The Role of Capital Income for Top Incomes Shares in Germany

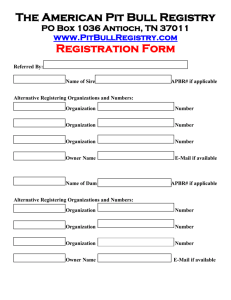

advertisement