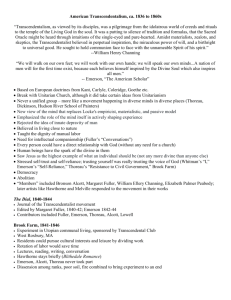

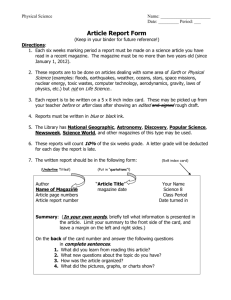

America's Transcendentalist Magazines

advertisement