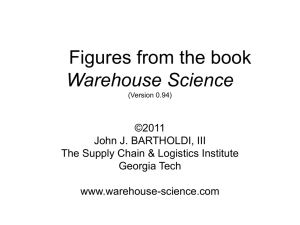

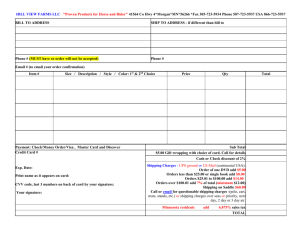

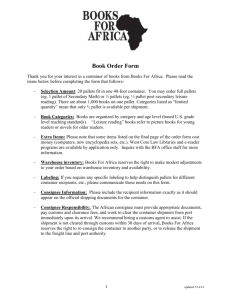

cuchifritos new york, ny F.O.B. yumi janairo roth Essex Street Market photograph by Nadine Wasserman The Essex Street Market and its Origins 1 Suzanne Wasserman, Director, Gotham Center for NYC History In 1930, at the start of the Great Depression, 47,000 New Yorkers depended on earnings made from pushcarts; purchases generated $40 to $50 million each year. More than 50 percent of all the pushcarts in the city were to be found on the Lower East Side. The peddler and his five-cent apples became the ubiquitous folkloric symbol of the economic hardships of the Depression years. For a time, peddling kept unemployed New Yorkers off charity and, later, off relief, both of which many saw as the ultimate humiliation. 2 City merchants did not empathize with the plight of the unemployed; instead, they viewed the increase in peddling as a nuisance. At least a decade earlier, merchants had initiated a campaign to wipe peddling out completely. Their explicit goal was the “establishment of central public market buildings and the abolition of all curb pushcarts.” 3 In the pushcart districts, merchants always considered the carts unfair competition. They assumed, mistakenly as it turned out, that the pushcarts lowered property values and competed unfairly with “legitimate stores.” Peddlers were also a psychological threat. Little more than a front door and a bit of savings separated the merchants from the pushcarts and their practices. Many merchants engaged in the same self-exploitation as the peddlers. They employed their entire families, often lived in the dark backrooms of their store, and worked from 5 A.M. until 11 P.M. The merchants were often less than a step ahead of the peddlers on the rung of “success.” 4 Upon his election to the mayoralty in 1934, Fiorello LaGuardia took up with a vengeance the issue of the public markets. The federal government had poured huge amounts of money directly into New York City with the advent of the New Deal. It aimed to create jobs by promoting municipal improvements. The City Council asked the Board of Estimates to use the city’s WPA funds to create indoor markets. The first indoor market opened on Park Avenue between 111th and 116th streets in 1936. Other indoor markets followed, including the markets on Essex Street, on First Avenue and Tenth Street, and on Arthur Avenue in the Bronx. These new indoor markets housed only a fraction of the peddlers and also charged more. For example, the new Essex Street Market, opened January 10, 1940, housed 570 stalls and charged the peddlers four dollars per week, four times the amount they had previously paid on the streets. Peddlers, still acutely feeling the pangs of the economic Depression, reacted pessimistically to news of the new municipal markets. In 1936, an article in the New York Post entitled, They Might Starve Faster Indoors: Pushcart Dealers Too Depressed to Care, proclaimed that, “Indoors, a pushcart woman exclaimed, the peddlers will ‘just starve faster, 5 that’s all… Nobody buys, nobody’s got the money, everybody’s on relief.’ ‘Inside it will be worse,’ claimed another, ‘but outside it’s so bad you can’t make a living. Some days I don’t make 75 cents. Can you live on that?’” 6 With the creation of the indoor markets, LaGuardia had been able to accomplish what the merchants could not. With the help of the New Deal’s unprecedented aid to cities, through the WPA, LaGuardia achieved his goal in about five years. Peddlers were now “forbidden” to sell merchandise on the streets, and those who could not afford an indoor stand were simply out of luck. 7 One observer at the opening of an indoor market noted that, “the peddlers were attired in neat white coat. Each stood by his indoor stand, his wares in orderly array. LaGuardia launched into his address, and, suddenly, in the middle of it, stooped and picked up an apple from one of the stands. ‘There will be no more of this,’ he said as he pretended to spit on the apple. . . . Pointing to his listeners in their crisp white coats, he concluded, ‘I found you pushcart peddlers…I have made you MERCHANTS!’” 8 LaGuardia praised peddlers like Isadore Suranowitz who had been a peddler on the same corner since 1913. “Tomorrow,” Suranowitz predicted, referring to the opening of the First Avenue market, “You’ll see me in a clean shirt. No more like a peddler, I’ll be a merchant.” Unfortunately, peddlers like fifty three year-old Giuseppe Sallemi would never make the move from peddler to merchant. He made one dollar a day selling lemons and could not possibly afford a stall indoors. Instead, he joined the ranks of the unemployed. 