The American Felony Murder Rule: Purpose and Effect

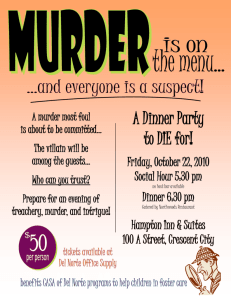

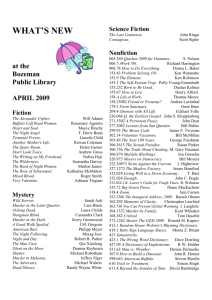

advertisement