9 The indoor markets opened with rules and reflected LaGuardia’s determination to “professionalize” the peddlers. The rules now explicitly spelled out acceptable and unacceptable codes of behavior. Rule 21, for example, stated that, “permittees or their authorized helpers must remain behind their counters when transacting business and keep aisles free for the use of patrons”; rule 22 declared that the peddlers, “must, at all times, be courteous”; and rule 23 stated there was to be, “no shouting or hawking by vendors nor abusive and lewd language.” An amendment further hardened the administration’s position. Now, all vendors had to be citizens, which cut at the very heart of the peddling community. Ironically by 1940, the business community, which had fought for ten years to remove the embarrassing pushcarts, now complained that their removal had irreparably damaged their trade. Much to their shock, the merchants soon saw that once the pushcarts disappeared, they immediately experienced a drastic decline in trade. By late 1941 the merchants on Orchard Street had found that “the removal of the pushcarts… has reduced gross sales…approximately 60 percent. . . . Streets such as Orchard Street enjoyed an international reputation as ‘The Street of Great Bargains’. . . . The removal of the pushcarts altered conditions considerably.” Fifteen thousand peddlers lined the streets of the city when LaGuardia came to power. By 1945, a little more than ten years later, only twelve hundred still stood. While the campaign taken up by Lower East Side merchants in the 1920s had been stymied, the LaGuardia administration virtually completed it by 1941. 10 11 LaGuardia never succeeded in completely eliminating peddling. Today peddling offers growing numbers of new immigrants a way to earn a living. Battles over issues of peddling abound in many predominantly immigrant neighborhoods. In recent years, debates have swirled around vendors clogging the streets of Harlem, Washington Heights, and the Lower East Side. Questions persist concerning the fate of poor and primarily immigrant people dependent on the marginal economy of peddling, as well as on the place of peddling in the urban environment. Some view the dilemma angrily, others nostalgically, and still others argue that peddling contributes to the vibrancy of city life. The battles over vending remain remarkably familiar and filled with historical ironies. One bright note in recent years is the success of Essex Street Market. Long failing and a blight on the neighborhood, the indoor market is “thriving today as it never did, making available both the world of the bodega and the universe of the gourmand.” New York City’s Economic Development Corporation poured $1.5 million into its renovation. In a city increasing segregated into the very rich and the very poor, the Essex Street Market today ironically stands as an example of a successful commercial space that caters to local residents and visitors alike. 12 1-Based in part on my essay, Hawkers and Gawkers: Peddling and Markets in New York City, Gastropolis: Food and New York City, Annie Hauck Lawson and Jonathan Deutsch (eds), Columbia University Press, 2008. 2-East Side Chamber News, March 1930, p 7 – 8. 3-East Side Chamber News, June, 1929. 4-Albert Henry Aronson, The Ramifications of Our Marketing Problem, ESCN, November 1929, 17; and also see Rebecca Rankin, New York Advancing—World’s Fair Edition (New York: Municipal Reference Library, 1939), 105; Mark Soliterman, The Small Retailer on the East Side, ESCN, December 1929, 17. 5-Harry B. Brainard, City Plans Four Public Market Buildings on Essex Street, ESCN, September 1936, cover. 6-Ruth McKenny, They Might Starve Faster Indoors: Pushcart Peddlers Too Depressed to Care, New York Post, July 11, 1936, sec. 2, 3:3–6. 7-ESCN, December 1937, 8; April 1937, 7; and July 1937, cover. 8-Newbold Morris,Let the Chips Fall: My Battle Against Corruption (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1955), 119-20; and Robert Caro, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (New York: Vintage, 1975), 447. 9-Editorial, New York Herald Tribune, December 1, 1938, 3-5. 10-Editorial, Chamber Director Wins Stoop-Stand License Fight Against License Commissioner, ESCN, October 1941, 4. 11-Rebecca Rankin, ed., New York Advancing—Victory Edition (New York: Municipal Reference Library, 1945), 208; New York Advancing—1939 Edition (New York: Municipal Reference Library, 1939), 105. 12-Ginia Bellafante, A Market Grows on the Lower East Side, New York Times, December 6, 2006, F1 Cargo Cult, found shipping pallets inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 2009 photograph by Derek Eller A conversation between Yumi Janairo Roth and Nadine Wasserman, Independent Curator and Critic The title F.O.B.: Yumi Janairo Roth contains a double meaning. “F.O.B.” not only stands for “freight on board” but it is also a term used to mean “fresh off the boat” in reference to immigrants who have arrived from a foreign nation and have not yet “assimilated.” The Lower East Side, a historically immigrant community, is the perfect setting for the body of work Roth created during her recent residency with the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council. During her residency Roth gathered discarded shipping pallets from her Lower Manhattan environs and intricately inlaid each one by hand with mother-of-pearl using patterns gleaned from traditional Southeast Asian furniture and decorative objects. In this way, Roth re-considers a ubiquitous yet most often disregarded object. Given a second life, the pallets become surrogates for the immigrant experience. They are at once local and global. In much of her work, Roth uses everyday objects as symbols for the ways in which our external environment is controlled and transitory. She calls attention to objects that might otherwise be overlooked but that influence our lives without our taking much notice. For a solo exhibition in Houston she altered various barricades and traffic cones and placed them throughout the city. By adding disco mirrors to wooden traffic barriers, decorative orange and white striped satin slipcovers to concrete Jersey barriers, and piñata decorations to traffic cones, Roth drew attention to objects that were generically unassuming yet authoritarian. Her alterations re-contextualize these objects and subvert their control. By glamming up these otherwise mundane objects, Roth asks questions about comfort, safety, and displacement. Roth’s shipping pallets function in a similar way. They are reimagined as decorative objects. In an earlier iteration, Roth constructed shipping pallets by hand that were highly-polished, inlaid, and finely carved. Her current series are authentic shipping pallets that she has inlaid by hand with mother-of-pearl, but left rough, broken, and stained. They are transformed by ornamentation but they retain their street cred as the workhorses of global shipping and commerce. In a sense they are symbolic of immigrants and guest workers — uprooted, often invisible, yet indispensable to the world market. Most often generic and nondescript, the pallets become representative of the way various ethnicities have inhabited the neighborhood, each bringing to it their own food and culture, often shipped from abroad. The Essex Street Market is a microcosm of the many cultures that inhabit the area. Historically it is the descendent of the once ubiquitous pushcarts that were forced indoors by Mayor LaGuardia. In the context of the Market, an installation of Roth’s pallets along with photographs of the pallets on city streets illuminates the ubiquity and dignity of these once forlorn and subjugated objects. Cargo Cult, found shipping pallet inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 2009 photograph by Yumi Janairo Roth NW: Much of your work is influenced by place. Can you explain your working process and how you develop your ideas? YJR: When I travel to a new location, I usually spend quite a bit of time wandering around, making photographs, and taking notes of situations, objects, etc., that I find unusual or unfamiliar. In fact, I'm often at my most productive when I'm least comfortable in the place where I'm (temporarily) living. The unfamiliarity of everything makes me acutely aware of my surroundings, which in turn gives me ideas about how I might respond to a particular place. Although I might have a rough idea of what I could work on, I need to spend time in a place to fully understand what sort of project I might undertake. NW: You are trained in metals but your work is mostly conceptual and sculptural. Can you explain what influences your choices in terms of materials and subject matter? YJR: In addition to metalsmithing, I also have a background in anthropology and archaeology. As a result I'm extremely interested in the social history and meaning of objects and materials. The academic term for "things" in anthropology is "material culture" and this term best describes how I think about objects and their relationship to social/cultural situations. Essentially "material culture" describes the whole constellation of cultural, social, and economic relationships that objects embody. I think that I'm most drawn to things that are overlooked or considered banal. In past projects, I've worked with police barriers, traffic cones, didactic design, and maps, all things that we encounter and use on a daily basis, but rarely consider beyond their most basic function. NW: How did you start this particular body of work? YJR: This most recent iteration of found shipping pallets inlaid with mother-of-pearl, documentation of the pallets, and diazo print drawings is part of a larger project I started in 2005. At that time, I worked in the Philippines as an artist-inresidence at the Vargas Museum located in Metro Manila. I was interested in looking at "traditional" methods of embellishment, woodcarving and inlay, which were used on a range of kitschy to "fine" objects from trinkety souvenir items to high-end, heirloom-quality furniture and architecture. I built shipping pallets from mahogany and inlaid them with mother-of pearl and also worked with woodcarvers and carpenters to realize a series of custom shipping pallets. In 2007 I returned to the Philippines this time to work at the Ayala Museum. In the US, I built the frames for nearly one dozen furniture dollies, packed them in my luggage and, once in the Philippines, had them caned in rattan. Once I reassembled the dollies, I distributed them to several businesses in Manila (a shipping company, furniture moving company, and museum) to use as they might use a typical furniture dolly. I was interested in understanding how those using the dollies might reconcile two conflicting design languages, one highly functional and another highly decorative which inhabited the same object. In the project at Cuchifritos, I was interested in creating a greater schism between the re- Blueprint Drawing no. 1 (above), Blueprint Drawing no. 3 (left), diazo print, 2009 photographs by Cathy Carver I was interested in creating a greater schism between the refined and culturally-specific embellishment of mother-of-pearl and the roughness of used shipping pallets by using shipping pallets that I scavenged from areas around Lower Manhattan. NW: The process of inlaying is incredibly labor intensive. How did you learn it and how are these pieces different than the one you did that was completely handmade? YJR: I taught myself how to do traditional mother-of-pearl inlay. In many ways, my earlier training in metalsmithing helped me to understand how to capture and reproduce the small details found in various decorative objects. Although I hadn’t ever inlaid metal or wood before, it was analogous to many techniques I already understood. In general, this is how I approach all of my projects. I determine the nature of the thing I want to make and then teach myself the requisite skills. In this project, I think that by using existing shipping pallets, I was able to exploit their abject quality. These were pallets that were one step from the dumpster, repaired too many times to continue to be useful. NW: Cuchifritos is the perfect setting for these particular pieces. We both discovered it separately, but around the same time. I was actually doing a food tour of the area. How did you find it? YJR: For several months between 2008-09, I worked in Lower Manhattan as an artist-in-residence. Before my time with LMCC, I hadn't spent any significant time in that area. However, as I was living and working in the area, I spent a lot of time in Tribeca, the Lower East Side and Chinatown. It was during that residency that I started visiting the Essex Street Market and became intrigued by the idea of a "white cube" gallery located in an indoor food market. The usually silent space of the gallery was continuously disrupted by the noise of the market and the normally segregated activities of food shopping, eating, and art viewing overlapped in a slightly messy way. NW: What are you working on right now? YJR: After my stint with LMCC, I lived in Barcelona for several months in the spring. I was interested in the African immigrants who sold faux designer bags that they displayed on blankets (mantas in Spanish) spread out on the sidewalk throughout the city. In Spain it’s called top manta. I decided to start redesigning the blankets so that they better reflected the aspirational quality of fake Prada, Louis Vuitton and Hermés bags. Subsequently I became interested in exploring democratic methods for producing and distributing luxury designer goods and logos. Recently, I started carving potato stamps with the purpose of making my own Hermés, Louis Vuitton and Prada logos, however poorly. Additionally, although I managed to give myself a repetitive-stress injury after months of inlaying pallets, I’m also trying to devise a way to build a full-scale shipping container that is both carved and inlaid with mother-of-pearl.